A site dedicated to G.K. Chesterton, his friends, and the writers he influenced: Belloc, Baring, Lewis, Tolkien, Dawson, Barfield, Knox, Muggeridge, and others.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

"Lesser" Friend

So, if you want to read a little bit about Ronald Knox, check out Catholic Light's post yesterday. Excerpt:

"On January 16, 1926, [Knox] unintentionally stirred up panic across Britain with his own tongue-in-cheek BBC broadcast. He sent up the conventions of radio news by announcing that a mob in London had stormed the National Gallery, attacked the Houses of Parliament, blown up the Clock Tower, and lynched a minor government minister, all at the instigation of 'Mr. Poppleberry, secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues.'"

Monday, October 30, 2006

Like a Chestertonian Cowboy

It begins with a boy who was never a man and ends with a man who was never a boy.[Jean Westmoore, The Barrie Story is Granted a New Hook. The Buffalo News, 29 Oct 2006]Thus begins the absorbing English-language debut of Argentine-born writer Rodrigo Fresan. This brilliant, ambitious and hypnotically strange novel explores the creation of the Peter Pan legend, the nature of childhood, the nature of memory and of fiction, of growing old and growing up.

...

In an afterword, Fresan reports that he was first inspired to investigate the Barrie story when he saw a film snippet in a French documentary of G.K. Chesterton and Bernard Shaw dressed up as cowboys and playing in a garden with a little man who turned out to be James Matthew Barrie.

I thought this film was lost. This article implies that there may be a portion of it available inside another film. Does any reader know more details of this?

What's been going on

So, that's why posting has been lighter than it should be. That, however, is not what I intend to talk about. Instead, I want to talk about grants.

Grants are the lifeblood of the graduate student universe. They pay tuition, provide for living expenses, pay off student loans and are, on the whole, tremendously wonderful things to be able to cite on one's curriculum vitae. They are a bright and shining beacon that draws other grant-giving entities towards one's rocky shores. If you were good enough for someone else, after all, why shouldn't they give you money, too? It sounds (and is) absurd, in many ways, but it's a fairly straightforward proposition. There's a certain amount of prestige attached to some of these things, and it's only fair that one should profit therefrom.

The two grants with which I am most concerned at the moment are the OGS and the CGS, being the Ontario and Canada Graduate Scholarships, respectively, though the latter is often referred to colloquially as a "shirk," after the acronym of the entity (the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, or SSHRC) that gives 'em out. The former is worth $5,000 a term, for a total of $15,000; the latter slightly more, for a total of $17,500. I'll be looking at about $6,000 in tuition, by way of comparison, so you can see how attractive these things can be. Assuming I'm granted one, I will use it to pay off my tuition, secure a nice place to live, and drop enough off of my student loans that the government offers a buyout option (which they do once you reach a certain amount left to pay). I will then pay that off with money earned through straight work and employment as a teaching assistant, which latter position is generally worth an additional $10,000 a year.

Now, this is all very much chicken counting, for the applications were only submitted within the last few weeks, and, at that, there's no guarantee that I'll even win a grant at all. The decision predictably falls to a series of committees and harried individuals of varying levels of charity, and it will be made largely based on my grades, accomplishments, and proposed course of research. The grades are above average in general, and slightly above the average of those applying for grants, so that's good. The accomplishments stand for themselves, for I have been blessed with a number of awards and the like that have piled up over the last four years, not least of which is the American Chesterton Society's 2005 Gilbert and Frances Award, about which we are always in such a flutter.

These are the tangibles, and things over which I currently have no control. The marks are in, the awards are given out, and that's the end of that. The proposed course of study is the only area in which I myself have any present clout, and it is about this area, naturally, that I am anxious.

Without going into unnecessary detail, I will say that my proposed area of study is Chesterton. Much as I would have liked to simply look at him in and of himself, however, that's not something the government is prepared to give me thousands of dollars to do. Rather I proposed to look at him as a precursor of sorts to various trendy modern theoretical notions like post-colonialism and certain aspects of cultural studies. Seemed convincing enough to the Dean, but it remains to be seen how the committees will react. I am of course hoping for the best, but I'm not holding my breath.

If things progress favourably, you will of course hear more. For the moment, though, that's what has been consuming my days.

Friday, October 27, 2006

"Try one of mine."

R.E. Smith Jr. writes from a pro-capitalism and anti-socialism stance in today's The American Thinker, and he makes extensive use of G.K. Chesterton to support his anti-socialism argument.

I'm reminded of G. K. Chesterton's disdain for collectivists in an essay he wrote in a London socialist weekly, the New Age, in 1908. Chesterton was a prolific English writer well known as a poet, novelist, critic, journalist and essayist. He had no love for modern industrialism, but even less for collectivism. His essay was titled: "Why I Am Not a Socialist."

In a debate with socialists Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Belford Bax, he wrote that he was depressed by the "future happiness" promised by socialist idealism. Chesterton said that most collectivist utopias "consist of the pleasure of sharing." He admitted there is satisfaction in sharing, such as gathering nuts from a tree or visiting a museum. But he preferred the pleasure of giving and receiving.

Giving, he said, is the opposite of sharing. Utopian sharing, he argued, is based on the abhorrent idea that there is no private property.

Chesterton used the analogy of two men sharing a box of cigars. He didn't want that. Rather, he wished that each man might give the other a cigar from his own box. Socialist "eloquence," he said, never recognizes the ideal of "gifts and hospitalities" in its visions of the collectivist state. Their proposals may be appealing, but the "spirit" of their unfulfilled ideals becomes impractical. Ironically, they forget human needs.

G. K. Chesterton put stock in what he called "common people." He believed that individualists promoting industrialism – at that time in Manchester, England – placed an "imposition" on these people (he wrote romantically of simpler, earlier lifestyles). But he also believed that the people, though they may vote for socialists because they want something, detested the "sentiment and general ideal of socialism" as a worse infliction, imposed by "a handful of decorative artists, Oxford dons and journalists.."

[R.E. Smith Jr., Resisting Socialism, Then and Now , The American Thinker, 27 Oct 2006]

"May I smoke?" [asked Syme] "Certainly!" said Gregory, producing a cigar-case. "Try one of mine."

[G.K. Chesterton. The Man Who Was Thursday]

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Fill your soul - buy books!

