Tuesday, February 28, 2006

A Plug for Belloc

"Today Belloc remains a writer who has not been tried and found wanting, but who has simply not been tried at all."

Frederick Wilhelmson, Hilaire Belloc: No Alienated Man

Monday, February 27, 2006

The Coloured Lands - Third Sortie

A little boy once looked over the garden fence and saw four knights with enormous crests riding by. As he is now married to a princess and moves in rather good society, he has desired me not to mention his name: so we will call him Redlegs. Being interested in such things he climbed over the fence and ran after the knights to see where they were going. They came to a very old man, who was sitting on the very sharp point of a rock, balancing himself. The knights, seeing by his sugar-loaf hat and white beard that he was a Magician, asked him where they could find the Princess Japonica (for so the Princess, who is a relative of mine, desires to be described). "The Princess Japonica," replied the Magician, "lives in the Castle beyond the Last Wood in the World, in the place where it is always sunset. She cannot come and visit anyone, and no one can visit her, because there are only two roads to it: and the right hand road is held by a Giant with One Head, and the left hand road is held by a Giant with Two Heads." Then the first knight said with great excitement (he was Bromley Smunk on the mother's side, and you know what they are), "I will soon clear the giant out of the way. But I think I will confine myself to the giant with one head. For I am a humane man and desire to cut off as few heads as possible."

So the first knight set out along the road to the One-Headed Giant. And a little while after the second knight set out & then the third & then the fourth, all the same way. The little boy stopped behind and talked to the Magician about the Fiscal Question. Scarcely had they dismissed this brief topic, then they saw a sad string of people coming along the road from the One-Headed Giant. They were the four knights & and I am sorry to say that they were rather smashed. Then Redlegs said suddenly, "I should very much like to see a Two-Headed Giant. Lend me a sword." Then they all roared with laughter and told him how silly he was to think that he could kill the Two-Headed Giant when they couldn't kill even the One-Headed Giant. But he went off all the same, with his head in the air & he found the Two-Headed Giant on the great hills where it is always sunset. And then he found out a funny thing. The Two-Headed Giant did not rush at him and tear him to pieces as he had expected.

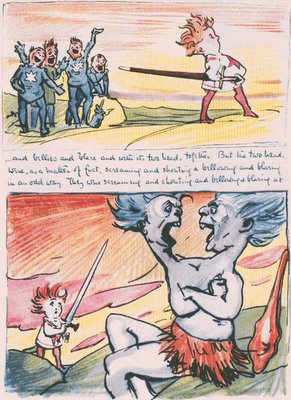

It did certainly scream & shout and bellow and blare and with its two heads together. But the two heads were, as a matter of fact, screaming and shouting & bellowing and blaring in an odd way. They were screaming and shouting and bellowing & blaring at each other. One head said, "You are a Pro-Boer": the other said, with bitter humour, "You're another"; in fact, the argument might have gone on for ever, growing more savage & brilliant every moment, but it was cut short by Redlegs, who took out the great sword he had borrowed from one of the knights & poked it sharpley into the giant & killed him. The huge creature sprawled & writhed for a moment in death & said "You are beneath my notice." Then it died happily.

Redlegs went on along the road that had been guarded by the Two-Headed Giant, until he came to the Castle of the Princess. After a few words of explanation, I need hardly say they were married - and lived happily ever after. The Magician, who gave the bride away, said after the conclusion of the ceremony the following cabalistic and totally unintelligible words: "My son, the Giant who had one head was stronger than the Giant who had two. When you grow up there will come to you other magicians who will say, '[Something in Greek; I don't have the font for it, and don't know what it says anyway]. Examine your soul, wretched kid. Cultivate a sense of the differentiations possible in a single psychology. Have nineteen religions suitable to different moods.' My son, these will be wicked magicians; they will want to turn you into a two-headed giant." Redlegs did not know what this meant and nor do I.

===

That's that. I'm not sure what we'll get next time, but there's still a great deal to address. We might, for a lark, take a look at the illustrated demonology he constructed at the age of 17.

Better a Lender Than a Borrower Be

Here is an excerpt:

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, what is plagiarism? The least sincere form? A genuine crime? Or merely the work of someone with less-than-complete mastery of quotation marks who is in too great a hurry to come up with words and ideas of his own?Read the full article by Joseph Epstein at The Weekly Standard (03/06/2006, Volume 011, Issue 24).

Over many decades of scribbling, I have on a few occasions been told that some writer, even less original than I, had lifted a phrase or an idea of mine without attribution. I generally took this as a mild compliment. Now, though, at long last, someone has plagiarized me, straight out and without doubt. The theft is from an article of mine about Max Beerbohm, the English comic writer, written in the pages of the august journal you are now reading.

