link to the full interview

IgnatiusInsight.com: What are some of the common sense lessons we can learn today from G.K. Chesterton?

Ahlquist: Three things come to mind.

First, there is a reason to trust tradition, and be skeptical of new things. The modern world has that one exactly backwards: old is bad; new is good. Newer is even better. "A new philosophy," says Chesterton, "is generally the praise of some old vice." The irony arising from this is that it is now counter-cultural to defend morality and faith and the ancient truths that have been handed down to us by the Church.

Secondly, Chesterton's defense of the family as the center of life and the home as the most important place is a lesson badly needed today. All of our focus is on things outside the home: careers, politics, entertainment, sports. And none of these things are nearly as important as the caring for the souls of our children and the deepening of the sacramental relationship between husbands and wives.

Thirdly, poems should rhyme.

Monday, July 31, 2006

New D.Ahlquist Interview at I.Insight

Conflicted Round-up

Does Islam need a Reformation? Not unless you think it would benefit from additional dollops of Puritanism; further encouragement to smash altars, stained glass, and other forms of “idolatry”; prodding to ban riotous celebrations like Christmas and Easter; and support for fundamentalist Islamic schools that insist on sola Korana and sola Sunnah . Indeed, it would seem that Islam has already had its reformers.Ouch.

==

A colleague of mine has an extended look at the differences between man and woman. As well as being Catholic, she has a background in English and the family/educational sciences, so there is certainly much here for one to mull over. The linked post is just the introduction; she has produced several installments since. Give it a shot, people!

==

With the characteristic cool rationalism and objectivity of the truly dedicated scientist, a professor of psychology at the University of Washington has offered up a plea for the splicing together of human and chimpanzee DNA simply on the grounds that it would bother Christians. Prof. David P. Barash lays it out for us in one of the most elaborately fraudulent, belief-beggaring passages I have ever encountered:

In these dark days of know-nothing anti-evolutionism, with religious fundamentalists occupying the White House, controlling Congress and attempting to distort the teaching of science in our schools, a powerful dose of biological reality would be healthy indeed.Words can not express the eye rolling that should meet this statement.

==

There is evil in this world, but it's all okay so long as you can use it to take potshots at President Bush. The contents of this link may make your blood boil as it is, but if you are yourself a mother or (somehow) a young child, it could be held up as legitimate provocation for all manner of blood-soak'd acts.

==

The higher they ride, the more sweepingly and alarmingly they fall. As Abraham Lincoln once said, 'tis better to remain silent and be thought a mean drunk, and an anti-Semite to boot, than to open one's mouth and remove all doubt. It is of course my hope that the whole affair is either a misunderstanding (albeit an intensely explicit and unlikely one) or a case of slander, but somehow it doesn't seem like it's going to end so sunnily. For shame.

==

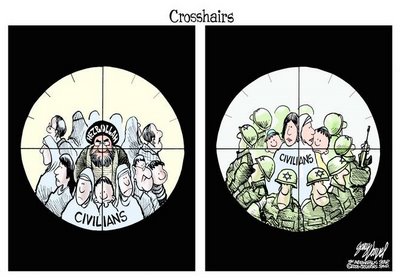

A potent dichotomy. Gilbert couldn't have put it better in prose:

This war will end, one way or another, and nobody involved is simply going to be going back to the way things were. That's about as hopeful a thing as can be said at this moment.

Friday, July 28, 2006

The Death of Ulysses

In any event, now that I have been freed from this waiting game, I can do what I like with this year's submission. I worried upon submitting it that it was not as upbeat as one might expect from a Chestertonian, or perhaps that it rambled intolerably. All of this could likely be true. However, reading it now, I don't know that I would change a word. I would likely add several, for the length limits of the contest were strict, but otherwise... yeah.

Here it is, then. I hope to hear what you think of it. I'll be posting it on my own blog, too, because I can.