I am vice president of the Friends of the Gates Public Library. Like Friends organizations across the U.S., we try to help the library in any way we can. One of those ways is raising money to help buy equipment and pay for programs.

Our main source of income in a series of used book sales. We have one tonight, and I will be working at it.

With books on my mind, I naturally thought of “He-who-must-be-quoted.”

And, of course, he had plenty to say on the subject of books.

The opening quote is one I’ve always liked. I know that when I go some place new – including people’s homes – I always check out the books. What they have on their shelves can reveal a lot about them.

A good novel tells us the truth about its hero; but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author. - GKC

I believe we can live without literature – but life is poorer without it

Literature is a luxury; fiction is a necessity. - GKC

For literature is an expression of part of basic human nature.

Truth must necessarily be stranger than fiction, for fiction is the creation of the human mind and therefore congenial to it. - GKC

And it is the old books, the classics which usually offer the richest source of nourishment for the mind and soul.

And all over the world, the old literature, the popular literature, is the same. It consists of very dignified sorrow and very undignified fun. Its sad tales are of broken hearts; its happy tales are of broken heads. – GKC

Despite what the critics say.

By a curious confusion, many modern critics have passed from the proposition that a masterpiece may be unpopular to the other proposition that unless it is unpopular it cannot be a masterpiece. - GKC

So I go to work at the book sale. Go to your own library book sales and support your libraries that way.

Maybe you will help to save a mind, or even a soul!

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Russian Friend

I'm tight for time this morning, so I just offer this interesting snippet:

According to biographer Brian Boyd's recent biography, in 1909 the Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, then a ten-year-old youngster in

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

I am now 12 days away from opening night. Although some of my actors are still having a hard time with their lines, panic has not set in yet. At this point in rehearsal all the blocking, major character development and broad stroke themes are down. This week we begin to polish and begin to get deep in. I work to find the words and phrases that will advance my actor’s thinking to a fuller understanding of the character and the play.

I am now 12 days away from opening night. Although some of my actors are still having a hard time with their lines, panic has not set in yet. At this point in rehearsal all the blocking, major character development and broad stroke themes are down. This week we begin to polish and begin to get deep in. I work to find the words and phrases that will advance my actor’s thinking to a fuller understanding of the character and the play.With my first play, “The Lesson” by Eugene Ionesco, I was delightfully surprised that this help came from the latest issue of Gilbert Magazine. Ionesco’s work is primarily concerned with language and how as a tool for communication it doesn’t live up to it’s marketing claims. To help explain this to my troop I’ve used examples From the Marx Brothers in how language is a great bag for comedy because we really have no idea what we are saying to each other or we only assume we know what the speaker means, (“Last night I shot an elephant in my pajamas. What he was doing in my pajamas I’ll never know.) But Ionesco, a big fan of the Marx Brothers, is not just about the comedy of language he shows us how it can be used to subjugate a people or advance an intrinsically evil agenda or hide one and at the same time letting us think it was a good idea to start with. Bill Cliton’s statement, "It depends on what the meaning of the word 'is' is.” Is pure Ionesco.

The Professor, in Ionesco’s play, claims that language is a scientific thing and “you can tell immediately what language is being spoken simply by listening to the person speaking it”, and “Since language is so difficult it is a wonder the common people can speak at all.” In comes Gilbert Magazine with its GKC’s Essay ‘Allegory’ upfront where he states, “For the truth is that language is not a scientific thing at all, but wholly an artistic thing, a thing invented by hunters, and killers, and such artists long before science was dreamed of. The truth is simply that – that the tongue is most truly an unruly member, as the wise saint has called it; a thing poetic and dangerous, like music or fire. …And It is not merely true that the word itself is, like any other word, arbitrary; that it might as well be “pig” or “parasol”; but it is true that the philosophical meaning of the word, in the conscious mind, that the gusty light of language only falls for a moment on a fragment and that obviously a semi-detached, unfinished fragment of a certain definite pattern on the dark tapestries of reality.” Or as the Maid says in the play “Philology leads to calamity.”

When I first began this adventure I wanted to do a Chesterton play. He was rejected by “the committee” basically on the grounds that he was a Catholic apologist and we did a C. S. Lewis play last year -after all. No, they never read the play I submitted it was rejected solely on the fact that Chesterton’s name was on the cover. So for my second play I came in through the back door of apologetics and submitted J. P. Sartre’s "No Exit". In Peter Kreeft ‘s Essay The Pillars of Unbelief—Sartre (an essay I gave to my cast) he states,

“Jean-Paul Sartre may be the most famous atheist of the 20th century. As such, he qualifies for anyone's short list of "pillars of unbelief." Yet he may have done more to drive fence-sitters toward the faith than most Christian apologists. For Sartre has made atheism such a demanding, almost unendurable, experience that few can bear it.

Comfortable atheists who read him become uncomfortable atheists, and uncomfortable atheism is a giant step closer to God. In his own words, "Existentialism is nothing else than an attempt to draw all the consequences of a coherent atheistic position." For this we should be grateful to him.”

He then goes on to say, “Sartre's most famous play, "No Exit," puts three dead people in a room and watches them make hell for each other simply by playing God to each other—not in the sense of exerting external power over each other but simply by knowing each other as objects. The shocking lesson of the play is that "hell is other people."

It takes a profound mind to say something as profoundly false as that. In truth, hell is precisely the absence of other people, human and divine. Hell is total loneliness. Heaven is other people, because heaven is where God is, and God is Trinity. God is love, God is "other persons."

Now if only they could get their lines down.

the 'My President is Dale Ahlquist' bumper sticker

Get your very own 'My President is Dale Ahlquist' bumper sticker here:

http://www.cafepress.com/kingsland

All proceeds ($2 per sticker) will be forwarded to the American Chesterton Society.

How To Infiltrate Terrorist Groups

[George] Soros blames America for "this clash of civilizations" between the West and radical Islam because "we were basically the dominant power in the world" and so "no terrorist attack could . . . really endanger us."Instead of waging a war on terror, Soros says, we should read G.K. Chesterton's 1907 fantasy thriller "The Man Who Was Thursday" and learn to infiltrate terrorist groups. According to Soros, that's how the British defeated the IRA.

