A site dedicated to G.K. Chesterton, his friends, and the writers he influenced: Belloc, Baring, Lewis, Tolkien, Dawson, Barfield, Knox, Muggeridge, and others.

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Hochhuth clerihew

In attacking Pope Pius Rolf Hochhuth

penned a play full of untruth.

Sadly, many an ignorant dope

now believes the myth of "Hitler's pope."

Friday, November 22, 2013

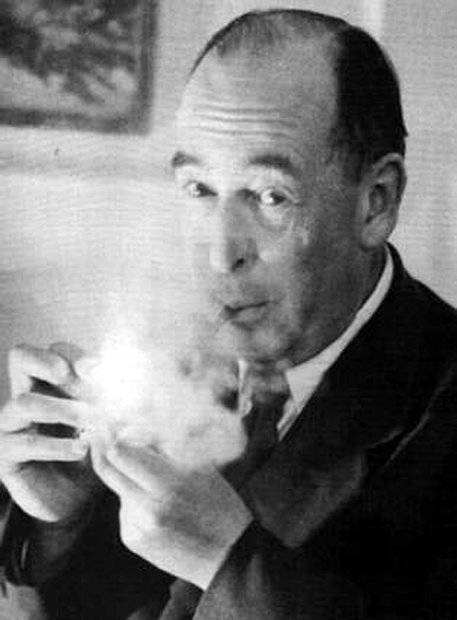

C. S.Lewis - Poet? (and his legacy)

To mark the 50th anniversary of his death, C. S. Lewis has been honored with a memorial stone in the Poet's Corner at Westminster Abbey.

To be honest, I've never thought of Lewis as a poet. I love him for his theological works and his fiction. (Sort of like my thoughts about Chesterton.) I don't think I even own a collection of Lewis's poetry. (I own several volumes of Chesterton's - and have enjoyed them.)

I do remember one self-deprecating poem of Lewis's:

A Confession

I am so coarse, the things the poets see

Are obstinately invisible to me.

For twenty years I’ve stared my level best

To see if evening–any evening–would suggest

A patient etherized upon a table;

In vain. I simply wasn’t able.

To me each evening looked far more

Like the departure from a silent, yet a crowded, shore

Of a ship whose freight was everything, leaving behind

Gracefully, finally, without farewells, marooned mankind.

Red dawn behind a hedgerow in the east

Never, for me, resembled in the least

A chilblain on a cocktail-shaker’s nose;

Waterfalls don’t remind me of torn underclothes,

Nor glaciers of tin-cans. I’ve never known

The moon look like a hump-backed crone–

Rather, a prodigy, even now

Not naturalized, a riddle glaring from the Cyclops’ brow

Of the cold world, reminding me on what a place

I crawl and cling, a planet with no bulwarks, out in space.

Never the white sun of the wintriest day

Struck me as un crachat d’estaminet.

I’m like that odd man Wordsworth knew, to whom

A primrose was a yellow primrose, one whose doom

Keeps him forever in the list of dunces,

Compelled to live on stock responses,

Making the poor best that I can

Of dull things . . . peacocks, honey, the Great Wall, Aldebaran,

Silver weirs, new-cut grass, wave on the beach, hard gem,

The shapes of horse and woman, Athens, Troy, Jerusalem.

I need to dig out more of his poems.

Today is also the anniversary of the death of John Kennedy, whose tragic death overshadowed that of Lewis.

While both men had an impact on the world, I think Lewis's influence will ultimately be greater.

Kennedy's legacy is based on his incomplete term as President. The record was mixed - but his assassination and the emotional impact of his death overwhelmed objectivity in assessing that record. He's a martyr, a romantic tragic figure. I suspect that when the dust of history settles he will be judged somewhere in the second tier of presidents (in the 14/15 range). One has to wonder what he would have achieved had he finished out his term - and, as I suspect he would have - served out a second term.

But Lewis has only grown in stature since his death. His Mere Christianity is ranked as one of the spiritual classics of the 20th Century. His Chronicles of Narnia books and The Screwtape Letters also rank high. They - and a number of his other books - continue to sell briskly and to influence people. Many people have discovered or rediscovered faith through his works, and, through the case of Narnia, the movies made from them.

I suspect years from now people will still be reading and cherishing Lewis's writings.

Long after Kennedy's achievements are relegated to the history books.

But I'm still not certain how Lewis's poetry will be remembered.

Thursday, November 07, 2013

Chesterton ad

Ah, the great one keeps showing up in different places.

Up here in Western New York a local car company quotes Chesterton in an ad:

http://www.thatsmyvision.com/custom/vision-tv/

The ad begins with Chesterton saying "The greatest for of giving is Thanks-Giving."

The company says it will donate to a local charity during November, so maybe Chesterton would object to his name being linked to commercial venture.

Sunday, September 22, 2013

Rochester Chesterton Conference 2013 (images)

Dale Ahlquist hawking some shirts to raise money for the ACS.

Lou Horvath offering greetings, but no explanations ...

Deacon Nathan Allen making a point, not picking nits.

Despite Dale's jokes at his expense, Joseph Pearce still likes him. We think. Tom Martin seems to be trying to stay out of the fray.

A good time was had by all.

So, which character in the The Hobbit would you be?

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Rochester Chesterton Conference - September 21

The Chestertonians are coming! The Chestertonians are coming!

The annual Rochester Chesterton Conference is scheduled for September from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. at St John Fisher College .

The theme this year is:

Points of Light: Literary Voices Against the Darkness

The speakers and their topics are Joseph Pearce (JRR Tolkien), Rev. Nathan Allen (Benson and Knox),

Dale Ahlquist (Dickens), and Dr. Tom Martin (Solzhenitsyn).

Cost is $10, Lunch will be available for an added cost.

Always a great event. If you are within a few hours' drive, wander on over.

Friday, September 06, 2013

Ball-less sports

You too can be an imagination captain. Don't forget to click on listen these guys are channeling Bob and Ray

Monday, September 02, 2013

Playground Politics

When the

republican's are 'in the house' the media says war is evil and the pres is an enemy

to the people. When the dems are in office the media says war is a necessary

evil and the pres is saving the people. Our current occupant dragged his heel across the sand box when he said: "Use of chemical weapons by

Syria would cross a ‘red line’". Well Syria crossed it and said 'You talkin to me?"

now Obama is stuck pulling on the rope of

war.

As Khrushchev

said when Russia and the US were on the brink of war: "If you did this as the first step towards the unleashing

of war, well then, it is evident that nothing else is left to us but to accept

this challenge of yours. If, however, you have not lost your self-control and

sensibly conceive what this might lead to, then, Mr. President, we and you

ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot

of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be

tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he

who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be

necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain

to you, because you yourself understand perfectly of what terrible forces our

countries dispose. (read the whole letter here).

So the question for

the day has Obama lost his self control? Can he back down from a double dog

dare? does he have a plan after he pulls the trigger? Put simply: Just war-making requires clearly articulated and substantive goals. Launching cruise missiles or air strikes simply to “show resolve” or “send a message” cannot be justified. At the end of the day, these rationales authorize symbolic killing,which is fundamentally immoral.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Lift a Glass

It has been suggested the GKC be made patron saint of beer drinkers. If that happens he will be in good company

auggy doggy day

St. Augustine feast day today - he showed us the truth:

"The mass of men have been forced to be gay about the little things, but sad about the big ones. Nevertheless (I offer my last dogma defiantly) it is not native to man to be so. Man is more himself, man is more manlike, when joy is the fundamental thing in him, and grief the superficial. Melancholy should be an innocent interlude, a tender and fugitive frame of mind; praise should be the permanent pulsation of the soul. Pessimism is at best an emotional half-holiday; joy is the uproarious labour by which all things live. Yet, according to the apparent estate of man as seen by the pagan or the agnostic, this primary need of human nature can never be fulfilled. Joy ought to be expansive; but for the agnostic it must be contracted, it must cling to one corner of the world. Grief ought to be a concentration; but for the agnostic its desolation is spread through an unthinkable eternity. This is what I call being born upside down. The sceptic may truly be said to be topsy-turvy; for his feet are dancing upwards in idle ecstasies, while his brain is in the abyss. To the modern man the heavens are actually below the earth. The explanation is simple; he is standing on his head; which is a very weak pedestal to stand on. But when he has found his feet again he knows it. Christianity satisfies suddenly and perfectly man's ancestral instinct for being the right way up; satisfies it supremely in this; that by its creed joy becomes something gigantic and sadness something special and small. The vault above us is not deaf because the universe is an idiot; the silence is not the heartless silence of an endless and aimless world. Rather the silence around us is a small and pitiful stillness like the prompt stillness in a sick-room. We are perhaps permitted tragedy as a sort of merciful comedy: because the frantic energy of divine things would knock us down like a drunken farce. We can take our own tears more lightly than we could take the tremendous levities of the angels. So we sit perhaps in a starry chamber of silence, while the laughter of the heavens is too loud for us to hear." Orthodoxy

"You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you."