==

The Death of Ulysses

The Death of UlyssesOne of the most urgent and vital lines in all of Dickens can be found in Great Expectations, and it runs something like this: “Think for a moment of the long chain of thorns or flowers that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day.” Such an exercise is not difficult, though it is rarely engaged. It is simply the act of tracing back a chain of influences as far as one can to see if there is some singular event upon which one might pin the responsibility for all that has followed. Without going into dreary specifics, I can tell you that I owe much of my current success to the idle purchase of a book about the battle of

Now, you may question the practical value of such an exercise, and I would, in many degrees, be right there with you in doing so. The point of it is not really to improve one’s life, but rather to see how easy it is for one’s life to change. To see the monumental happenings that can spring forth from the most seemingly insignificant of seeds. The point is to get you out into the garden.

It is for this broad reason that in reading Dickens’ words today there is almost the feel of tragedy. Though modern progress is often touted as having made everything so very much easier, it is doubtful that this is really such a good thing. One of the costs of not having to do many things is that not many things get done. Certainly, various tasks are accomplished. The children are taken to school, the report is filed at work, dinner is prepared, etc. But these are only accomplishments in a most literal and charitable sense. There is in them nothing of that exalted “first link” of which Dickens spoke. We have very much an easy existence, but almost nothing of a life.

Chesterton stood mightily against such weakening of the human character, body and spirit, and in doing so he finds himself alongside some unlikely allies. The scandalous novelist D.H. Lawrence declares in his essay, “Morality and the Novel,” that the weight of cynicism is destroying life in literature. “A thing isn’t life,” he says, “just because somebody does it.” We could take up this brazen sentence as a rallying cry and be none the worse for it. Even Nietzsche, for all his failings, would stand with us. Though there is in him much of what is wrong with man, it could never be said that he discouraged action. Though we must condemn the Dionysian, there is no finer dancer living.

Chesterton’s own position can best be derived from a parable. In “Homesick at Home,” we see the curious story of a man who literally travels round the world to get to where he already is, and experiences much along the way. “Like a transmigrating soul, he lived a series of existences: a knot of vagabonds... a crew of sailors... each counted him a final fact in their lives, the great spare man with eyes like two stars, the stars of ancient purpose.” This man is not only having seeds planted within him, but is himself a seed. Who can measure what joys he brought those vagabonds, or what tales are told of him by those sailors?

And we must not forget Chesterton’s distributist sympathies, for it is the scourge of wage slavery that is most singularly responsible for the deadened state of modern man. He labours at work that does not require thought, inspire the mind, or caress the soul. In his limited leisure time, he has neither the energy nor the will to dare great things or forge links. He atrophies. And does the world help him fight against this slow death? No, it does not. It provides him with a surrogate life to keep him from the real one he is missing. It provides him with reality television to distract him from reality. It provides him with Internet worlds to keep him from the real world outside his very door. It provides him with celebrities in place of heroes, fads for traditions, and buzzwords for truths.

And so we come, perhaps belatedly, to the title of this monograph. In Tennyson’s marvelous “Ulysses,” we see a perfect emblem of this striving against mediocrity. In the poem’s closing lines, there is an echo of Dr. Bull’s thundering sentiments about the character of the average man in The Man Who Was Thursday, to the effect that, jaded though he may be by cynicism and skepticism, he is still above the barbarism of anarchy. That he says this as an apparently anarchist mob pursues him is significant, as it sets the stage for our own reading of Tennyson’s glorious finale:

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in the old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal-temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

There was a time - and it was not long ago - when reading these words sent a golden thrill up my spine. Now, however, I can only look upon them and worry.

Disastrous Round-up

In any event, a few things worth considering, but not so many as usual; I have a substantial post with which to follow this up.

==

A California radio station has offered a profound theological service to the listening public by re-enacting the Fall of Man in miniature. It remains to be seen whether or not this mimicry will continue with some sort of blood-soaked redemption, but prospects at this time are not so good. I'd recommend that you stay tuned for further details, but there seems to be some sort of disinclination to do so, in this case.

==

Last year, Christians (Fundamentalist Protestant) engaged other Christians (Catholic, some Chaldean Catholic) in a street brawl in an effort to save their souls. Tensions mount this year as the anniversary approaches. There is a passage in a Graeme Greene book that I would like to cite.