"We have to renounce, repudiate the war on terror," he said, but quickly added: "We have to defend ourselves against terrorists. We have to protect ourselves. But we mustn't make it the be-all and end-all of our policy."

Monday, October 23, 2006

"a book to light fires in my mind"

[T]here are 71 essays to savor in "The Book That Changed My Life," a compilation edited by Roxanne J. Coady...(Carole Goldberg. Reading Tips From Those Who Know Best , The Hartford Courant, 22 Oct 2006)

Coady says she particularly liked the way mystery writer Anne Perry begins her essay:"A good book changes you even if it is only to add a little to the furniture of your mind. It will make you laugh and perhaps cry; it should usually make you think ... For me, G.K. Chesterton's 'The Man Who Was Thursday' is a book to light fires in my mind, uplift my heart, tell me truths I had only glimpsed before."

Busy, as usual

Apologies, as always, are offered. Thank you for your patience, and see you shortly.

Sunday, October 22, 2006

I like the blogs of Dawn Eden mostly because she is one of the strong front line soldiers in spiritual warfare. She is also a fan of GKC, check out this October 13 entry “He's a Rebel”

Friday, October 20, 2006

Payday

My local parish is doing a "Stewardship as a Way of Life" campaign. Although factually true, I believe that slogans like this are just that......more slogans competing for consumer dollars in the marketplace. These drives leave me with a bad taste in my mouth, they are really nothing more than attempts to change some numbers in the check book with the idea of sending some more to the Church.

The writings of the Distributists are what eventually took the bad taste away. The distributist outlook seamlessly blends human dignity, work, ownership, art/culture, and even sexuality and liturgy into a (somewhat) coherent form that you can work to implement into your life.

The Gospel counsels of poverty and possessions are challenging in all times and places. We suffer from the fact of being far removed from Semetic culture to truly grasp the nuances and power of the original meanings of those words. This misfortune is multiplied by the fact that those most interested in economic justice are almost universally marxists in their orientation.........Especially within the Churches.

I consider myself to be a Distributist on a 5-year plan. :-) I work in finance, invest a bit, and study a great deal the workings of trade and wealth generation. The more I study distributism, the more I believe that there are economic forms of pornograpy, adultery, disloyalty, and all the other vices. There is the old maxim, "Be the change you want to see in the world." I truly believe this, and it is an achievable goal. I think to truly live as a distributist, one should be willing to forego certain things, but I can see the rewards in living a truly just life, and truly living in touch with one's humanity.

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Christmas in October

After church on Sunday, I went into a local supermarket to get some things.

That’s when I spotted the Christmas section.

Christmas? On October 15??

We haven’t even gotten past Halloween yet. What’s next: Easter candy before Thanksgiving?

I'm a big fan of Christmas – I have Santa figures and pictures up year round in my house, I've been known to burst into Christmas songs on hot summer days, and I even "help" Santa at a local mall each year (if you’ve even seen my picture, you’d have a clue how!), but this was too much.

My view was that we should get Halloween out of the way, and have at least a little time to think about Thanksgiving before we have to deal with Christmas.

I mentioned my dismay to some folks, and someone told he later went to the store and saw a sign. I hadn't seen a sign when I was there on Sunday, so I stopped in on the way home form work.

Sure enough, there was a sign propped in front of a fake Christmas tree.

Some folks may "like to do their holiday shopping early," but setting up a section like this before even the middle of October is crass.

I went to the desk to register a complaint. I asked for the manager - not there - or the assistant manager - ditto - so the clerk offered to get the night manager. I said no, but asked the clerk to relay the message that I though it was obscene to have the Christmas stuff out this early.

The clerk agreed with my opinion (!), and said mine was not the first complaint.

I’ll bet.

Whoever in the store’s hierarchy made this decision deserves a lump of coal in his or her stocking this year.

I'll wait until December to see if another local supermarket has any coal for sale.

Chesterton had his own solution in “Christmas” when it came to publications jumping on Christmas too early:

"… it is essential that there should be a quite clear black line between it and the time going before. And all the old wholesome customs in connection with Christmas were to the effect that one should not touch or see or know or speak of something before the actual coming of Christmas Day. Thus, for instance, children were never given their presents until the actual coming of the appointed hour. The presents were kept tied up in brown-paper parcels, out of which an arm of a doll or the leg of a donkey sometimes accidentally stuck. I wish this principle were adopted in respect of modern Christmas ceremonies and publications. Especially it ought to be observed in connection with what are called the Christmas numbers of magazines. The editors of the magazines bring out their Christmas numbers so long before the time that the reader is more likely to be still lamenting for the turkey of last year than to have seriously settled down to a solid anticipation of the turkey which is to come. Christmas numbers of magazines ought to be tied up in brown paper and kept for Christmas Day. On consideration, I should favour the editors being tied up in brown paper. Whether the leg or arm of an editor should ever be allowed to protrude I leave to individual choice."

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Wednesday Blues

So what do I have today? Only this: An ongoing series of posts at Love2Learn. The subject? GKC's The Everlasting Man. The approach? Chapter summaries and important excerpts. It's pretty good.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

My President...

I do hope that you will write a nice fat (and valid) check to the ACS. But here is a very little thing that you can also do. It is endorsed neither by Dale Ahlquist, nor by the ACS. I asked permission of no person; viz., you are the first person to find out about this new idea to channel funds to the American Chesterton Society. It is a bumper sticker reminiscent of Clinton-era NRA propaganda... but this is more joyful and universally consumable.

The bumper sticker is made available by me through Cafepress. The cost is $4.99. $2 is the profit on each sticker; all profits will be forwarded to the American Chesterton Society. The recent letter from Dale states a need for $20,000 dollars ... and soon. This Chesterton and Friends blog typically gets around 75 unique visitors daily. What this means to you is that each visitor only needs to buy 134 bumper stickers in order to meet the fund raising goal.

But spread the word and your share of bumper stickers will be lowered!

(If you ask "Who is Dale Ahlquist?" then you can find out here.)

"he does the stories and I do his letters"

"THE USES OF DIVERSITY" by G.K. Chesterton (1920)

This book includes a loosely inserted signed autograph letter from Chesterton's Wife

"Dear Mr. Anderson,

You must forgive me if I write a line instead of my Husband. He is so appallingly busy that he cannot answer half the jolly letters he gets including those from schoolboys. Perhaps you will be pleased to know he has just finished a most thrilling kind of detective story longer than the Father Brown ones which ought to appear shortly, though it is due in America first. You see it is impossible to write stories and answer letters so he does the stories and I do his letters. Here is a copy ... etc etc.