The man did it from a great distance--from India, in fact, in a publication calling itself "India's Number One English Hindi news source"; the name of the plagiarist is being withheld to protect the guilty. I learned about it from an email sent to me by a generous reader.

...

In the realm of plagiarism, my view is, better a lender than a borrower be. (You can quote me on that.) The man who reported the plagiarism to me noted that he wrote to the plagiarist about it but had no response. At first I thought I might write to him myself, remarking that I much enjoyed his piece on Max Beerbohm and wondering where he found that perfectly apposite G.K. Chesterton quotation. Or I could directly accuse him, in my best high moral dudgeon, of stealing my words and then close by writing--no attribution here to Rudyard Kipling, of course--"Gunga Din, I'm a better man than you." Or I could turn the case over, on a contingency basis, to a hungry young Indian lawyer, and watch him fight it out in the courts of Bombay or Calcutta, which is likely to produce a story that would make Bleak House look like Goodnight Moon.

Sunday, February 26, 2006

Art for Art's Sake

I don’t know much about art, so I can’t do much besides scoff. But I did dig up a few Chesterton quotes that seem apt:

“Art, like morality, consists in drawing the line somewhere.”

“This bias against morality among the modern aesthetes is . . . not really a bias against morality; it is a bias against other people’s morality.”

Thanks, TDE.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

Friday, February 24, 2006

New York Treat

Last Friday Before Lent: Feeling Thirsty?

"November 30, 1929 issue of the London Illustrated News. Has a full page article by G.K. Chesterton, a full page Guinness Beer ad, a full page of illustrations (3 pictures) of the Mammoth of Moravia, a full page of illustrations and text on using paraffin in taxidermy etc etc." (link)

Seriously Good News

Barron suggests that we resolve to read a "serious" book this year: "perhaps a classic such as St. Augustine’s Confessions or Thomas Merton’s Seven Story Mountain. Make an effort this year to delve into a great Catholic literary master such as Dante, G.K. Chesterton or Flannery O’Connor. Or study the paintings of Caravaggio and Michelangelo, and the sculptures and architecture of Bernini. Enter into the prayerful reading of the Bible."

The idea of reading a "serious" book might sound dreadful. But Chesterton reminds us that "serious" is not the opposite of "funny" ... "Funny is the opposite of not funny, and of nothing else." (Heretics, XVI. On Mr. McCabe and a Divine Frivolity)

Thursday, February 23, 2006

Don't Miss: To A Modern Poet

Same Stories, Different Decade

“News is old things happening to new people.”read the entire article by Jim Hillibish in the Canton Repository (February 18, 2006)

Newspaperman Malcolm Muggeridge penned this warning to self-assured newsmakers who ignore history and believe they are unique for their times.

A friend of mine offered evidence of this in a flat box of yellowed newsprint she found in her grandfather’s attic, proof there’s nothing new on our favorite planet.

Inside were Puck tabloids, named for Shakespeare’s meddling sprite in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Joseph Keppler in 1871 converted mischief into cartoons and stories in his national weekly, inventing the first political humor magazine.

I realized the genius of Muggeridge while working my way through this pile of musty mirth. They had terrorist bombers, assassins, religious and political fanatics and legions of officious folks trying to tell everybody how to think, disguised as special interests.

Politicians were bought with “campaign contributions,” responded to accusations with “lies of convenience” and created political parties threatening “free thinking among an endangered species — the voter.”

Americans were worried sick about their jobs going overseas. Instead of Microsoft and Wal-Mart, the monopolists of the telegraph and railroads were the fat cats draining us poor citizens of scarce dollars. So were usurious credit companies. So was religion.

“Kissing pastors who make love to the funds of the church have palled upon our taste.”

Sound familiar?

The only difference was the Democrats were conservative leg draggers and the Republicans were liberal buffoons, roles reversed today. Puck lambasted both sides with words mightier than swords.

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Chesterton is EVERYWHERE

And no, I didn't run across it as part of my regular morning stimulation. I heard about it here, then checked it out myself. If you want to check out the GKC quote and the girls, go to that link. It has a link to the girlie site.

Here's the quote:

"There are no wise few. Every aristocracy that has ever existed has behaved, in all essential points, exactly like a small mob." "Heretics", 1905

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

GKC and Porn

"All healthy men, ancient and modern, know there is a certain fury in sex that we cannot afford to inflame, and that a certain mystery and awe must ever surround it if we are to remain sane.”

When author G.K. Chesterton wrote these words nearly a century ago, he couldn’t have comprehended the fury pornography had yet to unleash on society.

A $57-billion worldwide industry, pornography is no secret pastime. It’s an epidemic infecting far more than the sole viewer, according to experts who say spouses, children, health, employment and good standing in society are often contaminated too.