One day, however, when Milly was thirteen, [Wormold] had been summoned to the convent school of the American Sisters of Clare in the white rich suburb of Vedado. There he learnt for the first time how the duenna left Milly under the religious plaque by the grilled gateway of the school. The complaint was of a serious nature: she had set fire to a small boy called Thomas Earl Parkman, junior. It was true, the Reverend Mother admitted, that Earl, as he was known in the school, had pulled Milly's hair first, but this she considered in no way justified Milly's action which might well have had serious results if another girl had not pushed Earl into a fountain. Milly's only defence of her conduct had been that Earl was a Protestant and if there was going to be a persecution Catholics could always beat Protestants at that game.==

No mere person could be this hideous. There must be some other quality to Hillary Clinton that accounts for the ominous, alienated feeling one gets when one looks upon this image.

Yes, in an startlingly premature move, the Museum of Sex in New York NY will be unveiling Hillary's Presidential Statue, jumping the gun by two years and likely an entire plane of reality. As is typical with such nonsense, the bust's unbearable ugliness is meant to challenge our perceptions of this and confront us with how threatened we feel by that. The conclusion, as ever, is that all revulsion is a matter of cringing and even unconscious fear, and that no settled perception can possibly be correct. This is what we get in a world without value judgments.

Anyway, my question is, what good is returning to the classical bust style if you're not going to be crafting a hagiographical sculpture? That's sort of the point of them. I suppose this could represent a legendary figure to some sort of person, but it sure as heck doesn't for me. My other question is with regard to how much of the taxpayer's money was siphoned through the NEA for the production of this otherworldly piece.

==

Finally, be sure to check out Alan's post about Islam just below; he likes to post just before the day is out, and we wouldn't want it to get lost in the new updates.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Round-up break

However, we've got stuff from Joe and Lee for you to read, so I'm sure you won't get bored. Look for the round-up to return tomorrow.

Hilaire Belloc, born 27 July 1870

Myself, Grizzlebeard, Sailor, and Poet

The moon on the one hand, the dawn on the other:

The moon is my sister, the dawn is my brother.

The moon on my left and the dawn on my right.

My brother, good morning: my sister, good night.

[Hilaire Belloc, "The Early Morning"]

Short stories (I)

I begin with the first three tales: "Half Hours in Hades," "The Wild Goose Chase," and "The Taming of the Nightmare."

All three tales are dated 1891-1892. That means that they were written when he was approximately 17 or 18 years old.

They read like a young writer's efforts. At times he seems more in love with the words or with being clever than with advancing the story. Still, there are glimpses of the humor and style that mark his later writings.

"Half Hours in Hades" is subtitled "An Elementary Handbook of Demonology." It includes illustrations.

This three-section piece reads like a partly completed work. Indeed, in the preface, the "author" says he was moved to write "this little work" after an "eminent Divine" suggested he write a book about demons.

The first two sections of the story describe the five primary types of demons, and the evolution of demons. There are references to Milton and Goethe and the types of demons they present in their works.

The most amusing section was the one on the "blue devil" which "have frequently been domesticated in rich and distinguished houses, and many of the wealthiest and most successful men of commerce may be seen with a string of these blue creatures led by a leash in the street or seated round him in ring on his own fireside."

Yes men?

Chesterton suggest that the blue devil, with the "singularly melancholy and depressing" noise that it makes, and less than "lively" general appearance, might be "a suitable pet for the houses of clergymen and other respectable person."

But then the piece suddenly shifts in section III to a the story of a witch telling her children about demonology, and doing some conjuring in a cauldron. Among the ingredients tossed into the cauldron is "the liver of a blaspheming Jew" – one of the kinds of statements that later led people to accuse Chesterton of being anti-Semitic (a charge I think was false, by the way.)

On the whole, I think this "story" is an experiment that deserved not to be finished.

The next tale is an entirely different matter.

"The Wild Goose Chase" is, I think, a successful tale. The title is a pun, of course. The "Little Boy" in the tale is indeed chasing a wild goose, but it also refers to all the wild goose chases we sometimes engage in.

Along the way he meets a vain Bird of Paradise, a nightingale - a musician who has lost his work - and a owl that is waiting for all the leaves to fall from the Tree of Knowledge, a "doosid original" vulture, and more. All the creatures are vaguely recognizable as human types.

He loses the goose, but by acting to save a bird from an eagle, he gets back on the trail. When he loses it again, it is by rejecting the opportunity to go back and forget everything he has experienced on his quest that he is able to rediscover the trail again, and continues on.