Yours Sincerely,

Frances Chesterton"

available via AbeBooks.com for $51.76 (USD)

GKC on Hymns . . . Kind of

I'm not sure Chesterton's quote fits Blosser's point, but he makes a good one: Catholic hymns are stuck in the Kumbaya movement of the 1970s, when everything about the Church was heading toward relaxed sexual mores and (with a little help from its friends) world socialism. I often bring religious books with me to Church to read during the singing. Is that a sin? I don't know, but the sin was committed before it got to me in those horrible hymn books. I'm more worried about setting a bad example for my children, so I occasionally belt out a hymn or two, when they manage to play a good one. Some day, liturgists in America will realize that saccharine and reverence aren't the same thing. Until then, I'm afraid we're stuck with the junk that is American Catholic movement, circa 1974.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Gilbert comments on "church shopping"

"As usual, G.K.Chesterton summed it up. He said he knew the Catholic Church was for him because when he left his umbrella at the back of the Methodist Church it was still there, but when he left it at the back of the Catholic Church it was stolen."

A Sort-of Chestertonian Crosses the Bosphorus

Beliefnet's Rod Dreher, best known as a chief proponent of the "crunchy conservative" lifestyle - sort of a nouveau distributism - and author of a book thereabout, recently revealed that he and his family have left the Roman Catholic Church and joined that of the Orthodox. The decision was no doubt a trying one, and I hope you will joing me in praying for them.

That said, however, it is a conflicted thing. To read his account is to be plunged into a tale of depravity, heartbreak and betrayal, scandalized beyond innocence and wounded beyond measure. There is something rotten in the American Catholic church, and the stench of it drove this man away.

At the same time, however, it need not have. There is a tendency even among devout religious people - perhaps due to habit, or because they simply aren't thinking clearly, or even, alas, have never really thought about the issue at all - to look at the Church in purely secular, materialistic and consequential terms. It's the sort of thinking that sees an atheist argue with a Catholic about the Church's worth, and the best the former can do is cite the Inquisition, while the best the latter can do is cite the Church's charitable works. Here is a truth that even atheists and anti-Catholics must consider and embrace:

The Catholic Church is not a political party.

We can not simply say, "her rule is insensitive," or, "her leaders are lacking," or, "she does not grasp economics." It is utterly fruitless to discuss the Church in a manner that is divorced from the claims that she makes about herself, whether those claims are true or not. To do so is, at best, to be entirely ignorant of the Church's motivations. In situations such as those that Rod describes, in fact, it is of paramount importance to consider this, and to his credit he recognizes as much even if he does not, it would seem, accept it in the end. Does it shatter the legitimacy of your nation's laws when men break them? When Smith murders Harris does it mean that America (for example) need never have been? The answer to this is clearly no, no matter how gruesome and appalling the death of Harris may be, and yet it is the mad answer of "yes" that keeps so many out of the Church, and drives so many who are already within her mighty bulk away.

Christ promised that the gates of Hell would never prevail against His Church, and it is up to the Catholic faithful everywhere to take Him at his word. This invincibility, however, does not mean that the Church will never know hardship or tremors, and nor does it mean that she is simply mystically preserved from downfall. It is my own opinion (as a wretched layman and general nub) that the Lord's promise on this score was not only a matter of His own supremacy, but also, perhaps, a vote of confidence in the believers who would take up His banner in the days to come.

If this is the case, then, it is unseemly to abandon the Church in her hour of need. If the gates of Hell are not to prevail, then she needs constant shoring up, attention and renewal. She needs to fight for her position, and the faithful need to fight with her. The Church is the bride of Christ, and He didn't marry no wimp.

In the end, however, Rod's reasons for doing what he did do not matter as much as they could, for it is the general opinion of many that he will find similar problems among the Orthodox, for all their gaily-clad solemnity, and will thereafter be faced with quite a problem indeed. Indeed, Rod himself admits to this very fact, yet hopes to "get it right" nonetheless. It is our hope that he will come back, if he feels betrayed again, but it's not going to be pretty when it happens.

The key passage from his explanation, for our purposes, is this:

We kept going back [to the Orthodox parish], and finally got invited to dinner at the archbishop's house. I feared it would be a stiff, formal affair. I was astonished to turn up at the address given, to find that it was the shabby little cottage behind the cathedral. We went in, and it was like being at a family reunion. Vladika's house was jammed with parishioners celebrating a feast day with ... a feast. There was Archbishop Dmitri in the middle of it all, looking like a grandfatherly Gandalf. I had never in all my years as a Catholic been around people who felt that way about their bishop. The whole thing was dizzying -- the fellowship, the prayerfulness, the feeling of family. I hadn't realized how starved I was for a church community. Julie, who grew up Evangelical, said this was what she had known all through her youth -- and what she'd left to become Catholic. I remember thinking that night, given what we'd been experiencing in the liturgy, and now at this parish feast, This is what I thought Catholicism would be like when I came in. And I reflected that there's really no reason at all Catholicism can't be like this. It's not like the Orthodox have some exclusive magic. But there you are.This concerns us for two reasons, and by concerns I mean "matters" rather than "worries." First, this really is what it should be like, both from a Catholic standpoint and that of a mere Chestertonian. Men may differ on just what "life" and "lively" mean, but it must be agreed upon that if the Church must be one thing, it is intensely alive. The family is the seat of all life, and, as luck and prudence would have it, the Church is structured like a family in the efficient, exalted, traditional sense. We have paternal headship, we have feminine grace, and we have quite a brood of children indeed. This is not a resemblence that may be brushed off as coincidental or far-fetched.

Second, this passage underscores the issue of charity in matters such as these. Many have criticized Rod's conversion as being unnecessarily Rod-centric, and it is indeed possible that one may get this impression by reading passages such as that above. His needs weren't being met; his conception of liveliness wasn't being lived up to; his spirit didn't feel on fire for God. These are things that are meant to matter, however, else we would not have been created individuals. What's more, it is no prideful thing to complain that one is "starved for a church community." Yes, we may be petulant: Blah, blah, blah, Rod's not satisfied, etc. But we must, moreover, be gravely worried: There is no church community. This is not something that may be brushed off lightly. It is not enough to turn one protestant, of course, as so often happens, but it should be enough to put the fighting spirit into a body, as the chips are most certainly down. The real infamy of Rod's conversion, if any can be found, is in the fact that he could follow up the statement, "there's really no reason at all Catholicism can't be like this" with the news that he's giving up.