Monday, February 20, 2006

More from The Coloured Lands

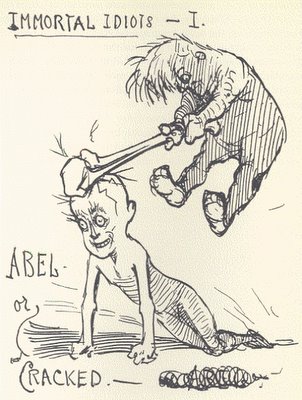

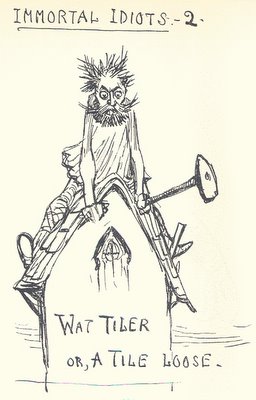

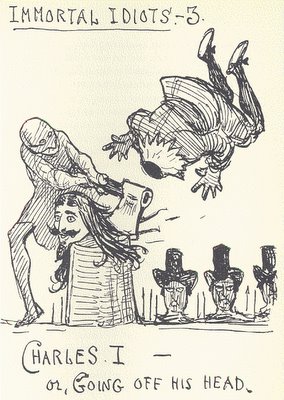

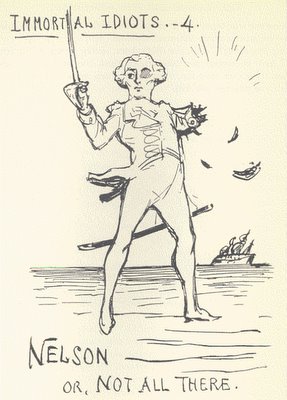

Of the four, Charles II is my favourite artistically, and Abel thematically. Also, for those of you unfamiliar with Wat Tiler, he was, along with Jack Straw, the leader of a peasant rebellion against Richard II in 1381. The rebellion faltered when the army was overcome by Richard II's charm. Tiler himself was killed in a fight with the mayor of London soon after. The Nelson one, regrettably, leaves me kind of flat, but that's mostly due to my radical bias in favour of the man.

Of the four, Charles II is my favourite artistically, and Abel thematically. Also, for those of you unfamiliar with Wat Tiler, he was, along with Jack Straw, the leader of a peasant rebellion against Richard II in 1381. The rebellion faltered when the army was overcome by Richard II's charm. Tiler himself was killed in a fight with the mayor of London soon after. The Nelson one, regrettably, leaves me kind of flat, but that's mostly due to my radical bias in favour of the man.Anyhow, some text...

Paints in a Paint-Box

By G.K. Chesterton

There has often arisen before my mind the image of an individual who should collect with laborious care articles which no other person valued and make an exhaustive classification of things which everyone else regarded as insignificant and inane. This being might have a magnificent and futile pre-eminence in many enterprises. He might have the finest collection of disused cigar ends in the world. He might accumulate pipe ashes and the parings of lead pencils with an enthusiasm and a poetry worthy of a better cause. He might, if he were a millionaire, carry this immense crusade into even larger matters. He might build great museums in which nothing was exhibited except lost umbrellas and bad pennies. He might found important papers and magazines in which nothing was recorded except unimportant things; in which stunning head lines announced the loss of three burnt matches out of an ash tray and long and philosophical leading articles were devoted to such questions as the Christian names of the Fulham omnibus conductors, or the number of green window-blinds in the Harrow Road. If a man did seriously devote himself to these inanities he would unquestionably be the object of a great deal of derision. Nevertheless, if he chose to turn round upon us and defend his position, we should suddenly realise that our whole civilisation was as moonstruck as his hobby. He would say with truth that there was, philosophically speaking, as much to be said for collecting the ferrules of gentlemen's umbrellas as for collecting books or banknotes.

For all essential purposes there is no reason which can be offered for the preference which mankind exhibits for one material rather than another. It is impossible to suggest a single valid reason why gold should be more expensive than a genuinely rich red mud. It is impossible to say why a precious stone should be more valued than a copying-ink pencil or an old green bottle, which are both more useful and more picturesque. Almost all the theories which profess to explain this paradox from the metaphysical point of view have failed entirely. It is commonly said, for example, that materials are valued on account of their rarity. Clearly, however, this cannot be maintained. There are a great many things more rare than gold and silver; however small may be the chances for any one of us of picking up half-a-sovereign in the gutter, the chances that we should pick up a latch-key tied up with red ribbon, or a copy of The Times descriptive of the introduction of the first Home Rule Bill, are even less. Yet people do not make a private museum of latch-keys with red ribbons or boast of a unique collection of copies of The Times for that particular date in 1885.