The story is a metaphor for all the quests/goals that challenge us. Fame? Fortune? Art? Faith? Some folks consider them "wild goose chases," but for the person, they give life purpose.

Not a great tale, but successful. I see shadows of future better quest tales in it – such as The Man Who Was Thursday.

The third tale of this trio is "The Taming of the Nightmare." Another word play in the title. Another quest tale – more of a fairy tale in the Grimm mold - but I think it’s not quite as good the "Goose" story.

In this case, it is the story of Little Jack Horner (yes, of nursery rhyme fame) who is sent to capture and tame the "Nightmare." I won’t spoil the end other than to say he does meet up with the Nightmare (and the title gives away what happens!), but he does meet some interesting characters along the way (a Gardener, turnip ghosts, a king, etc.).

The best of these characters is the Mooncalf, a mournful poetic creature.

I forget all the creatures that taunt and despise,

When through the dark night-mists my mother doth rise,

She is tender and kind and she shines the night long

On her lunatic child as he sings her his song.

The Mooncalf alone makes this tale worth reading!

On the whole, these three tales give us a taste of what is to come – satire, fanciful characters, quests, word plays, a bit of poetry, and so on.

And now, like the "Little Boy," I continue my wild goose chase to read all the tales in this collection.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Marketing 101 with Professor Chesterton

The central character in a G.K. Chesterton novel finds it so important to maintain a solid and vibrant relationship with his wife that he continuously re-enacts their courtship.link to full article by by Nilofer Merchant

Do your customers look at your products with the same eager anticipation as they once did? Have your customers stayed "married" to you? Would you consider them still in love—or waiting it out until someone better comes along?

Kafkaesque Round-up

Today's round-up is dedicated to the legendary Czech/Jewish writer Franz Kafka, who lived a hard life in many ways and died terribly for his troubles. There is much in Kafka for our readers to admire, if they are not already doing so, and you may begin your admiration with the goodly selection provided here. Those of you able to read German will do well to note that the website's main function is to make Kafka's works available to the public in their original German manuscripts. Those wishing to hear what novelist Vladimir Nabokov (Lolita; Bend Sinister) has to say about Kafka can go here; those wishing to read a selection of Kafka's journals can go here. This latter project is particularly fun, as it contains delightful prose images like this:

Today's round-up is dedicated to the legendary Czech/Jewish writer Franz Kafka, who lived a hard life in many ways and died terribly for his troubles. There is much in Kafka for our readers to admire, if they are not already doing so, and you may begin your admiration with the goodly selection provided here. Those of you able to read German will do well to note that the website's main function is to make Kafka's works available to the public in their original German manuscripts. Those wishing to hear what novelist Vladimir Nabokov (Lolita; Bend Sinister) has to say about Kafka can go here; those wishing to read a selection of Kafka's journals can go here. This latter project is particularly fun, as it contains delightful prose images like this:"Beside me on the return trip from Raspenau to Friedland this stiff deathly man, whose beard hung down over his open mouth and who, when I asked him about a station, made a friendly turn toward me and gave me the liveliest information."It certainly seems the sort of thing that Gilbert would notice, and of course mention. Kafka himself was not silent on the subject of Gilbert, in fact, saying, "he is so happy! I can almost believe that he has found God." Amen, Franz.

Lastly, a truly excellent Prague monument to Kafka can be seen here.

==

We have good and bewildering news out of Ireland, where a construction worker digging up an old bog happened to discover by pure and astonishing chance a well-preserved medieval book containing copies of some of the Psalms. The book has been dated as being 800 to 1000 years old, and is of incalculable value to any field that might conceivably have an interest in it. How it survived in the swamp for all this time is a mystery, as is what it was doing there in the first place. And, of course, the manner of its discovery is certainly fortuitous; the slighest extra effort on the workman's part in either direction could have either left the book hidden or destroyed it utterly.

The thing that really grabbed me about this story is that the book was open when it was found, and, what's more, it was open to the highly topical and relevant Psalm 83. The text of that Psalm follows, in part:

1 Keep not thou silence, O God: hold not thy peace, and be not still, O God.

2 For, lo, thine enemies make a tumult: and they that hate thee have lifted up the head.

3 They have taken crafty counsel against thy people, and consulted against thy hidden ones.

4 They have said, Come, and let us cut them off from being a nation; that the name of Israel may be no more in remembrance.