Thus Joy is found.

Which brings us to Uncle Gilbert

|

You can not steal the Joy of a Christian.

Monday, August 26, 2013

A Few "Comic" Clerihews

I've never seen Steve Martin

in tartan.

But to me he doesn't look right

in anything but white.

Kathy Griffin

Likes to joke about sexual sin.

But to be honest all she does is bore

When she tries to play the whore.

Steven Wright

Is right:

Boycott shampoo,

demand the real poo.

I sometimes think Frankie Boyle

Fills his mouth with soil.

As for his jokes, he’s out of luck:

I won’t repeat anything containing words like #@&!

Saturday, August 24, 2013

Banned in New York

New York City has gotten a reputation for banning strange things - like large soft drinks. That one is thanks to mayor Bloomberg,

But the NY Department of Education have topped him.

They've banned certain words and phrases from class rooms and tests. They don't want the children to feel "bad."

Being ignorant is apparently acceptable, though.

Imagine trying to teach history without using words like "slavery" or "war." Or science without "tsunamis" or "evolution."

"Religion" also made the no-no list - but we kind of knew that.

So has "witchcraft" - but that seems fair given that religion ban.

Oh, and don't mention "sex" or "pornography" or even "television" - given the predominance of the first two on television shows that makes sense.

GKC might take exception to the ban on "alcohol" or tobacco products.

And don't bring up "cancer" or "politics" - which seem to be related anyway.

Here's a list of words and phrases to avoid:

- Abuse (physical, sexual, emotional, or psychological)

- Alcohol (beer and liquor), tobacco, or drugs

- Birthday celebrations (and birthdays)

- Bodily functions

- Cancer (and other diseases)

- Catastrophes/disasters (tsunamis and hurricanes)

- Celebrities

- Children dealing with serious issues

- Cigarettes (and other smoking paraphernalia)

- Computers in the home (acceptable in a school or library setting)

- Crime

- Death and disease

- Divorce

- Evolution

- Expensive gifts, vacations, and prizes

- Gambling involving money

- Halloween

- Homelessness

- Homes with swimming pools

- Hunting

- Junk food

- In-depth discussions of sports that require prior knowledge

- Loss of employment

- Nuclear weapons

- Occult topics (i.e. fortune-telling)

- Parapsychology

- Politics

- Pornography

- Poverty

- Rap Music

- Religion

- Religious holidays and festivals (including but not limited to Christmas, Yom Kippur, and Ramadan)

- Rock-and-Roll music

- Running away

- Sex

- Slavery

- Terrorism

- Television and video games (excessive use)

- Traumatic material (including material that may be particularly upsetting such as animal shelters)

- Vermin (rats and roaches)

- Violence

- War and bloodshed

- Weapons (guns, knives, etc.)

- Witchcraft, sorcery, etc.

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

in support of his cause.

A 300 lb cigar smoking

saint? Cool. When he gets his plaque put up in the catholic hall of fame, aka

sainthood, to who or what will he be crowned patron saint? Before answering keep

in mind the type of sense of humor the Church has, St. Lawrence is the patron of barbecue and St Steven is

the patron of stonemasons. Maybe St Gilbert will be the patron saint of runway models.

Tuesday, August 20, 2013

More on St. Chesterton (okay, jumping the gun)

In Crisis Magazine, Dale Ahlquist talks about the news that the first step in a potential cause for canonization of Chesterton has begun. He explains it far better than I can.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

More on Chesterton's Cause

Sainthood on the Horizon for G.K. Chesterton?: An investigation has begun into whether to open the cause for canonization of the English writer and convert.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Prayer for the intercession of Chesterton

In light of the first steps in the possible start of Chesterton's cause, here's a prayer from the American Chesterton Society:

Prayer for the intercession of G. K. Chesterton

God our Father,

You filled the life of your servant Gilbert Keith Chesterton with a sense of wonder and joy, and gave him a faith which was the foundation of his ceaseless work, a hope which sprang from his enduring gratitude for the gift of human life, and a charity towards all men, particularly his opponents.

May his innocence and his laughter, his constancy in fighting for the Christian faith in a world losing belief, his lifelong devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary and his love for all men, especially for the poor, bring cheerfulness to those in despair, conviction and warmth to lukewarm believers and the knowledge of God to those without faith.

We beg you to grant the favors we ask through his intercession, [and especially for ……] so that his holiness may be recognized by all and the Church may proclaim him Blessed.

We ask this through Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Friday, August 02, 2013

NPR's sci fi/fantasy list - read the usual suspects

NPR has put out a list of the top 100 science fiction and fantasy novels.

I looked at the list with interest, having been a fan of such fiction for a long time.

I was bemused to find I had read only 33 of the 100 books on the list. Hmm. I need to do more reading!

There are a couple of givens. J. R.R. Tolkien made it with The Lord of the Rings. And C. S. Lewis made it with his science fiction trilogy. Tolkien's The Silmarillion also made the list, which pleased me.

And Walter Miller's great A Canticle for Leibowitz made it.

But there were a number of missing titles - including anything by Chesterton. I consider The Man Who Was Thursday or The Napoleon of Notting Hill better than some of the titles on the list.

Other notable missing titles include Tolkien's The Hobbit, and Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia and The Screwtape Letters. I could also put in a word for Lewis's Till We Have Faces - his retelling of the Cupid and Psyche myth.

Or how about A Case of Conscience by James Blish, about a race on another planet that is completely moral and ethical with no belief in or sense of God or religion? Or anything by Madeleine L'Engle (A Wrinkle in Time, A Wind in the Door, or A Swiftly Tilting Planet)?

To be fair, maybe the people selection decided L'Engle's books, or Narnia, or even The Hobbit children's books and that's why they didn't pick them. But I'd argue that they are still better than some of the other books on the list. Oh well: All such lists are subjective.

It's an interesting list and a good conversation/debate starter. What titles would other folks include that would be of interest to Chestertonians?

St. Gilbert?

Here is the reported wording from Dale Ahlquist's announcement at the GKC conference:

"Martin Thompson says that Bishop Peter Doyle 'has given me permission to report that the Bishop of Northampton is sympathetic to our wishes and is seeking a suitable cleric to begin an investigation into the potential for opening a cause for Chesterton.'"

Okay - qualified, just a possible start, but at least it's movement!

Saturday, July 27, 2013

Happy Birthday Hilaire

He's the fellow in the center. Anyone know who the other two gents are? (wink)

Today is Hilaire Belloc's birthday.

Were he still alive - instead of dying 60 years ago this month - he would be 143 years old.

While he did not live on, his writings have.

A toast to him.

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Chesterton on Hermits

I have long been interested in and attracted to the hermit life. I've chosen to live in the world - my wife would be upset if I suddenly headed off to the woods - but the desire for solitude still tugs at my heart and soul.

Still, there have been efforts to help those so incli8ned to lead a modified eremetical life while still living actively in the world. Catherine Doherty's fine spiritual book, Poustinia, describes one method. Some people also take periodic breaks from the world to go off to hermitages periodically for some alone time. And there is even Raven's Bread Hermit Ministries, which has a newsletter, a website, and books to help support those inclined to solitude.