I will close, anyhow, by reiterating my call for prayers, and wishing him good fortune as he goes forth on this curious adventure.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner practically invented the concept of the annotated classic in 1960, with his first Carrollian labor of love, "The Annotated Alice." As versatile as Carroll and now in his 90s, Gardner has written or edited more than 100 books and has been an institution at magazines including Scientific American and Humpty Dumpty's. His "Ambidextrous Universe," about nature's mirror imagery in physics and biology, is a textbook of lucid science writing. With his midcentury collection "Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science," he launched the modern skeptical movement. Gardner's many annotated volumes include G.K. Chesterton's Father Brown stories, Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" and even "Casey at the Bat."Michael Sims. If you're feeling uffish, Los Angeles Times, 15 Oct 2006

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Chesterbelloc

ChesterBelloc

By Ralph McInerny

Chesterton died relatively young, with his authorial boots on, whereas Belloc lived on to enormous old age. There are several evocations of him in the diaries of Evelyn Waugh. "He has grown a splendid white beard and in his cloak, which with his hat he wore indoors and always, he seemed an archimandrite." But the great man had become garrulous and obsessed. "He talked incessantly, proclaiming with great clarity the grievances of forty years ago." That was in 1945. Some seven years later, there is this. "Enter old man, shaggy white beard, black clothes garnished with food and tobacco. Thinner than I last saw him, with benevolent gleam. Like an old peasant or fisherman in French film. We went to greet him at door. Smell like fox. He kissed Laura's hand, bowed to me saying, 'I am pleased to make your acquaintance, sir.'"

Old age, Charles de Gaulle was to say, is a shipwreck. In these lines of Waugh we certainly see the captain of the Nona beached and bewildered in a present in which he only fitfully lived. Somehow they seem a not altogether inappropriate coda to the years of ferocious literary activity. That had ceased now but it was Belloc's achievement as a writer--among other things--that elicited the admiration and piety of Waugh. Visits to Belloc were a duty that sat lightly on the younger writer. He attended the great man's funeral and chided Diana Cooper for wanting to stay away. "The chief reason, of course, for attending funerals is to pray for the soul of the dead friend. The other reason is courtesy to the surviving relations..."

We have been spared the sight of Chesterton grown senile and a bore, but of course that would not have affected our estimate of his achievement. No more do these glimpses of a shuffling old man detract from the enormous achievement of Hilaire Belloc. The two men were linked, by themselves and others, and fused into the Chesterbelloc. Perhaps the most charming examples of their collaboration is to be found in those novels of Belloc that were illustrated by Chesterton. One thinks of the portrait by Gunn in which Chesterton is seated at a table, drawing, with Belloc to his left, looking on, and behind the two, egg bald and somewhat aloof, Maurice Baring. Maybe Baring seems a little embarrassed to be there when the two seated giants are so visibly enjoying themselves.

There are three common notes characteristic of Gilbert Keith Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. First, there is their fecundity, the seemingly ceaseless flow of words from their pens. Second, is the variety of their literary products. Third, is the Christian vision that was as natural to them as the air they breathed.

There is a sense in which it does not matter whether an artist produces much or little: the quality of his opus is the salient thing. Mere quantity is neutral in the sense that some artists produce a very great deal and it is only mediocre or bad, whereas others labor over one or two works which achieve perfection. Obviously it is large amounts of good stuff that one means when he invokes fecundity as a mark of greatness.

It will of course be said that neither Belloc nor Chesterton had time to agonize over any particular work. They wrote under financial pressure or to make deadlines and had to get the thing done. That makes the high quality of most of their work all the more impressive. But it is the sheer fun the two seemed to have had in doing most of what they did that characterizes them. Try and imagine either Belloc or Chesterton with writer's block or talking about the agony of creation. They did not have time for the mannerisms of the second-rate. Analogously, Chester ton remarked about art school that there seemed to be far more artists than people who produced art.

It would be inaccurate to portray Chesterton as a failed artist though the career he eventually had was scarcely the normal outcome of an art school education. The fact is that he became an artist in a minor sense at least. He had a sure hand and the illustrations already mentioned exhibit a visual imagination of great variety. The faces are all clearly by the same artist but no two are alike. There is a clear family resemblance to the figures Chesterton painted for his puppet theater when he was a boy. Belloc on the other hand had aspired to be a don, for years hoping for election as a fellow of an Oxford College. That did not happen and this failure bothered him for many years. Had he won the sinecure of an Oxford fellowship he would have been able to write in a more leisurely and academically acceptable fashion. That was his claim. But surely from time to time it must have occurred to Belloc that failure to become an Oxford don was one of the best things that ever happened to him. As a member of Parliament he came to despise the company he had to keep. It is doubtful that he would have found prolonged proximity to the dons he excoriated in his poetic defense of Chesterton any more palatable. In their different ways, Belloc and Chesterton became free lances, fighting battles of their own choosing on multiple terrains. There was no job description for either man that preceded his endeavors. Ubi vult spirat.

Chesterton said that the world of Charles Dickens was the best of all impossible worlds, and something similar is often thought of his. After all, he was an optimist, he wrote a rollicking prose that often runs away from sense to become a music that mystifies and delights. He can seem so innocent, almost prelapsarian. I suspect that this is one of his greatest accomplishments.

Because it was an accomplishment. Chesterton was not born Chesterton, nor was his future persona thrust upon him. The choice he made was between being Chesterton or going mad. What would going mad have been like? He was attracted to the sensuous decadence of Swinburne. There is a point in his young manhood of which he wrote almost allegorically when he turned from darkness and evil toward the light.