Those who speak of rarity as the essence of value seem scarcely to realise how prodigious are the consequences of their view. The things in this world which are thoroughly insignificant are precisely the things which are singularly rare. It is very rare for a solicitor with a red moustache born in Devonshire to lend 1s. 6d. to the nephew of a Scotch cloth-merchant residing in Clement's Inn; such a thing perhaps has only happened once, if at all; yet we do not write the incident in letters of gold, or attach any particular importance to any incidentals, rags or relics, which may have been found to be commemorative of the spot where it occurred. Mere rarity certainly is not the test of value. if it were so, gold would be less valuable than many varieties of street mud, and beautiful things upon the whole much less valuable than ugly ones. The fact of the matter is, that mankind has selected certain unmeaning objects as things of value without either intrinsic or comparative criticism. It has made one material infinitely more valuable than another material by a mere process of selecting one kind of mud from another. In many respects the current conception of the substance which is valuable is decidedly an inferior one. Value, for example, almost entirely centres around metals, which are the dullest and most uncommunicative, the most material, of all earthly things. They belong to the mineral creation, which is the very canaille of the cosmic order. It is extraordinary when one comes to think of it that so thoroughly base a thing as gold metal should be the form in which all our most human and humanising tendencies are bound up. Whenever we apply for payment in cash, we fulfill almost to the point of detail the word of the parable, we ask for bread and we receive a stone.

Again, the theory that materials are valued on account of their beauty will not support criticism. There are a great many objects which are more beautiful than precious objects. Peacocks' feathers are more beautiful, and autumn leaves and split firewood and clean copper. Nevertheless, it has not occurred to any person to swagger in a purse-proud manner over his possession of firewood or to cling to every advantage which could be founded upon copper. The miser who should spend a laborious life in hoarding and counting the autumn leaves has, I think, yet to be born.

Substances have, however, a real intrinsic spirituality. Materials are not likely to be despised except by materialists. Children, for example, are fully conscious of a certain mystical, and yet practical, quality in the things they handle; they love the essential quality of an object chivalrously, and for its own sake. A child has an ingrained fancy for coal, not for the gross materialistic reason that it builds up fires by which we cook and are warmed, but for the infinitely nobler and more abstract reason that it blacks his fingers. In almost all the old primitive literatures we find the presence of this splendid love of materials for their own sake. We find no delicate and cunning combinations of colour, such as those which are the essence of our latter-day art, but we find a gigantic appetite for materials linked with their own natural characteristics, for red gold, and green grass; not the taste for green gold and red grass which marks so much contemporary literature. They did not require either contrast or harmony to tickle their aesthetic hunger. They loved the redness of wine or the white splendour of the sword in all their virginity and loveliness, a single splash of crimson or silver upon the black background of old Night.

The poetry of substances exists, and it takes no account of the ordinary codes of value. Gold is certainly a less fascinating substance than silver. And even silver is to the spirit which retains its childhood less fascinating than lead. Lead is a truly epic substance; it contains every quality that could be required for that purpose. In colour it is the most delicate tint of dimmed silver, a kind of metallic splendour under a perpetual cloud; in consistency again it unites two of the antagonistic and indispensable elements of a fascinating substance. It is at once robust and malleable, it bends and it resists; we have the same feeling towards a stiff layer of lead that we have towards destiny. It is stiff, yet it yields sufficiently to make us fancy that it might yield altogether. Another substance which presents in a somewhat different way the same contradiction is common wood. It is the most fascinating and the most symbolic of substances, since it has just enough essential toughness to resist the amateur, and just enough pliability to become like a musical instrument in the hands of the expert. Working in wood is the supreme example of creation; creation in a material which resists just enough and not an iota too much. It was surely no wonder that the greatest who ever wore the form of man was a carpenter.

There remains one definite order of materials which have to the imaginative eye far more essential value than any jewels. All pigments and colour materials have one supreme advantage over mere diamonds and amethysts. They are, so to speak, ancestors as well as descendants; they propagate an infinite progeny of images and ideas. If we look at a solid bar of blue chalk we do not see a thing merely mechanical and final. We see bound up in that blue column a whole fairyland of potential pictures and tales. No other material object gives us this sense of multiplying itself. If we leave a cigar in a corner we do not expect that we shall find it the next day surrounded by a family of cigarettes. A diamond ring does not contribute in any way to the production of innumerable necklaces and bracelets. But the chalks in a box, or the paints in a paint-box, do actually embrace in themselves an infinity of new possibilities. A cake of Prussian Blue contains all the sea stories in the world, a cake of emerald green encloses a hundred meadows, a cake of crimson is compounded of forgotten sunsets.

Some day, for all we know, this eternal metaphysical value in chalks and paints may be recognized as of monetary value; men will proudly show a cake of chrome yellow in their rings, and a cake of ultramarine in their scarf pins. There is no saying what wild fashions the changes of time may make; a century may find us economising in pebbles and collecting straws. But whatever may come, the essential ground of this habit will remain the same as the essential ground of all the religions, that we can only take a sample of the universe, and that that sample, even if it be a handful of dust (which is also a beautiful substance), will always assert the magic of itself, and hint at the magic of all things.