Chesterton was not a hermit. He enjoyed getting out in public for a drink, a talk, a debate, conversation, and so on. He did address the subject of hermits in a wonderful essay, "The Case for Hermits," contained in The Well and the Shallows.

Chesterton noted that the hermits, the solitaries, are often considered "savages or man-haters" by a society that regards being sociable as the norm. But he pointed out this was not the case: "But many of them really had charity--even to human beings. They felt more kindly about men than men in the Forum or the Mart felt about each other."

In fact, he observed, "The reason why even the normal human being should be half a hermit is that it is the only way in which his mind can have a half-holiday. It is the only way to get any fun even out of the facts of life; yes, even if the facts are games and dances and operas."

So for us semi-hermits our time alone is like a holiday. That makes sense to me. My wife, aware of my need for alone time, periodically goes off shopping or with friends just to give me an afternoon alone - a mini holiday. And as a teacher, summer is often a daily holiday, with lots of time alone. I use that time to get things done - mowing the lawn, painting the fence, trimming the bushes, etc. - but also to pray, walk in the woods, meditate.

I know for me my time alone enables me to be more kindly disposed toward others. As Chesterton said, "It is in society that men quarrel with their friends; it is in solitude that they forgive them. And before the society-man criticises the saint, let him remember that the man in the desert often had a soul that was like a honey-pot of human kindness, though no man came near to taste it; and the man in the modern salon, in his intellectual hospitality, generally serves out wormwood for wine."

Here's his full essay:

Anyone who has ever protected a little boy from being bullied at school, or a little girl from some childish persecution at a party, or any natural person from any minor nuisance, knows that the being thus badgered tends to cry out, in a simple but singular English idiom, "Let me alone!" It is seldom that the child of nature breaks into the cry, "Let me enjoy the fraternal solidarity of a more socially organised group-life." It is rare even for the protest to leap to the lips in the form, "Let me run around with some crowd that has got dough enough to hit the high spots." Not one of these positive modern ideals presents itself to that untutored mind; but only the ideal of being "let alone." It is rather interesting that so spontaneous, instinctive, almost animal an ejaculation contains the word alone.

There are now a great many boys and girls, both old and young, who are really in that state of mind; not only through being teased, but also through being petted. Most of them will fiercely deny it, since it contradicts the conventions of their new generation; just as a child kept up too late at night will more and more indignantly deny the desire to go to bed. Indeed I am always expecting to hear that a scientific campaign has been opened against Sleep. Sooner or later the Prohibitionists will turn their attention to the old tribal traditional superstition of Sleep; and they will say that the sluggard is merely encouraged by the cowardice of the moderate sleeper. There will be tables of statistics, showing how many hours of output are lost by miners, smelters, plumbers, plasterers, and every trade in which (it will be noted) men have contracted the habit of sleep; tables showing the shortage of aconite, alum, apples, beef, beetroot, bootlaces, etc., and other statistics carefully demonstrating that work of this kind can only rarely be performed by sleep-walkers. There will be all the scientific facts, except one scientific fact. And that is the fact that if men do not have Sleep, they go mad. It is also a fact that if men do not have Solitude, they go mad. You can see that, by the way they go on, when the poor miserable devils only have Society.

The incident of Miss Fitzpatrick, the lady who really liked to be alone, challenges all recent fashions, which are all for Society without Solitude. We must Get Together; as the gunman said when he ran his machine-gun into two other machine-guns and killed all the children caught between them. And we know that this sociability and communal organisation has already produced in fashionable society all that sweetness and light, all that courtesy and charity, all that True Christianity of pardon and patience, which we see in the modern organisers of gangs or "group-life." In contrast with this happy mood now pervading our literature and conversation, it is customary to point to hermits and solitaries as if they were savages and man-haters.

But it is not true. It is not true in History or human fact. The line that ran, "Turn, gentle hermit of the Vale," was truer to the real tradition about the real hermits. They were doubtless, from a modern standpoint, lunatics; but they were nice lunatics. Twenty touches could illustrate what I mean; for instance, the fact that they could make pets of the wild animals that came naturally to them. But many of them really had charity--even to human beings. They felt more kindly about men than men in the Forum or the Mart felt about each other. Doubtless there have been merely sulky solitaries; unquestionably there have been sham cynics and cabotins, like Diogenes. But he and his sort are very careful not to be really solitary; careful to hang about the market-place like any demagogue. Diogenes was a tub-thumper, as well as a tub-dweller. And that sort of professional sulks remains; but it is sulks without solitude. We all know there are geniuses, who must go out into polite society in order to be impolite. We all know there are hostesses who collect lions and find they have got bears. I fear there was a touch of that in the social legend of Thomas Carlyle and perhaps of Tennyson. But these men must have a society in which to be unsociable. The hermits, especially the saints, had a solitude in which to be sociable.

St. Jerome lived with a real lion; a good way to avoid being lionised. But he was very sociable with the lion. In his time, as in ours, sociability of the conventional sort had become social suffocation. In the decline of the Roman Empire, people got together in amphitheatres and public festivals, just as they now get together in trams and tubes. And there were the same feelings of mutual love and tenderness, between two men trying to get a seat in the Colosseum, as there are now between two men trying to get the one remaining seat on a Tooting tram. Consequently, in that last Roman phase, all the most amiable people rushed away into the desert, to find what is called a hermitage; but might almost be called a holiday. The man was a hermit because he was more of a human being; not less. It was not merely that he felt he could get on better with a lion than with the sort of men who would throw him to the lions. It was also that he actually liked men better when they let him alone. Now nobody expects anybody, except a very exceptional person, to become a complete solitary. But there is a strong case for more Solitude; especially now that there is really no Solitude.

The reason why even the normal human being should be half a hermit is that it is the only way in which his mind can have a half-holiday. It is the only way to get any fun even out of the facts of life; yes, even if the facts are games and dances and operas. It bears most resemblance to the unpacking of luggage. It has been said that we live on a railway station; many of us live in a luggage van; or wander about the world with luggage that we never unpack at all. For the best things that happen to us are those we get out of what has already happened. If men were honest with themselves, they would agree that actual social engagements, even with those they love, often seem strangely brief, breathless, thwarted or inconclusive. Mere society is a way of turning friends into acquaintances, the real profit is not in meeting our friends, but in having met them. Now when people merely plunge from crush to crush, and from crowd to crowd, they never discover the positive joy of life. They are like men always hungry, because their food never digests; also, like those men, they are cross. There is surely something the matter with modern life when all the literature of the young is so cross. That is something of the secret of the saints who went into the desert. It is in society that men quarrel with their friends; it is in solitude that they forgive them. And before the society-man criticises the saint, let him remember that the man in the desert often had a soul that was like a honey-pot of human kindness, though no man came near to taste it; and the man in the modern salon, in his intellectual hospitality, generally serves out wormwood for wine.

In conclusion, I will take one very modern and even topical case. I do not believe in Communism, certainly not in compulsory Communism. And it is typical of this acrid age that what we all discuss is compulsory Communism. I often sympathise with Communists, which is quite a different thing; but even these I respect rather as bold or honest or logical than as particularly genial or kindly. Nobody will claim that modern Communism is a specially sweet-tempered or amiable thing. But if you will look up the legends of the earliest Hermits, you will find a very charming anecdote, about two monks who really were Communists. And one of them tried to explain to the other how it was that quarrels arose about private property. So he thumped down a stone and observed theatrically, "This stone is mine." The other, slightly wondering at his taste, said, "All right; take it." Then the teacher of economics became quite vexed and said, "No, no; you mustn't say that. You must say it is yours; and then we can fight." So the second hermit said it was his; whereupon the first hermit mechanically gave it up; and the whole lesson in Business Methods seems to have broken down. Now you may agree or disagree with the Communist ideal, of cutting oneself off from commerce, which those two ascetics followed. But is there not something to suggest that they were rather nicer people than the Communists we now meet in Society? Somehow as if Solitude improved the temper?