5 For they have consulted together with one consent: they are confederate against thee...

[. . .]

13 O my God, make them like a wheel; as the stubble before the wind.

14 As the fire burneth a wood, and as the flame setteth the mountains on fire;

15 So persecute them with thy tempest, and make them afraid with thy storm.

16 Fill their faces with shame; that they may seek thy name, O LORD.

17 Let them be confounded and troubled for ever; yea, let them be put to shame, and perish:

18 That men may know that thou, whose name alone is JEHOVAH, art the most high over all the earth.

==

Witness - if you dare! - two examples of a Catholic blogger reverting to Fundamentalist Protestantism (or... something) when the going gets tough. An improperly-shaded banner in a local Church is a sure sign of its apostasy! A traditionalist website is deceitfully ascribing gnostic-sounding quotes to John Paul Magnus! Gilbert editor Sean P. Dailey had this to say:

One of the benefits of belonging to a religion with unbending dogmas is that with those dogmas comes a surety that allows you to laugh at yourself, even if the butt of the jokes is a beloved Pope, and I bet that JPII also would find the site funny and would be perplexed by Tomko's umbrage, the source of which is nothing but damnable pride. "Angels fly because they can take themselves lightly," Chesterton wrote, while "Satan fell by the weight of his own gravity."There's been something of a meltdown in Mark Shea's comboxes about this issue, too. People are so intense and weird, often at the same time.

==

The triolet contest at Enchiridion has come to an end, and it is now time to vote. Please feel free to head over there and vote for whichever submission you feel is worthwhile. If it's one that was authored by someone's whose words you're reading right now, so much the better.

==

Those of you wishing for a light-hearted excursion would do well to read this brief narrative (my own, as it happens) of what happens when a single agent of the medieval past comes into contact with the full force of the modern aesthetic. The answer: a riot; an understanding; a brush with celebrity (Hilary Duff!). I have struggled with whether or not the whole affair really qualifies as being "Kafkaesque" or not - indeed, I thought of it on the way home, to shake myself out of the experience, if anything - and I am still not certain that it does. It's extraordinary, certainly, but hardly mundane. As there are few things that bother one so as when someone applies the phrase "Kafkaesque" to some circumstance to which it really does not apply, my concern about this is perhaps worthwhile.

Those of you wishing for a light-hearted excursion would do well to read this brief narrative (my own, as it happens) of what happens when a single agent of the medieval past comes into contact with the full force of the modern aesthetic. The answer: a riot; an understanding; a brush with celebrity (Hilary Duff!). I have struggled with whether or not the whole affair really qualifies as being "Kafkaesque" or not - indeed, I thought of it on the way home, to shake myself out of the experience, if anything - and I am still not certain that it does. It's extraordinary, certainly, but hardly mundane. As there are few things that bother one so as when someone applies the phrase "Kafkaesque" to some circumstance to which it really does not apply, my concern about this is perhaps worthwhile.Speaking of misassigning Kafka, when I said at the beginning that this round-up was dedicated to him, I didn't mean that it was all going to be about him, but rather that it's just being done in his name as a sign of respect, or something. I should perhaps have made been more clear about this, for it's possible that many of you who have now read this far feel somewhat betrayed.

In any event, these round-ups have been something of an experiment to see how best to bring more varied content to the blog. I could easily split them up into individual posts for each topic, if this were a more favourable idea, but I must confess that I really have no conception of how popular the round-up format is in the first place, or whether the variety of its content is too varied, not varied enough, etc. I encourage you to comment on this below, if you would be so kind.

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

Blasphemers and God

"An American who began her career as a journalist in Belfast, claims she is a descendant of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene and is publishing a book about it.

"Kathleen McGowan has received a seven-figure advance for her novel, "The Expected One," said the Sunday Times of London."

Link.

Bedtime Round-up

==

Mark Shea goes berserk, but in a good way that we can all totally dig. There's fisking and exasperation and measured restraint galore, here, and it's worth every line. The experience reminds me of a line from Maisie Ward's Gilbert biography, wherein are described some of the skeptical/socialist/etc. pamphlets and books that were left, in crumpled and note-splattered condition, lying hither and yon about the Chesterton manse. To paraphrase: "They had a refuted look to them."