==

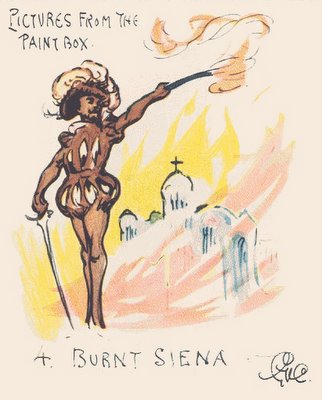

Well, that's quite a mouthful. In our next installment (which may come sometime mid-week), we will see some of the illustrations that were produced to accompany "Paints in a Paint-Box," as well, perhaps, as something else (note: the "Burnt Siena" image from the last Coloured Lands update was from this story). There's a good series of self-deprecating caricatures that Gilbert produced of himself that will definitely prove worthwhile, as well as a story that is told purely in illustration and drawn text. I will, of course, provide a transcription of that text for the hard of vision.

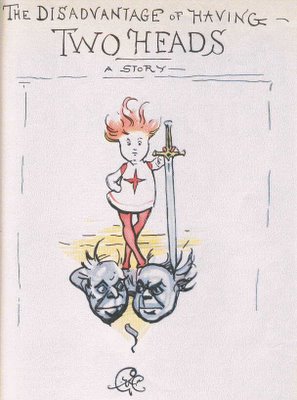

Be sure to let any Chestertonians you know what's going on here. The Coloured Lands only had very few editions, and it's rare indeed that anyone ever sees it. You will definitely want to be on hand for the transcription of the gloriously-illustrated fable, "The Disadvantage of Having Two Heads: A Story." All this and more as the days go by.

Friday, February 17, 2006

GKC in IT Week

G. K. Chesterton once wrote that the reason Christianity was declining was ‘not because it has been tried and found wanting, but because it has been found difficult and therefore not tried’. So too with time management. There is no magic formula and circumstances – and interruptions – often seem to conspire to prevent best intentions from working out. Some people, perhaps failing to achieve what they want, despair and give up.You can read the entire article Get Tougher With Time here.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Some scans from The Coloured Lands

And we shall round it out with one of his darling caricatures of rage:

Next time there will be some more text from the book, as well as a caricature series entitled "Immortal Idiots" in which such characters as Abel, Charles I, and Horatio Nelson meet their doom.

Next time there will be some more text from the book, as well as a caricature series entitled "Immortal Idiots" in which such characters as Abel, Charles I, and Horatio Nelson meet their doom.

Sassoon: Friend of Belloc

Siegfried Sassoon was a septuagenarian when he was received into the Catholic Church in 1957. An early and lasting admiration for Belloc and a late friendship with Ronald Knox were both significant factors in his spiritual journey, but most important was his own introspective mysticism. His final acceptance of Christianity was the culmination of a lifetime’s search, traceable through his poetry back to his youth.

A Prayer in Old Age

Being no expectance of heaven unearned

No hunger for beatitude to be

Until the lesson of my life is learned

Through what Thou didst for me.

Bring no assurance of redeemed rest

No intimation of awarded grace

Only contrition, cleavingly confessed

To Thy forgiving face.

I ask one world of everlasting loss

In all I am, that other world to win.

My nothingness must kneel below Thy Cross.

There let new life begin.

Click here to read the entire article, Well Versed In Faith, at IgnatiusInsight.com.

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

Max's Favorite

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Fr. Brown Book

To be honest, I'm not a big fan of mystery stories and, in fact, other than Fr. Brown stories and the talented John Peterson's excellent short stories in Gilbert Magazine, I never read 'em. I have read "The Blue Cross," though, and I trust Ms. Brown to produce a good read. This is tempting.

"G. K. Chesterton was one of the greatest Catholic writers of the 20th century, and more and more people today are discovering the treasure in his works. This guide focuses on the very first "Father Brown Mystery" that he wrote.

"Mrs. Brown has written a comprehensive study guide with vocabulary, discussion questions, and word study. Your student will find much food for thought while becoming acquainted with this great writer.

"The study guide includes the complete text of the story along with illustrations by Sean Fitzpatrick."

Link.

Monday, February 13, 2006

Great news

Yes, my copy of Chesterton's The Coloured Lands arrived in the mail yesterday, in all its colourful glory. Contained within are rare essays, poems and images produced by Chesterton at various stages of his life, and collected into a single volume by his biographer, Maisie Ward. The most thrilling gems in this gaudy crown include several coloured plates produced merely as an excuse to use a certain colour (such as "Prussian Blue" and "Burnt Siena"). More intriguing still is a lengthy illustrated demonology that Chesterton wrote at the age of 17.