Still, there have been efforts to help those so incli8ned to lead a modified eremetical life while still living actively in the world. Catherine Doherty's fine spiritual book, Poustinia, describes one method. Some people also take periodic breaks from the world to go off to hermitages periodically for some alone time. And there is even Raven's Bread Hermit Ministries, which has a newsletter, a website, and books to help support those inclined to solitude.

Chesterton was not a hermit. He enjoyed getting out in public for a drink, a talk, a debate, conversation, and so on. He did address the subject of hermits in a wonderful essay, "The Case for Hermits," contained in The Well and the Shallows.

Chesterton noted that the hermits, the solitaries, are often considered "savages or man-haters" by a society that regards being sociable as the norm. But he pointed out this was not the case: "But many of them really had charity--even to human beings. They felt more kindly about men than men in the Forum or the Mart felt about each other."

In fact, he observed, "The reason why even the normal human being should be half a hermit is that it is the only way in which his mind can have a half-holiday. It is the only way to get any fun even out of the facts of life; yes, even if the facts are games and dances and operas."

So for us semi-hermits our time alone is like a holiday. That makes sense to me. My wife, aware of my need for alone time, periodically goes off shopping or with friends just to give me an afternoon alone - a mini holiday. And as a teacher, summer is often a daily holiday, with lots of time alone. I use that time to get things done - mowing the lawn, painting the fence, trimming the bushes, etc. - but also to pray, walk in the woods, meditate.

I know for me my time alone enables me to be more kindly disposed toward others. As Chesterton said, "It is in society that men quarrel with their friends; it is in solitude that they forgive them. And before the society-man criticises the saint, let him remember that the man in the desert often had a soul that was like a honey-pot of human kindness, though no man came near to taste it; and the man in the modern salon, in his intellectual hospitality, generally serves out wormwood for wine."

Here's his full essay:

Anyone who has ever protected a little boy from being bullied at school, or a little girl from some childish persecution at a party, or any natural person from any minor nuisance, knows that the being thus badgered tends to cry out, in a simple but singular English idiom, "Let me alone!" It is seldom that the child of nature breaks into the cry, "Let me enjoy the fraternal solidarity of a more socially organised group-life." It is rare even for the protest to leap to the lips in the form, "Let me run around with some crowd that has got dough enough to hit the high spots." Not one of these positive modern ideals presents itself to that untutored mind; but only the ideal of being "let alone." It is rather interesting that so spontaneous, instinctive, almost animal an ejaculation contains the word alone.

There are now a great many boys and girls, both old and young, who are really in that state of mind; not only through being teased, but also through being petted. Most of them will fiercely deny it, since it contradicts the conventions of their new generation; just as a child kept up too late at night will more and more indignantly deny the desire to go to bed. Indeed I am always expecting to hear that a scientific campaign has been opened against Sleep. Sooner or later the Prohibitionists will turn their attention to the old tribal traditional superstition of Sleep; and they will say that the sluggard is merely encouraged by the cowardice of the moderate sleeper. There will be tables of statistics, showing how many hours of output are lost by miners, smelters, plumbers, plasterers, and every trade in which (it will be noted) men have contracted the habit of sleep; tables showing the shortage of aconite, alum, apples, beef, beetroot, bootlaces, etc., and other statistics carefully demonstrating that work of this kind can only rarely be performed by sleep-walkers. There will be all the scientific facts, except one scientific fact. And that is the fact that if men do not have Sleep, they go mad. It is also a fact that if men do not have Solitude, they go mad. You can see that, by the way they go on, when the poor miserable devils only have Society.

The incident of Miss Fitzpatrick, the lady who really liked to be alone, challenges all recent fashions, which are all for Society without Solitude. We must Get Together; as the gunman said when he ran his machine-gun into two other machine-guns and killed all the children caught between them. And we know that this sociability and communal organisation has already produced in fashionable society all that sweetness and light, all that courtesy and charity, all that True Christianity of pardon and patience, which we see in the modern organisers of gangs or "group-life." In contrast with this happy mood now pervading our literature and conversation, it is customary to point to hermits and solitaries as if they were savages and man-haters.

But it is not true. It is not true in History or human fact. The line that ran, "Turn, gentle hermit of the Vale," was truer to the real tradition about the real hermits. They were doubtless, from a modern standpoint, lunatics; but they were nice lunatics. Twenty touches could illustrate what I mean; for instance, the fact that they could make pets of the wild animals that came naturally to them. But many of them really had charity--even to human beings. They felt more kindly about men than men in the Forum or the Mart felt about each other. Doubtless there have been merely sulky solitaries; unquestionably there have been sham cynics and cabotins, like Diogenes. But he and his sort are very careful not to be really solitary; careful to hang about the market-place like any demagogue. Diogenes was a tub-thumper, as well as a tub-dweller. And that sort of professional sulks remains; but it is sulks without solitude. We all know there are geniuses, who must go out into polite society in order to be impolite. We all know there are hostesses who collect lions and find they have got bears. I fear there was a touch of that in the social legend of Thomas Carlyle and perhaps of Tennyson. But these men must have a society in which to be unsociable. The hermits, especially the saints, had a solitude in which to be sociable.

St. Jerome lived with a real lion; a good way to avoid being lionised. But he was very sociable with the lion. In his time, as in ours, sociability of the conventional sort had become social suffocation. In the decline of the Roman Empire, people got together in amphitheatres and public festivals, just as they now get together in trams and tubes. And there were the same feelings of mutual love and tenderness, between two men trying to get a seat in the Colosseum, as there are now between two men trying to get the one remaining seat on a Tooting tram. Consequently, in that last Roman phase, all the most amiable people rushed away into the desert, to find what is called a hermitage; but might almost be called a holiday. The man was a hermit because he was more of a human being; not less. It was not merely that he felt he could get on better with a lion than with the sort of men who would throw him to the lions. It was also that he actually liked men better when they let him alone. Now nobody expects anybody, except a very exceptional person, to become a complete solitary. But there is a strong case for more Solitude; especially now that there is really no Solitude.

The reason why even the normal human being should be half a hermit is that it is the only way in which his mind can have a half-holiday. It is the only way to get any fun even out of the facts of life; yes, even if the facts are games and dances and operas. It bears most resemblance to the unpacking of luggage. It has been said that we live on a railway station; many of us live in a luggage van; or wander about the world with luggage that we never unpack at all. For the best things that happen to us are those we get out of what has already happened. If men were honest with themselves, they would agree that actual social engagements, even with those they love, often seem strangely brief, breathless, thwarted or inconclusive. Mere society is a way of turning friends into acquaintances, the real profit is not in meeting our friends, but in having met them. Now when people merely plunge from crush to crush, and from crowd to crowd, they never discover the positive joy of life. They are like men always hungry, because their food never digests; also, like those men, they are cross. There is surely something the matter with modern life when all the literature of the young is so cross. That is something of the secret of the saints who went into the desert. It is in society that men quarrel with their friends; it is in solitude that they forgive them. And before the society-man criticises the saint, let him remember that the man in the desert often had a soul that was like a honey-pot of human kindness, though no man came near to taste it; and the man in the modern salon, in his intellectual hospitality, generally serves out wormwood for wine.

In conclusion, I will take one very modern and even topical case. I do not believe in Communism, certainly not in compulsory Communism. And it is typical of this acrid age that what we all discuss is compulsory Communism. I often sympathise with Communists, which is quite a different thing; but even these I respect rather as bold or honest or logical than as particularly genial or kindly. Nobody will claim that modern Communism is a specially sweet-tempered or amiable thing. But if you will look up the legends of the earliest Hermits, you will find a very charming anecdote, about two monks who really were Communists. And one of them tried to explain to the other how it was that quarrels arose about private property. So he thumped down a stone and observed theatrically, "This stone is mine." The other, slightly wondering at his taste, said, "All right; take it." Then the teacher of economics became quite vexed and said, "No, no; you mustn't say that. You must say it is yours; and then we can fight." So the second hermit said it was his; whereupon the first hermit mechanically gave it up; and the whole lesson in Business Methods seems to have broken down. Now you may agree or disagree with the Communist ideal, of cutting oneself off from commerce, which those two ascetics followed. But is there not something to suggest that they were rather nicer people than the Communists we now meet in Society? Somehow as if Solitude improved the temper?