The chapter in his autobiography called "How to be a Lunatic" covers the years during which he studied art at the Slade School in London and became enthralled with spiritualism and the Ouija board. In the period of despair through which he went, Chesterston dabbled in diabolism; later he came to think that he was one of the few who did who really believed in devils. His emergence from this slough of despond is what made him seem an optimist. "Anything was magnificent as compared with nothing. Even if the very daylight were a dream, it was a day-dream; it was not a nightmare." What remained to him of religion was the "one thin thread of thanks." Wonder. Gratitude. Wonder, it has been said, is the origin both of philosophy and of poetry. It turned Chesterton into an exuberant poetic philosopher of gratitude. To see being against the background of nothingness is to see it as created.

Second, there is the variety of their output. Poems serious and comic, novels, book length essays, monographs, collections of essays, memoirs, literary criticism, biography, apologetics, political philosophy, economics--these are genres in which both men wrote. Chesterton even tried history in A Short History of England and it can be said without too much stretching that Belloc wrote detective fiction. To say that the two men overlapped may seem a pun, but they did, even where they seemed most to differ. But if we consider only the kinds that both wrote lots of it is striking. Their poetry deserves more attention than it has received, though it has not been overlooked. Garry Wills some years ago wrote a marvelous essay on Chesterton's poetic works. Belloc's verse for children has been so popular that his other verse is almost eclipsed by it. But Tarantella, to which Marvin O'Connell alludes in his piece, is a hauntingly beautiful poem, intricate in its prosody, sustained in its music.

Third, there is the Catholic outlook that defines the bulk of the work of these two men. In this post-conciliar time when Catholics are alleged to have moved out of the ghetto so as to address the modern world with renewed confidence, the apologetic voice is all but silent. More seriously still, there seems to be missing the robust confidence that the faith is an inestimable gift. Where is the unambiguous assumption that the Roman Catholic Church is the fullness of Christianity and that the faith is the best thing that ever happened to the human race? Belloc and Chesterton were ferocious Catholics, unequivocal Catholics, confessing Catholics, labeled and known to be such. This was the source of their catholicity, not an obstacle to it.

Were ever two thinkers less denominational and sectarian? Neither man thought of the faith as one option among many. It was for everyone. Their missionary zeal was based on the realization that they did not own Christianity; they knew that there are only brethren and separated brethren. It is in very small degree the defects of those in the Church that explain that separation. Men and women have been seduced by the siren song of modernity, to which the faith is an antidote. Try to imagine either Belloc or Chesterton suggesting that, while modernity is a great thing and enjoying success after success, nonetheless we ought to turn back to the Middle Ages and to a discredited view of things. It can't be done. Yet how often this seems to be the choice believers pose to their contemporaries.

The odd contemporaneity of these two men lies above all in their faith. It is our shared faith that makes what they say seem inevitable even when no one else ever said it half so well. C. S. Lewis said of his return to the faith that it put him in possession of the outlook of the writers whose works it was his task to teach. A bonus. There is more than this in the case of Belloc and Chesterton. They enable us to recover gratitude for the faith and wonder at its possession. Not only do we see the role it played in their own efforts. We begin to see the role it should play in ours. All the time. Exuberantly.

(This article originally appeared in the May/June 1998 issue of Catholic Dossier magazine.)

A GKC word search

H C F E L C O L L E B D T K O

L V O I K S D U I T A L B M R

S W C L Q E Q R H Z O E S E T

C E K H L O I U P X A I B R H

C H E S T E R T O N T F E I O

E C R Z T S B M H U B S R A D

B G F I D R C R B J B N N L O

L V R A S N E I E J V O A I X

O Y Y O A T R B L T A C R H Y

G U X B E T M F L Q S A D B G

G T B B S G O A M I I E G S N

W E H I R E L C S L G B H L I

O B D M F R A N C E S A C C R

X O N K R D P F H I W W Z L A

B R O W N X N L D R R Q T U B

BARING

BEACONSFIELD

BELLOC

BERNARD

BLOGG

BROWN

CECIL

CHESTERBELLOC

CHESTERTON

CHRISTMAS

CLERIHEW

DISTRIBUTISM

FRANCES

GEORGE

GILBERT

HILAIRE

KEITH

KNOX

MCNABB

ORTHODOXY

SHAW

THURSDAY

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Lukewarm Soul

Can a reader point out the source of this quote?

New GKC Book

"Stephen R. L. Clark, a philosopher with a lifelong 'addiction' to science fiction and 'an equally long admiration of G. K. Chesterton’s writings,' explores the early twentieth - century scholar’s ideas and arguments in their historical context and evaluates them philosophically. He addresses Chesterton’s sense that the way things are is not how they must have been or need be in the future and his willingness to face up to the apparent effects of the nihilism he detected in much contemporary science and politics."

Press release.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

GKC and Wine

Catholics traditionally love wine. It’s the centerpiece of their liturgy on Sunday mornings and, often, the centerpiece of their dinners on Saturday nights. A Catholic editor once told me, “All good Catholics drink.” He spoke those words at lunch, while drinking Pepsi, so it was no drunken bombast.

He meant it, though I think it’s fairer to say, “A lot of great Catholics have loved wine.”

Read about the early 20th-century Catholic literary revival that biographer Joseph Pearce has chronicled so well. The wine flowed freely — so freely that you might think it was the fuel of the revival. G.K. Chesterton drank it, Maurice Baring balanced glasses of it on his bald head, Hilaire Belloc practically drank a barrel of it during a walking pilgrimage that he recounts in The Path to Rome.

Chesterton and Belloc loved the stuff so much that contemporaries claimed that they had misheard the Creed and thought it demanded belief in “One, Holy, Catholic, and Alcoholic Church.”

Speaking of red stuff. Joe's blog features this GKC quote today: "Red is the most joyful and dreadful thing in the physical universe; it is the fiercest note, it is the highest light, it is the place where the walls of this world of ours wear thinnest and something beyond burns through. It glows in the blood which sustains and in the fire which destroys us, in the roses of our romance and in the awful cup of our religion. It stands for all passionate happiness, as in faith or in first love."

Monday, October 09, 2006

Thomas Bertram Costain

Born in Brantford, Ontario in 1885, Costain would eventually become one of Canada's most delightful novelists and historians, producing dozens of excellent books. He was the editor of the city of Guelph's newspaper at the age of 23, and the editor of Maclean's at the age of 30. He only began his career as a literary writer, however, after moving to the United States to become the editor of the Saturday Evening Post. His first book, For My Great Folly, was published in 1942; he was 57. He died in 1965 (the anniversary of that death was yesterday, in fact), and is, like our beloved Gilbert, largely forgotten today. In addition to his novels, which could conceivably be "ignored" on the grounds of merely being fiction, he also produced invaluable popular histories on all manner of subjects, such as William the Conqueror and a well-received series about the Plantagenets.