We shall see much of these as time passes (including scans of the artwork), but we will not take the book in order. For now, we shall merely bear witness to a short tale which may prove appropriate for the morrow - St. Valentine's Day.

The Whale's Wooing

By G.K. Chesterton

A newspaper famous for its urgency about practical and pressing affairs recently filled a large part of its space with the headline, "Do Whales Have Two Wives?" There was a second headline saying that Science was about to investigate the matter in a highly exact and scientific fashion. And indeed it may be hoped that science is more exact than journalism. One peculiarity of that sentence is that it really says almost the opposite of what it intended to say. We might suppose that, before printing a short phrase in large letters, a man might at least look at it to see whether it said what he meant. But behind all this hustle there is not only carelessness but a great weariness. Strictly speaking, the phrase, "Do Whales Have Two Wives?" could only mean, if it meant anything, "Do all whales, in their collective capacity, have only two wives between them?" But the journalist did not mean to suggest this extreme practice of polyandry. He only meant to ask whether the individual whale can be reproached with the practice of bigamy. At first sight there is something rather quaint and alluring about the notion of watching a whale to see whether he lives a double life. A whale scarcely seems designed for secrecy or for shy and furtive flirtation. The thought of a whale assuming various disguises, designed to make him inconspicuous among other fishes, puts rather a strain on the imagination. He would have to keep his two establishments, one at the North Pole and the other at the South, if his two wives were likely to be jealous of each other; and if he really wished to becoming a bone (or whale-bone) of contention. In truth the most frivolous philanderer would hardly wish to conduct his frivolities on quite so large a scale; and the loves of the whales may well appear a theme for a bolder pen than any that has yet traced the tremendous epic of the loves of the giants.

But we have a sort of fancy or faint suspicion about where it may end. Science, or what journalism calls Science, is always up to its little games; and this might possibly be one of them. We know how some people perpetually preach to us that there is no morality in nature and therefore nothing natural in morality. We know that we have been told to learn everything from the herd instinct or the law of the jungle; to learn our manners from a monkey-house and morals from a dog-fight. May we not find a model in a far more impressive and serene animal? Shall we not be told that Leviathan refuses to put forth his nose to the hook of monogamy, and laughs at the shaking of the chivalric spear? To the supine and superstitious person, who has lingered with one wife for a whole lifetime, will not the rebuke be uttered in ancient words; "Go to the whale, thou sluggard." Contemplating the cetaceous experiments in polygamy, will not the moralist exclaim once more: "How doth the little busy whale improve the shining hour!" Will not the way of this superior mammal be a new argument for the cult of the new Cupid; the sort of Cupid who likes to have two strings to his bow? For we are bound to regard the monster as a moral superior, according to the current moral judgments. We are perpetually told that the human being is small, that even the earth itself is small, compared with the splendid size of the solar system. If we are to surrender to the size of the world, why not to the size of the whale? If we are to bow down before planets which are large than our own, why not before animals that are larger than ourselves? Why not, with a yet more graceful bow, yield the pas (if the phrase be sufficiently aquatic) to the great mountain of blubber? In many ways, he looks very like the highest moral ideal of our time.

Saturday, February 11, 2006

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Free Prize Inside!

Thanks to Cruz y Fierro for finding this.

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

GKC is Everywhere: Sighting in New York

"G. K. Chesterton said that it was much braver to drop in on your neighbour unannounced than it was to go on a round-the-world trip. That's sort of the principle behind this collection of essays about New York by Ian Frazier, a long-time contributor to The New Yorker, who moved to the city in the early 1970s from small-town Ohio.

"Frazier's version of the Chesterton line is that you get a much sharper view of New York by looking at the tiny, everyday, dreary things that go on unremarked in the city than you would by, say, climbing the Empire State Building and having a Martini with Rudy Giuliani and Frank Sinatra."

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

More GKC Friends in the Blogosphere

Today's sample:

"'It would be much truer to say that a man will certainly fail, because he believes in himself. Complete self-confidence is not merely a sin; complete self-confidence is a weakness.'

"Chesterton used the words just mentioned to illustrate the claim with which he opened the chapter. "Thoroughly worldly people," he claimed, "never understand even the world; they rely altogether on a few cynical maxims, which are not true." Indeed, our sarcastically honest social commentator was right!

"Some people just didn't understand the most basic reason for man's existence and progress: God willed it an allows it to happen. Nothing is or happens apart from God, regardless of how much one man believes in himself. Sadly, Chesterton's message was not heeded by many. Far too few men and women in the 21st century acknowledge that we need more to survive than simply our own faculties."

Musings from Memphis.