Thursday, July 11, 2013

A Catholic Reading List

Father John McCloskey over at Catholicity.com has compiled A Catholic Lifetime Reading Plan. He is not alone in having done this - I even remember a book by that title by Father Hardon a few years back.

There are a number of interesting titles on Father McCloskey's list - including ones by some of our favorite authors here.

Chesterton shows up with four titles: Everlasting Man, Orthodoxy, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Francis of Assisi. I can't argue with any of those choices. I wonder if an essay collection could be added - but which one? (Maybe In Defense of Sanity, selected by Ahlquist, Mackey, and Pearce?)

If I read the list correctly, by the way, Chesterton has the most individual titles listed. However, Father does say "Opera Omnia" (the complete works) for Popes Benedict XVI and John Paul II.

Belloc shows up with three titles: The Great Heresies, How The Reformation Happened, and Survivals and New Arrivals, Alas, no room for his poetry!

C. S. Lewis also has three titles: The Problem of Pain, Mere Christianity, and The Screwtape Letters. No Narnia. Interestingly, Fathers has a typo here, calling the first book the Problem with Pain! And, of course, Lewis' good friend, J. R. R. Tolkien, makes the list with The Lord of Rings. Since that was published as a trilogy, maybe we should count that as three titles.

Among the other authors associated with this blog who made the list are Christopher Dawson, Christianity and European Culture; Monsignor Ronald Knox, Enthusiasm; and Malcolm Muggeridge, Something Beautiful for God ( a lovely book about Mother Teresa).

There are other favorite of mine:

Dorothy Day – The Long Loneliness

Scott Hahn – Rome Sweet Home

Pope John XXIII – Journal of a Soul

Thomas Merton – Seven Storey Mountain

Gerard Manley Hopkins (poetry)

Confessions of St. Augustine

There are plenty of other titles I'd like to read. I think maybe the list could have more poetry (Date made the list, by the way.) And drama - though of course plays are more meant to be watched than read (ah, but something like A Man for All Seasons is a wonderful read.)

Now, what should I read next?

Sunday, June 30, 2013

Our St. Thomas More Moment

"Sir Thomas More is more important at this moment than at any moment since his death, but he is not quite so important as he will be in a hundred years time." - G. K. Chesterton, in 1919

At our school we've added classic/significant movies to our English summer reading lists to help promote cultural literacy. For the seniors, who are taking what's basically a British literature course, the movie is A Man for All Seasons.

I've always loved that movie. I've also had a fondness for St. Thomas More for his faith and his courage, but also for the fact that he was a Secular Franciscan.

He's been on my mind lately.

More died because he refused to go along with King Henry's desired to challenge the Church over it marriage rules. Henry wanted the pope to grant him an annulment from his first marriage - never mind that the pope had given his special permission to marry Catherine of Aragon in the first place - but the pope refused. So Henry broke from the Church, dissolved the marriage, and married Anne Boleyn.

More sided with the Church, and quit his government post. But he also did not say anything, hoping that as long as he did not publicly states his views he and his family would remain safe. As the movie makes clear, he did not even tell his family his views so that they could not be called upon to testify.

But everyone knew where he stood.

Henry then got a law approved that required people to swear that they supported the King - and thus More's silence could no longer protect him.

I was thinking about More because we are faced with another marriage issue - and one in which people of faith are increasingly being forced to go along or face persecution.

The current issue is, of course, homosexual so-called marriage. The U.S. Supreme Court decisions last week are just another step in the process toward legal recognition of such marriages - which are allowed in a number of states (including my own).

We've received all sorts of assurances that churches will not be forced to perform such wedding ceremonies, and that people will not be forced to go against their religious beliefs when it comes to such marriages.

But it's already begun to happen - and it will increase.

People who defend traditional marriage can't do so at work. If they speak out, they can be fired. Some had hoped they could simply keep their mouths shut, but in some government agencies they are now required to at least pretend they support such marriages - just as Henry required peopel to take an oth in support of his marriage and defiance of the Church. Some government workers who perform wedding have already been forced to quit their jobs because they will be required to perform such weddings.

Meanwhile, photographers, florists, inn keepers, and more have been sued if they have declined to provide their services for marriages and couple they don't recognize on moral grounds.

There are more and more stories of people facing persecution because they do not go along with the homosexual agenda. Like More, they are increasingly not protected by silence.

We are faced with the kind of choice More faced. He provides an important model for us. We too may be called upon to pay a price for upholding our beliefs and our Church (though, we don't face death for doing so, at least not yet).

It seems that Chesterton's 1919 prediction is indeed coming true a century later.

Thursday, June 13, 2013

C. S. Lewis Conference Next Week

This November 22 will mark the 50th anniversary of the death of C. S. Lewis.

To mark the anniversary The C. S. Lewis Foundation has scheduled the C. S. Lewis Summer Conference for June 21-23 in San Diego at the University of San Diego.

The theme is "Living Legacy: The Vision, Voice & Vocation of C. S. Lewis."

Among the scheduled speakers is Peter Kreeft - who's also scheduled for the Chesterton Conference in Massachusetts August 1-3.

The breakout sessions include Doing What the Inklings Did, Between Heaven and Hell, Did C. S. Lewis Get it Wrong, Lewis and Women, the Art of Prayer, and The Screwtape Letter: C. S. Lewis' Other Autobiography.

Sound interesting. For West Coast folk who can't make it to the Chesterton Conference, this might be a reasonable alternative.

For more info go here.

Saturday, June 08, 2013

Chesterton is indeed "The Complete Thinker"

I've just read The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G. K. Chesterton by Dale Ahlquist.

I'd recommend that fans of Chesterton do so too - and not just because buying a copy might put a few bucks in Dale's pocket (though he deserves it).

The book is a survey of Chesterton's thinking on any number of issues and topics. Given the range of Chesterton's writings the book needed an appendix to try to fit everything in - and I suspect Dale could have added another appendix or two if he'd wanted to.

Chesterton was noted for inserting himself and his thought into everything he was writing, so it's no surprise that amidst the exploration of GKC's thoughts, Ahquist also managed to sneak in bits of his own Chesterton-colored observations about contemporary issues.

Given the volume of Chesterton's writings and the range of topics he covered, the book is by necessity only a taste of Chesterton. But it might just inspire readers to explore him more seriously and more in depth. Although I have been reading Chesterton fairly regularly for the past 20 years, I learned a few things from this book - and made some connections I hadn't before.

I found reading the book like reading Chesterton - at least for me. Some people can guzzle his writing. I find I need to sip and savor. So it takes me a while to get through any of Chesterton's books. It took me months to finish Ahlquist's book. Better minds would likely be able to get through it much quicker.

But whatever your approach, I do recommend this book. Even if you are not a fan of Chesterton, I think you'll find this book thought-provoking and eye-opening.

So buy it, and keep Dale's bank account solvent.

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Happy Birthday Chesterton

Happy Birthday (yesterday)!

“Children are grateful when Santa Claus puts in their stockings gifts of toys or sweets. Could I not be grateful to Santa Claus when he put in my stockings the gift of two miraculous legs? We thank people for birthday presents of cigars and slippers. Can I thank no one

for the birthday present of birth?”

for the birthday present of birth?”

- Orthodoxy

Monday, May 27, 2013

Chesterton shows up in Canada (faith doesn't)

There was a piece in a Canadian newspaper about people in Canada leaving organized religion, and especially Christianity. Some folks are going to other religions - Islam has doubled its numbers, for example. But a significant part of the population surveyed now identify themselves as having no religious affiliation.

The writer - Martin Wissmath - notes that the decision to leave faith and be unaffiliated has an effect on society and culture.