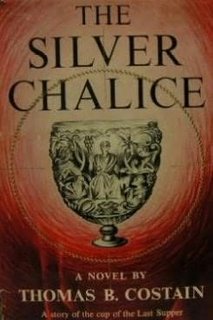

Two of his books concern me here, however, for they are my very favourites of his considerable body of work, and they are certainly both pleasing and accessible to the sort of people likely to be reading this. The two in question were written two years apart from each other: Son of a Hundred Kings in 1950, and The Silver Chalice in 1952.

Son of a Hundred Kings is the remarkable story of one Ludar Prentice, a mysterious child who arrives in Canada, from England, with a hopeful message scrawled across the back of his jacket and no idea where he's supposed to go, or from whence he has come. The man to whom he was supposed to be travelling took his own life on the eve of Ludar's arrival, and he finds himself in a small town of Balfour, Ontario with no past, no future, and something of an odd present. He is taken in by a kindly carpenter named Billy Christian (Costain is occasionally heavy-handed in this way), and the mystery of his past is slowly unravelled. I first read this book while I was down with the flu, and even now I can remember how warm and happy it made me feel. It is not without sadness and villainy, but there is something tremendously cheering about it that burns through. Costain's style is, in contrast to Chesterton's, rather direct and to the point; "unadorned," one might call it. He is certainly capable of delightful linguistic flourishes and edifying digressions, but he keeps them to a minimum.

A more solemn and substantial work, however, may be found in The Silver Chalice, a book that has vied with Tales of the Zombie for my ever-diminishing leisure reading time. A more cynical man might say something observant at this point about the contrast in subject matter, but luckily for us there are no cynics around. I fear I digress, however. The Silver Chalice is a story of the Holy Grail, put simply, but in a more complex sense it's about lots of other stuff too. Basil is a young Greek artist, cruelly deprived of his rightful inheritance by Linus, the brother of his late adoptive father, Ignatius (but not the Ignatius) of Antioch. He eventually comes under the employ of Joseph of Arimethea, tasked with the creation of a glorious receptacle for the cup from the Last Supper, safely hidden away in Joseph's mansion for many years. Basil must travel the length and breadth of the Holy Land - even as far as Rome - to capture perfect likenesses of the Apostles for inclusion in the work. Along the way, he must engage in a spiritual awakening if he is to finally see the face of Jesus in his mind's eye, as His disciples do. The story takes place just after the Ascension, and I think I do not spoil anything by saying that the capture of Paul by the Romans is a pivotal event in the first half of the book.

It is in The Silver Chalice that Costain's craft shines through most beautifully. Everything is plainly and beautifully described; characters are well-drawn but not overdrawn. Much is said about one man or another by the way he stoops his shoulders or taps the bridge of his nose, and Basil's attempts to capture the likenesses of those he meets in clay proves to be a surprisingly effective vehicle for exposing their personalities. And, what's more, I am happy to say that the way in which Costain describes and "writes" the Great Men is nothing short of magical. Here is Luke:

"He had a broad brow and a kindly eye and a smile of such gentleness that each strand of his great red beard seemed to curl in amiability. He was watching, familiarizing himself no doubt with the new faces in the gathering. [His face] was still clear in [Basil's] mind even when the contour of his own father's features had become dim and uncertain. What made it stay was a hint there of seeing things which other eyes missed, of hearing sounds, perhaps of music, in the stillest air."Here is Paul:

"The first close glimpse that Basil was thus afforded of this remarkable man was in the nature of a shock. He was surprised to find how old the great apostle had become. Paul's hair and beard were white, and there were both fatigue and suffering in the lines clustering about his eyes and accenting the hollowness of his cheeks. It surprised the youth also that the face that had been turned to him was not an agreeable one. The features seemed to have been cut out of the hardest granite, and the expression was stern. But at the same time he realized it was a compelling face. The eyes under straight white brows were the color of the moon in a daylight sky, strange eyes, disturbing and at the same time fascinating. Basil realized after one glance at this frail old man in his short and unadorned woolen tunic that no one else in the room seemed to matter."When reading this for the first time, I found myself realizing that this is precisely how I had always pictured Paul in my head, which then led me to consider the fact that the description of Luke was so novel to me because I had never, for whatever reason, attempted to picture Luke in my head at all. I have no idea why.

The point, anyway, is that the books are absolutely worth your time. They are compelling and engaging reads, full of good humour and power. Give them a try, if you ever see them lying around. They tend to crop up in used book stores fairly frequently, so many great deals may be had. If you're more upscale, there's a new edition of The Silver Chalice currently available from Loyola Press which includes an introductory essay by the stalwart Peggy Noonan. It refers - darkly and understandably - to the contrast presented by a comparison of The Silver Chalice to The Da Vinci Code. Both books were at the top of the bestseller list for protracted periods of time, but, of course, fifty years apart. The difference is horrifying. If you can get this edition, or at least browse it briefly in the book store, it would surely be worthwhile.

==

Note: The Silver Chalice is further notable in that it was adapted into a kind of subpar film in 1954. This would be mildly interesting in its own right, but it's also worth noting that the film served as the launching point for Paul Newman's film career; he played the not insubstantial role of Basil. The film also features an astonishing turn by Jack Palance as Simon Magus, which is itself alone worth the effort to find it.

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Friday, October 06, 2006

Friday Round up....

I also wanted to mention Catholic Men's Quarterly here. I know that Eric has linked to it over at TDE. The Summer/Fall issue should be of interest to Chestertonians. The first article is by Dale Ahlquist, Sometimes You Have to Fight: A Chestertonian Perspective. Those who have listened to Dale shouldnt be surprised by the article, basically Chesterton and Just War. Some good quotes, though. Christopher Check, who spoke powerfully at the last GKC conference, has an article about Lepanto. For those of you who have read ACS's recent edition, Check begins a bit before in history, discussing more of the run-up to the battle. Yours truly contributes an article about mentoring and coaching.

www.arxpub.com is Arx Publishing, which publishes CMQ, as well as some very solid titles of high fantasy and literature.