Monday, February 06, 2006

Chesterton on Islam

However, we can not expect too much of people. The first time is always a sting.

Chesterton had some things to say about Islam, as he had things to say about everything, and much of it is both profound and prescient.

First, with regard to the situation at hand:

"...a man preaching what he thinks is a platitude is far more intolerant than a man preaching what he admits is a paradox. It was exactly because it seemed self-evident, to Moslems as to Bolshevists, that their simple creed was suited to everybody, that they wished in that particular sweeping fashion to impose it on everybody. It was because Islam was broad that Moslems were narrow. And because it was not a hard religion it was a heavy rule. Because it was without a self-correcting complexity, it allowed of those simple and masculine but mostly rather dangerous appetites that show themselves in a chieftain or a lord. As it had the simplest sort of religion, monotheism, so it had the simplest sort of government, monarchy. There was exactly the same direct spirit in its despotism as in its deism. The Code, the Common Law, the give and take of charters and chivalric vows, did not grow in that golden desert. The great sun was in the sky and the great Saladin was in his tent, and he must be obeyed unless he were assassinated. Those who complain of our creeds as elaborate often forget that the elaborate Western creeds have produced the elaborate Western constitutions; and that they are elaborate because they are emancipated." ("The Fall of Chivalry," The New Jerusalem)

"There is in Islam a paradox which is perhaps a permanent menace. The great creed born in the desert creates a kind of ecstasy out of the very emptiness of its own land, and even, one may say, out of the emptiness of its own theology. It affirms, with no little sublimity, something that is not merely the singleness but rather the solitude of God. There is the same extreme simplification in the solitary figure of the Prophet; and yet this isolation perpetually reacts into its own opposite. A void is made in the heart of Islam which has to be filled up again and again by a mere repetition of the revolution that founded it. There are no sacraments; the only thing that can happen is a sort of apocalypse, as unique as the end of the world; so the apocalypse can only be repeated and the world end again and again. There are no priests; and yet this equality can only breed a multitude of lawless prophets almost as numerous as priests. The very dogma that there is only one Mahomet produces an endless procession of Mahomets. Of these the mightiest in modern times were the man whose name was Ahmed, and whose more famous title was the Mahdi; and his more ferocious successor Abdullahi, who was generally known as the Khalifa. These great fanatics, or great creators of fanaticism, succeeded in making a militarism almost as famous and formidable as that of the Turkish Empire on whose frontiers it hovered, and in spreading a reign of terror such as can seldom be organised except by civilisation…" (Lord Kitchener)

"I do not know much about Mohammed or Mohammedanism. I do not take the Koran to bed with me every night. But, if I did on some one particular night, there is one sense at least in which I know what I should not find there. I apprehend that I should not find the work abounding in strong encouragements to the worship of idols; that the praises of polytheism would not be loudly sung; that the character of Mohammed would not be subjected to anything resembling hatred and derision; and that the great modern doctrine of the unimportance of religion would not be needlessly emphasised." (ILN Nov. 15, 1913)

"A good Moslem king was one who was strict in religion, valiant in battle, just in giving judgment among his people, but not one who had the slightest objection in international matters to removing his neighbour's landmark." (ILN Nov. 4, 1911)

The analysis of For Four Guilds approaches; I've been caught up in other things, however, and it has been tragically delayed. This, however, should suffice for now.

American Book Review: 100 Best First Lines From Novels

47. There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it. — C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952)

63. The human race, to which so many of my readers belong, has been playing at children's games from the beginning, and will probably do it till the end, which is a nuisance for the few people who grow up. — G. K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904)

Happily, my personal favorite first line (though not a Chesterton line) made the list:

70. Francis Marion Tarwater's uncle had been dead for only half a day when the boy got too drunk to finish digging his grave and a Negro named Buford Munson, who had come to get a jug filled, had to finish it and drag the body from the breakfast table where it was still sitting and bury it in a decent and Christian way, with the sign of its Saviour at the head of the grave and enough dirt on top to keep the dogs from digging it up. — Flannery O'Connor, The Violent Bear it Away (1960)

Friday, February 03, 2006

Out of This Perpetual Dog-Fight

"You modify one another's thought; out of this perpetual dog-fight a community of mind and a deep affection emerge." That is what C.S. Lewis said about his enduring friendship with Owen Barfield, who greatly influenced his bedrock views on imagination and myth.link to the entire article by Colin Duriez, "The Way of Friendship" at Christian History & Biography

...

Rather like the texts of literature, a friend provides another vantage point from which to view the world. For Lewis, his different friends opened up reality in varying ways. Owen Barfield, for instance, was very different from Arthur Greeves, who had revealed to Lewis he was not alone in the world. Though Barfield shared with Lewis a view of what was important, and asked strikingly similar questions, the conclusions he came to usually differed radically from those of Lewis. Throughout the 1920s, the two had waged what Lewis called a "Great War," a long dispute over the kind of knowledge that imagination can give. As Lewis put it, it was as if Barfield spoke his language but mispronounced it.