I think he's right, but it's not limited to Canada. Go to the movies, read a secular publication or book, watch television shows and news, or look at the decisions of government in the U.S. and Europe and you see signs of the waning of religion and desertion of Christian and moral values. Heck, a lesbian coming of age story involving scenes of graphic sex between a minor and an adult just won at Cannes.

Wissmath also points out that as people leave faith, it's not due to passion or thought.

"It's not so much an examined rejection of faith in favour of some other philosophical worldview, as a passive, fading, giving up. They just don't care anymore."

In grumpier moments I think it's not so much that people don't care, it's just that they don't care about anything that interferes with their own self fulfillment and gratification. They care about what feels good for themselves. Other things that require work - practicing religion, growing intellectually, being an informed citizen, etc. - are deemed not worth the effort.

Wissmath concludes by citing two great writers, one of them being, of course, G.K. Chesterton.

Since at least the 19th century Christianity has been waning in North America and Europe. With the exception of some years of resurgence, such as the 1950s, it's been a very gradual ebbing of the tide: the "melancholy, long, withdrawing roar," of the Sea of Faith that the poet Matthew Arnold predicted almost 250 years ago. But the shore of post-Christianity is emerging faster than ever.

The words of the early 20th century English journalist G.K. Chesterton come to mind as an apt description of the situation, even timelier now. He wrote, "the Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult, and left untried."

Indeed.

Friday, May 17, 2013

The Not Quite Great Gatsby

I went with some students and fellow teachers to see the new film version of The Great Gatsby.

There are some things to praise about the film, some to criticize. There are good moments and performances, but not enough to make it a great film or for me to heartily endorse it. In too much of it, flash and style take precedence over substance. And I'm not happy with some of the ways it strays from the novel.

But I began to wonder what Chesterton made of the novel when it came out.

I haven't found any comments by Chesterton about the book or even about F. Scott Fitzgerald yet - though they may be there (wiser and better-read Chestertonians may know of some).

But I have seen references to Fitzgerald - a fallen Catholic - being familiar with Chesterton's writings. There's even a post on this blog that predates my joining the team:

A collection of the letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald shows a number of references to Chesterton as the writer struggled in 1917 with his unsuccessful first draft of This Side of Paradise. He wrote Edmund Wilson that the novel "shows traces of Chesterton," and that he put "Barrie and Chesterton above anyone except Wells." Fitzgerald complained to biographer Shane Leslie of "gloomy, half-twilight realism," asking "Where are the novels of five years ago?" Fitzgerald included Chesterton's Manalive on his approved novel list, and also confided to Leslie that he was planning to quote some Chesterton gibberish on his new novel's title page ("Highty-ighty, tiddly-ighty, tiddley-ighty, ow!" from The Club of Queer Trades). [A Life in Letters, Edited by Mat-thew Bruccoli, Scribner's 1994, pp. 12-20] - Eric Scheske (July 28, 2005)

I'll keep searching,

.

Friday, May 10, 2013

A Benghazi Thought

“Men are ruled, at this minute by the clock, by liars who refuse them news, and by fools who cannot govern.” - GKC

I have been thinking about this week's Benghazi testimony. People died. Requests for help were not honored.

Meanwhile, Obama administration officials testified and gave speeches that were false. It's going to be hard to prove that people deliberately lied, but it's clear that the "truth" was shaped by the administration to suit its political ends.

Will anyone face charges? I seriously doubt it.

Will someone lose his or her job? Maybe - though some folks who have already left their jobs may serve as handy scapegoats.

Will political futures be affected? Perhaps. I think the odds of Hillary Clinton running for President in 2016 just grew longer. Of course, the average American voters - people of severely shallow thought and limited memory - may not even recall hearing about Benghazi by the time the 2016 primaries roll around. Heck, many will likely have forgotten whatchamacallit by the All Star break.

I'm not a supporter of the death penalty, but I'm tempted to think Chesterton may have had it right: “It is terrible to contemplate how few politicians are hanged. ”

Thursday, May 02, 2013

Live Action does it again

Live Action continues to expose the abortion industry. They view themselves as investigative journalists. I wonder how Chesterton, as a journalist, would have viewed their actions. He certainly would have agreed with their aims.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

On tap

“No animal ever invented anything as bad as drunkenness – or as good as drink.” – G.K. Chesterton

Tonight, I decided to have a beer. I don't know why; just in the mood.

As I sipped my Guinness Stout, I wondered if that was one of the beers Chesterton drank. Perhaps a scholar out there has studied the particular brands he drank. Perhaps a dedicated Chestertonian might then set a goal of drinking a pint of each brand the great one imbibed. I would be happy to volunteer.

Given GKC's distributist ideas, perhaps he preferred locally brewed beverages. Ales and porters of London and its environs? Hmm.

But perhaps he did sample a Guinness. I'll settle for that now.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

A Gosnell reflection

I don't know if late-term abortionist Kermit Gosnell

will end up in Hell,

but I bet he's hoping all those babies who died

won't be helping God to decide.

Friday, April 12, 2013

Today I wore Chesterton

I've also been wearing him on dress down days like today. Specifically, I have a Chesterton Academy sweatshirt. People assume it's a tribute just to Chesterton, not that it represents another high school. I don't explain. But I do proclaim.

Chesterton lives!

Thursday, April 04, 2013

In which I spout heresy

I've read a goodly amount of Chesterton's writings. My tally is no where near the amount the great Dale Ahlquist has read - I suspect he has studied even Chesterton's shopping lists ("Two cigars, three pieces of chalk, brown paper, ...") - but it's more than most people. I credit his biography of St. Francis with helping to save my faith, and I followed that up with such books as his biography of Aquinas, The Everlasting Man, and Orthodoxy, a slew of his essays, and a broad selection of his poetry.

But I had not read many of his Father Brown stories.

I had read a few of the Brown mysteries - the ones that are regularly anthologized - and I enjoyed them.

So this past Christmas I was delighted when youngest daughter gave me a first American edition of The Wisdom of Father Brown that she had found in a used bookstore.

I had a few other things to read first, then I got to this treasure full of anticipation.

With each story I grew more disappointed.

I am a fan of mysteries. I've read almost all the Sherlock Holmes tales, many of the Tony Hillerman Navajo stories, a number of Parker's Spenser books (where I learned a better way to cook pasta!), all the Father Dowling books my local library had, and I even got to interview the incredible (though sadly, now late) Ed Hoch, who's stories I love.

I just didn't think the mysteries in this Father Brown book were particularly good as mystery stories.

Then I got to "The God of the Gongs."

I was more than disappointed. I was offended.

I understand that it was a different time period and that racial names were viewed differently then, but I found the frequent use of "Nigger" jarring. If it had just been that - I've read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn - I could have understood the use of that word. But there was also an attitude of racial superiority that came through in various lines about Italians, darker races, and Blacks, and when Father Brown observed, "That negro who has just swaggered out is one of the most dangerous men on earth, for he has the brains of a European, with the instincts of a cannibal," I nearly threw the book down.

I don't think Chesterton was a racist. I think he was a product of his time.

I would not be surprised if such attitudes might be found in some of his other writings - I've only begun to mine the mother lode. But they have literary riches that outweigh such racial slag.

But as for the Father Brown tales ,,,

I'll finish reading the book - it was a gift and I feel obligated - but it may be a while before I'll read any more Father Brown mysteries. I've lost the desire.

Thursday, March 28, 2013

The Priest of Spring

In honor of the Triduum, an essay of Chesterton:

THE PRIEST OF SPRING

THE PRIEST OF SPRING

The sun has strengthened and the air softened just before Easter Day. But it is a troubled brightness which has a breath not only of novelty but of revolution, There are two great armies of the human intellect who will fight till the end on this vital point, whether Easter is to be congratulated on fitting in with the Spring - or the Spring on fitting in with Easter.