It seems as though this time of year puts us in a Chestertonian octave. St. Michael, St. Francis, Our Lady of the Rosary(Lepanto) all find thier places on the calendar during this time. I suppose it is an opportunity for reflection on life, faith, and literature. What I have been deeply struck by recently is the liberating freedom which comes from faith. We are moral agents with power over our choices and direction. There is indeed nothing more depressing than the tyrannical slavery of being a prisoner of one's own time. It truly is the "orthodox" believer who can reach back in brotherhood with antiquity while still pressing on forward.

I have been reading a bit of Cardinal Newman lately, and it strikes me that the ideas which he expounded on regarding development of doctrine and the university are playing out in front of us today. I truly think that the cult of "progress" is winding down a bit, but the process of "evolution" guides our culture. Both progress and evolution taken out of context are nothing more than bad Calvanism featuring another kind of predestination and morbid inevitability. Reading Newman(and Chesterton) leaves me feeling in awe of the effort, time, and study required to produce a classically trained mind, and a razor sharp intellect. This is not merely an idea of Newman's, or of Western thought. Confucius himself did not think himself prepared to begin studying the I-Ching until he was past age 70. Pope John Paul II had spoken of evolution being a problem when it is "more than a hypothesis", indeed it is now a euphemism for our contemporary way of life. Evolution is passive, intellectual rigor is active. Matter can evolve into different forms, but ideas either develop as acorns into oak trees, or they suffer radical logical deficiencies. Keep your ears open for a couple days and you will be surprised how often the term "evolve" is used, albeit incorrectly.

Newman had also noticed that Theology had to be enshrined as the Queen of the Sciences. Im being a bit liberal with Newman, but he also noted that nature abhored a vacuum. Theology will always be present. Closing the theology departments of universities did not banish speculation into the highest questions of existence. The questions were only shifted to Marxist, Feminist, and GLBT doctrines.

Chesterton said that when one stopped believing in God, one would believe in anything. I think it is fairly easy to see examples of this all around us.

This is alot of heady stuff for Friday, but when you mention Newman you have no choice but to ascend into that air. I began this mental stroll with the idea of Christian faith empowering us with the ability to both reach back and move forward. I guess that the "Octave of Chesterton" has got me breathing the fresh air of orthodoxy, or the dank smell of the cave of Bethlehem. When man is the pinnacle of history and the incarnation is the pinnacle of man, there is always hope that a wonderful future can be built, not merely progress into being.

Thursday, October 05, 2006

Nickel Mines miracle

I am troubled by all violence, even when it is necessary, as in some wars or in the actions of a police officer protecting the public.

There is something darker, more evil, however, when the violence has no justification, and even darker yet when the victims are children.

This incident is hitting home even more, though, because of who the victims are.

The Amish have always seemed to me a people set apart.

I could not be one. I think they have some things wrong. But they are true to their beliefs in a way that humbles those of us who have sometimes compromised our Christian beliefs as we try to fit into the world.

One essential part of Christianity the Amish have tapped into is the command to "Love thy neighbor."

That is part of the horror of this crime. It was done by a neighbor, someone who knew them well.

Then again, as GKC observed, "The Bible tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because they are generally the same people."

The story of the man who did this is slowly unfolding. He was clearly a sick man, the evil in him festering over many years, ("Evil comes at leisure like the disease.")

But then, we get the Amish reaction of love.

They have not only forgiven the killer, they have reached out to his family, offering them comfort in the midst of their own grief, and even inviting them to at least one of the funerals.

Chesterton once observed, "Christianity has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and not tried."

Maybe he never met the Amish.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Fascinating Inconsistency

ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI

FOR most people there is a fascinating inconsistency in the position of St. Francis. He expressed in loftier and bolder language than any earthly thinker the conception that laughter is as divine as tears. He called his monks the mountebanks of God. He never forgot to take pleasure in a bird as it flashed past him, or a drop of water as it fell from his finger; he was perhaps the happiest of the sons of men. Yet this man undoubtedly founded his whole polity on the negation of what we think of the most imperious necessities; in his three vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience he denied to himself, and those he loved most, property, love, and liberty. Why was it that the most large-hearted and poetic spirits in that age found their most congenial atmosphere in these awful renunciations? Why did he who loved where all men were blind, seek to blind himself where all men loved? Why was he a monk and not a troubadour? We have a suspicion that if these questions were answered we should suddenly find that much of the enigma of this sullen time of ours was answered also.

G.K. Chesterton, Twelve Types

(from Chesterton Day by Day)Orthodoxy Review

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

Denying the Cat

In his 1908 masterpiece Orthodoxy, G. K. Chesterton explored the phenomenon of modern theologians who deny the reality of sin. "The strongest saints and the strongest skeptics alike took positive evil as the starting point of their argument," Chesterton wrote. "If it be true (as it certainly is) that a man can feel exquisite happiness skinning a cat, then the religious philosopher can make one or two deductions. He must either deny the existence of God, as all atheists do; or he must deny the present union between God and man, as all Christians do. The new theologians seem to think it a highly rationalistic solution to deny the cat."

There are no cats in The Conservative Soul, the new book by Andrew Sullivan. There is, however, tautology, narcissism, and enough moral relativism to light Manhattan for ten years. Sullivan's premise is simple: We just can't know anything for sure. There's no real truth, and anyone who claims otherwise is not really a conservative but rather a fundamentalist. "The essential claim of the fundamentalist is that he knows the truth," Sullivan writes. "The fundamentalist doesn't guess or argue or wonder or question. He doesn't have to. He knows." In opposition stands the true conservative, whose "defining characteristic" is that "he knows he doesn't know."

New Gilbert is Here

This issue revolves around the 25th Annual ACS Conference. Over 500 people attended. The first ACS Conference brought in twelve.

I've never ordered tapes from the conference, but I'm going to this time. I want to hear John Peterson's presentation about McLuhan and Chesterton. John is one of the most intelligent yet unpretentious individuals I've ever met. His quiet demeanor is a perfect yin to his forceful prose. He's also the guy who turned me onto McLuhan, thereby opening a whole new avenue of thought for me.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Owing to present circumstances

Fear not, however. The great oriental curse has come upon us! We live in interesting times, and you certainly don't need me to entertain, engross and horrify you. I'm sure you'll be able to get by, for now.