Lewis's friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien, like that with Barfield, was based upon irreducible differences as well as likenesses. Initially, the two were drawn together by a love of myth, fairytale, and saga, a bond that deepened when Lewis became a Christian. There were emerging differences of temperament, churchmanship, and storytelling style, however, which strained yet enriched the friendship.

Thursday, February 02, 2006

For Four Guilds: The Bell-Ringers

IV: The Bell-Ringers

The angels are singling like birds in a tree

In the organ of good St. Cecily:

And the parson reads with his hand upon

The graven eagle of great St. John:

But never the fluted pipes shall go

Like the fifes of an army all a-row,

Merrily marching down the street

To the marts where the busy and idle meet;

And never the brazen bird shall fly

Out of the window and into the sky,

Till men in cities and shires and ships

Look up at the living Apocalypse.

But all can hark at the dark of even

The bells that bay like the hounds of heaven,

Tolling and telling that over and under,

In the ways of the air like a wandering thunder,

The hunt is up over hills untrod:

For the wind is the way of the dogs of God:

From the tyrant's tower to the outlaw's den

Hunting the souls of the sons of men.

Ruler and robber and pedlar and peer,

Who will not hearken and yet will hear;

Filling men's heads with the hurry and hum

Making them welcome before they come.

And we poor men stand under the steeple

Drawing the cords that can draw the people,

And in our leash like the leaping dogs

Are God's most deafening demagogues:

And we are but little, like dwarfs underground,

While hang up in heaven the houses of sound,

Moving like mountains that faith sets free,

Yawning like caverns that roar with the sea,

As awfully loaded, as airily buoyed,

Armoured archangels that trample the void:

Wild as with dancing and weighty with dooms,

Heavy as their panoply, light as their plumes.

Neither preacher nor priest are we:

Each man mount to his own degree:

Only remember that just such a cord

Tosses in heaven the trumpet and sword;

Souls on their terraces, saints on their towers,

Rise up in arms at alarum like ours:

Glow like great watchfires that redden the skies

Titans whose wings are a glory of eyes,

Crowned constellations by twelves and by sevens,

Domed dominations more old than the heavens,

Virtues that thunder and thrones that endure

Sway like a bell to the prayers of the poor.

==

For Four Guilds completed. For now, let us revel in its majesty; tomorrow shall come the analysis.

The (Wo)Man Who Heard Thursday

Tolkien & Temptation

What separates Tolkien’s work from other narratives, especially those inspired by his prose, is the rich profundity and dexterity with which he wove his tapestry. Recent scholarship has shown the interconnectedness of Tolkien’s writing to the vaunted schools of ancient philosophy, specifically those of ancient Greece. However, there exists in The Lord of the Rings a subtle yet quite detectable call to the thought of the medieval philosopher St. Augustine. This call is particularly resonant today, an age where there appears to prevail an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. Augustine, as a student of the ancients (in particular of Plato), knew well that knowledge was not synonymous with wisdom. Often, the quest for the former entailed the preclusion of the latter.-- Dr. Jose Yulo, "The Temptation of the Earthly City: Tolkien's Augustinian Vision" at IgnatiusInsight.com; Feb 1, 2006

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

For Four Guilds III: Stone-Masons

III. The Stone-Masons

We have graven the mountain of God with hands,

As our hands were graven of God, they say,

Where the seraphs burn in the sun like brands

And the devils carry the rains away;

Making a thrift of the throats of hell,

Our gargoyles gather the roaring rain,

Whose yawn is more than a frozen yell

And their very vomiting not in vain.

Wilder than all that a tongue can utter,

Wiser than all that is told in words,

The wings of stone of the soaring gutter

Fly out and follow the flight of the birds;

The rush and rout of the angel wars

Stand out above the astounded street,

Where we flung our gutters against the stars

For a sign that the first and last shall meet.

We have graven the forest of heaven with hands,

Being great with a mirth too gross for pride,

In the stone that battered him Stephen stands

And Peter himself is petrified:

Such hands as have grubbed in the glebe for bread

Have bidden the blank rock blossom and thrive,

Such hands as have stricken a live man dead

Have struck, and stricken the dead alive.

Fold your hands before heaven in praying,

Lift up your hands into heaven and cry;

But look where our dizziest spires are saying

What the hands of a man did up in the sky:

Drenched before you have heard the thunder,

White before you have felt the snow;

For the giants lift up their hands to wonder

How high the hands of a man may go.

==

We will conclude tomorrow with the fourth part (the bell-ringers), and Friday will possibly see some small analysis of the poem.