The only two things that can satisfy the soul are a person and a story; and even a story must be about a person. There are indeed very voluptuous appetites and enjoyments in mere abstractions like mathematics, logic, or chess. But these mere pleasures of the mind are like mere pleasures of the body. That is, they are mere pleasures, though they may be gigantic pleasures; they can never by a mere increase of themselves amount to happiness. A man just about to be hanged may enjoy his breakfast; especially if it be his favourite breakfast; and in the same way he may enjoy an argument with the chaplain about heresy, especially if it is his favourite heresy. But whether he can enjoy either of them does not depend on either of them; it depends upon his spiritual attitude towards a subsequent event. And that event is really interesting to the soul; because it is the end of a story and (as some hold) the end of a person.

Now it is this simple truth which, like many others, is too simple for our scientists to see. This is where they go wrong, not only about true religion, but about false religions too; so that their account of mythology is more mythical than the myth itself. I do not confine myself to saying that they are quite incorrect when they state (for instance) that Christ was a legend of dying and reviving vegetation, like Adonis or Persephone. I say that even if Adonis was a god of vegetation, they have got the whole notion of him wrong. Nobody, to begin with, is sufficiently interested in decaying vegetables, as such, to make any particular mystery or disguise about them; and certainly not enough to disguise them under the image of a very handsome young man, which is a vastly more interesting thing. If Adonis was connected with the fall of leaves in autumn and the return of flowers in spring, the process of thought was quite different. It is a process of thought which springs up spontaneously in all children and young artists; it springs up spontaneously in all healthy societies. It is very difficult to explain in a diseased society.

The brain of man is subject to short and strange snatches of sleep. A cloud seals the city of reason or rests upon the sea of imagination; a dream that darkens as much, whether it is a nightmare of atheism or a daydream of idolatry. And just as we have all sprung from sleep with a start and found ourselves saying some sentence that has no meaning, save in the mad tongues of the midnight; so the human mind starts from its trances of stupidity with some complete phrase upon its lips; a complete phrase which is a complete folly. Unfortunately it is not like the dream sentence, generally forgotten in the putting on of boots or the putting in of breakfast. This senseless aphorism, invented when man's mind was asleep, still hangs on his tongue and entangles all his relations to rational and daylight things. All our controversies are confused by certain kinds of phrases which are not merely untrue, but were always unmeaning; which are not merely inapplicable, but were always intrinsically useless. We recognise them wherever a man talks of "the survival of the fittest," meaning only the survival of the survivors; or wherever a man says that the rich "have a stake in the country," as if the poor could not suffer from misgovernment or military defeat; or where a man talks about "going on towards Progress," which only means going on towards going on; or when a man talks about "government by the wise few," as if they could be picked out by their pantaloons. "The wise few" must mean either the few whom the foolish think wise or the very foolish who think themselves wise.

There is one piece of nonsense that modern people still find themselves saying, even after they are more or less awake, by which I am particularly irritated. It arose in the popularised science of the nineteenth century, especially in connection with the study of myths and religions. The fragment of gibberish to which I refer generally takes the form of saying "This god or hero really represents the sun." Or "Apollo killing the Python MEANS that the summer drives out the winter." Or "The King dying in a western battle is a SYMBOL of the sun setting in the west." Now I should really have thought that even the skeptical professors, whose skulls are as shallow as frying-pans, might have reflected that human beings never think or feel like this. Consider what is involved in this supposition. It presumes that primitive man went out for a walk and saw with great interest a big burning spot on the sky. He then said to primitive woman, "My dear, we had better keep this quiet. We mustn't let it get about. The children and the slaves are so very sharp. They might discover the sun any day, unless we are very careful. So we won't call it 'the sun,' but I will draw a picture of a man killing a snake; and whenever I do that you will know what I mean. The sun doesn't look at all like a man killing a snake; so nobody can possibly know. It will be a little secret between us; and while the slaves and the children fancy I am quite excited with a grand tale of a writhing dragon and a wrestling demigod, I shall really MEAN this delicious little discovery, that there is a round yellow disc up in the air." One does not need to know much mythology to know that this is a myth. It is commonly called the Solar Myth.

Quite plainly, of course, the case was just the other way. The god was never a symbol or hieroglyph representing the sun. The sun was a hieroglyph representing the god. Primitive man (with whom my friend Dombey is no doubt well acquainted) went out with his head full of gods and heroes, because that is the chief use of having a head. Then he saw the sun in some glorious crisis of the dominance of noon on the distress of nightfall, and he said, "That is how the face of the god would shine when he had slain the dragon," or "That is how the whole world would bleed to westward, if the god were slain at last."

No human being was ever really so unnatural as to worship Nature. No man, however indulgent (as I am) to corpulency, ever worshipped a man as round as the sun or a woman as round as the moon. No man, however attracted to an artistic attenuation, ever really believed that the Dryad was as lean and stiff as the tree. We human beings have never worshipped Nature; and indeed, the reason is very simple. It is that all human beings are superhuman beings. We have printed our own image upon Nature, as God has printed His image upon us. We have told the enormous sun to stand still; we have fixed him on our shields, caring no more for a star than for a starfish. And when there were powers of Nature we could not for the time control, we have conceived great beings in human shape controlling them. Jupiter does not mean thunder. Thunder means the march and victory of Jupiter. Neptune does not mean the sea; the sea is his, and he made it. In other words, what the savage really said about the sea was, "Only my fetish Mumbo could raise such mountains out of mere water." What the savage really said about the sun was, "Only my great great-grandfather Jumbo could deserve such a blazing crown."

About all these myths my own position is utterly and even sadly simple. I say you cannot really understand any myths till you have found that one of them is not a myth. Turnip ghosts mean nothing if there are no real ghosts. Forged bank-notes mean nothing if there are no real bank-notes. Heathen gods mean nothing, and must always mean nothing, to those of us that deny the Christian God. When once a god is admitted, even a false god, the Cosmos begins to know its place: which is the second place. When once it is the real God the Cosmos falls down before Him, offering flowers in spring as flames in winter. "My love is like a red, red rose" does not mean that the poet is praising roses under the allegory of a young lady. "My love is an arbutus" does not mean that the author was a botanist so pleased with a particular arbutus tree that he said he loved it. "Who art the moon and regent of my sky" does not mean that Juliet invented Romeo to account for the roundness of the moon. "Christ is the Sun of Easter" does not mean that the worshipper is praising the sun under the emblem of Christ. Goddess or god can clothe themselves with the spring or summer; but the body is more than raiment. Religion takes almost disdainfully the dress of Nature; and indeed Christianity has done as well with the snows of Christmas as with the snow-drops of spring. And when I look across the sun-struck fields, I know in my inmost bones that my joy is not solely in the spring, for spring alone, being always returning, would be always sad. There is somebody or something walking there, to be crowned with flowers: and my pleasure is in some promise yet possible and in the resurrection of the dead.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Iron Maiden - Revelations

http://youtu.be/c5FKSu8MWW0

Amazing. The opening verse was taken from a G. K. Chesterton hymn.

I wonder how many other Chesterton works have inspired songs?

Where's my ukulele?

Pax et bonum

Saturday, March 16, 2013

Pope Francis and Chesterton

We keep learning more tidbits about Pope Francis,

who's been linked to soccer, subways, and dances,

but the best detail yet, when all is said and done,

is he's a fan of Chesterton.

(Per Mark Shea, apparently Pope Francis was on the board of the Argentinian Chesterton Society!)

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Pope Francis

I also thought it interesting that one commentator said if you want to understand Pope Francis, you should read Chesterton's St. Francis of Assisi.

I do wonder, though: Does he like a good beer? (I'd settle for a coffee drinker.)

Friday, March 08, 2013

Pope-u-lator

Just for the fun of it, give the pope-u-lator a try as we await the conclave. As folks at the site note, it's all tongue-in-cheek.

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Benedict XVI on Chesterton

In honor of our now former Pope Benedict, I post the following Zenit piece.

God be with Benedict.

By Paul De Maeyer

ROME, FEB. 7, 2012 (Zenit.org).- G.K. Chesterton and Benedict XVI have plenty in common, according to a professor of literature and Catholicism from the Pontifical Lateran University.

Andrea Monda will defend this perspective Saturday in Genoa at a conference titled "Common Sense Day. The Paradoxical Beauty of the Everyday. A Day for G.K. Chesterton."

Monda is set to close the event -- dedicated entirely to the English writer and thinker -- with a talk on "Good Sense, Good Life and Good Humor: G.K. Chesterton and Benedict XVI."

In the course of his presentation, Professor Monda will provide some excerpts from his next book, on the "Simple Virtues of Joseph Ratzinger," offering a "Chestertonian" reading of Benedict XVI's pontificate (Lindau Publishing House). The book is due out next month.

ZENIT spoke with the professor about his vision of the author and the Pontiff.

ZENIT: What relationship is there between Chesterton and Joseph Ratzinger?

Monda: Young Joseph Ratzinger read and appreciated several of Chesterton's books; in fact, here and there, whether before or after the papal election, direct or indirect quotations emerge of the work of the inventor of Father Brown. However, what I tried to do in the book, and what I will do in Genoa, is not so much a philological reconstruction of these quotations, but a little reasoning that develops from the two figures of the English thinker and the Bavarian theologian and Pontiff, on subjects which cut across the positions at the center of the attention of the congress' organizers: good sense, good life and good humor.

ZENIT: In the collective and media imagination, Pope Benedict XVI is not associated with humor, is this true?

Monda: The truth is that Ratzinger, just as every man, is a mystery, a complex reality often poorly rendered by the image that prevails in the mass media; it is from here that the need arose in me to write a book that gives greater weight and perspective to a picture that is otherwise trite, two-dimensional: the Pope of "no's," the German Pope staunch defender of the rigor of the moral norm. What is true in all of this is that Joseph Ratzinger is a serious person. However, be careful, says Chesterton, when he recalls, with his typical liking of paradoxes, that "serious is not the opposite of amusing, the opposite of amusing is not amusing, boring." Hence the Pope is a serious person, who takes seriously the Gospel and every man he meets, a serious person and, hence, also amusing, who knows the value of good humor, of humor and of smiling.

ZENIT: Is this liking for paradox the point of contact between Chesterton and Benedict XVI?

Monda: Yes and no. Certainly yes: being two persons of great acumen and intelligence, their reasoning is not trite but sparkling, at times unsettling, which also calls for flexibility in the intelligence of the interlocutor. In other words, they require appropriate interlocutors, equal to them. At the same time, Chesterton and the Pope are not two intellectuals merely content to give us paradoxical phrases, wit and puns. Their reasoning is ordered to create a dialogue, it is not fireworks but the desire to have a relationship with the other (even with the one who is distant, who does not believe, who is an "enemy" of the faith) without betraying adherence to their faith which, first of all, is lived, practiced and then preached.

ZENIT: What is the relationship between the two and good sense, good life and good humor?

Monda: This is what I will talk about at Genoa's congress. Connected between them are the three aspects and in all three one can almost see a similar behavior in the writer and the Pontiff. In regard to good sense: for Chesterton it is verifiable in children's fables whose "morals" are still valid today and he gives the example of Cinderella, which has the same meaning of the Magnificat of Luke's Gospel: "He has exalted the lowly." The English writer goes against the current in regard to modern and contemporary Western tendencies, which are maybe nice and respectable, which consider good sense as the overcoming of the world of childhood, full of unreal pleasant fantasies, to enter into the world of reason and hopefully of experimental science, seen as the only source of truth (but, unfortunately, not of meaning). Pope Ratzinger also goes against the current: for him good sense is what emerges from the Gospel and from the Christian faith and, also, in the paradox of giving one's life out of love. All this seems like a discordant voice, because the "tune" of modernity and of today's world has relegated Christianity to the same room of children's fables, an old and dusty place in which perhaps it was pleasing to be during childhood, but all together superfluous when one attains maturity and autonomy. In this connection, religion seems like an old superstition, an oppressive framework that constrains the free development of the mature, adult and emancipated person.

ZENIT: And in regard to the good life?

Monda: The above-mentioned depiction of Pope Ratzinger presents him as a sullen custodian of the truth, it portrays him as obsessed with the truth, as someone who uses truth as a club against freedom. Instead, the dialectical relation that is at the heart of the Pope is not that of truth/falsehood but that of joy/boredom. For Benedict XVI the good life, here as well, as in the case of good sense, is that which flows from adherence to the Gospel. And the same can be said of Chesterton. In both cases, the life that flows is thus "good," but it is not in fact tranquil but rather something like a battle. The good life is the profound desire that animates and stirs the heart of every man." "No matter what type of man he is," writes Chesterton, "he is not sufficient unto himself, whether in peace or in suffering. The whole movement of life is that of a man who seeks to reach some place and who fights against something." The Pope echoes him when he recalls that "only the infinite fills man's heart," to live well does not mean to be a "respectable" person, but it means to take up and receive life as an adventure. The good life is not an easy compromise, it is not to have found the formula to have everything at the same time in Western man's day, busy and marked by activism. No, the good life is to surrender to Christ, sign of contradiction. Born from this surrender is the life of faith as an adventure, as an encounter not with an idea, an ideological formula (which would be pure idolatry, state-latria or ego-latria in the end little changes) but an encounter with a person. Only an encounter with someone greater can make many happy.

ZENIT: In short, good humor, perhaps the humor of the Englishman Chesterton is the same as the German Pope's?

Monda: Yes, from a certain point of view, because in both cases humor thrusts its roots in humility. Is it not the case that also at the etymological level the two words are born from humus, earth? He is well-grounded, who does not raise himself in pride, at the same time is gifted with humor, because he knows irony and self-irony, because he perceives, perhaps in a confused way, that a larger world exists beyond his own "I" and, beyond this world, Someone who is still greater. From this point of view, the modern world offers disturbing signs because there is no longer good humor but anger, there is no irony but sarcasm, there is no sentiment but resentment. However, a society that loses the sense of humor, recalled Maritain, is preparing for its funeral.

In different times and ways, Chesterton and Ratzinger cry out however against this madness that envelops the life of Western men and remind all that there is a possibility for joy, not for pleasure, which is always less than man and under his control, but for joy, which is always a great mystery. Joy, Chesterton wrote in the last page of his masterpiece Orthodoxy: "is the gigantic secret of Christianity." And it is also the secret of Benedict XVI who, with his timid and awkward but firm and patient smile, with the strength of an ordered, clear, honest, quiet intelligence, and with the energy of a faith lived without frills with the abandon of a child, challenges every day the temptations of men, his contemporaries, towards laziness and short cuts, towards ideologies and idolatries which are always renewed in a heart that lives in bad humor and resentment. From this point of view Benedict XVI can be described as the Pope of joy, perhaps the most recurrent word in his addresses since he was elected, because, as he said in the recent book-interview Light of the World; "All my life has been suffused by a guiding thread: Christianity gives joy, it widens the horizons." Here, in one phrase is the whole of Ratzinger and, if we think correctly, the whole of Chesterton. Faith, joy, reason. Good sense, good life, good humor.

God be with Benedict.

By Paul De Maeyer

ROME, FEB. 7, 2012 (Zenit.org).- G.K. Chesterton and Benedict XVI have plenty in common, according to a professor of literature and Catholicism from the Pontifical Lateran University.

Andrea Monda will defend this perspective Saturday in Genoa at a conference titled "Common Sense Day. The Paradoxical Beauty of the Everyday. A Day for G.K. Chesterton."

Monda is set to close the event -- dedicated entirely to the English writer and thinker -- with a talk on "Good Sense, Good Life and Good Humor: G.K. Chesterton and Benedict XVI."

In the course of his presentation, Professor Monda will provide some excerpts from his next book, on the "Simple Virtues of Joseph Ratzinger," offering a "Chestertonian" reading of Benedict XVI's pontificate (Lindau Publishing House). The book is due out next month.

ZENIT spoke with the professor about his vision of the author and the Pontiff.

ZENIT: What relationship is there between Chesterton and Joseph Ratzinger?