==

"I don't think the government should listen to the church - the government should listen to the people and the people should listen to the church."Which Archbishop said this? What brought it about? Was the response a scandalised gasp, or a rugged cheer? Well, there's only one way to find out, and that's by clicking this here link. Warning: link contains candor!

==

The modern grasping for the realities of the divine through ersatz mythologies continues unabated, and some familiar symbols and heroes are on their way back. There are many of a certain generation for whom the sight of this image will produce a little frisson of glee, curious and tacky though the mythology of the thing may be:

And of course, to join the ranks of The Gift of God, the Coming of Age and the Triumph of the Will comes The Lush in the Robotic Suit:

And of course, to join the ranks of The Gift of God, the Coming of Age and the Triumph of the Will comes The Lush in the Robotic Suit:

Be sure to click on each image for nicer, larger versions. If you're a fan of the dastardly Decepticons rather than the admirable Autobots, however, then the poster you'll want to see is here.

==

Those of you who stand rapt and shivering in the dark grace that Flannery O'Connor championed (as mentioned in a recent round-up) may wish to witness the latest photographic efforts of Gerald at Closed Cafeteria, which are considerable efforts indeed. To see the Holy Spirit Descending so triumphantly in blood, fire and shadow is truly thrilling, and is not something that we frequently get from a man taking a picture at his local beach.

==

To close out the links on a dolorous note, as we have been known to do, it is worth mentioning that fellow Chestertonian blogger Rod Bennett has suffered the loss of a friend of long standing, and is requesting prayers for his family and for the repose of his soul.

==

And finally, of course, don't forget the latest from Alan Capasso, which was technically posted yesterday, by EST standards, but is nonetheless as fresh and new as that moisture that collects on stuff outside in the morning hours sometimes.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Brief Round-up

In breaking and utterly shocking news, a "progressive Catholic" has been given an inch, and, not satisfied even with the foot that would typically follow, is now stolidly working her way up the entire leg. The new Theology Chair of the University of Loyola went on record with some profoundly stultifying remarks, flying in the face of nature, the Church, and common sense. Not even condescending to admit that she is herself a fringe-inhabiting oddity, she went on to affirm her belief that the Church will eventually fall into line with her own way of thinking.

And, actually, that's all I have time for. I'll mention briefly that there's a rumour from the official ACS blog that an annotated edition of The Everlasting Man is in the works. Be sure to head on over there for the discussion.

Friday, July 21, 2006

Public TV That Got Me Thinking

A couple days ago, I watched a special on Public TV dealing with communication of ideas through images. Although that sounds rather drab, the program featured cultures throughout history and examined their ways of communicating ideas and passing on traditions. There were examinations of Greek Tragedy, Roman bas-reliefs, but what struck me the most was the segment on the Aborigines of Australia.

The Aborigines most likely have the oldest continuing culture of any group in the world today. As the documentary unfolded, the audience was shown cave paintings dating back thousands of years. Amazingly, these cave pictures are nearly identical to the forms found in contemporary Aboriginal art. Much like Byzantine Icons, the pictures are not a series of narrative illustrations, but rather each individual drawing contains layers of meanings derived from its form, decoration, and position. In order to grasp the full meaning of the drawings, one needs to have an elder interpret it and tell the entire story.

There was another aspect to this entire scene, which should raise some interesting points. The pictures and the stories were incomplete outside of a story-telling ritual. The old and young Aboriginals would gather at night around the paintings, and amidst drums, the stories and myths were told through chant.

To me, the liturgical overtones in this scene were powerful. So many basic truths easily forgotten -- The powerful roles played by art, beauty, and sacred space are wound into our beings in a very fundamental way. The Aboriginals have an unbroken lineage going back to the dawn of language itself, yet (this had to be coming) within the Catholic Church we have suffered a forty year cataclysm in catechetics, liturgy, and passing on the Faith itself.

This whole scene reminded me of some bits and pieces of Chesterton. The themes and images of The Everlasting Man are evoked from this primitive scene. As a matter of fact, I distinctly remember GKC mentioning the Aboriginal myth of the great flood. A giant frog had swallowed the waters, and refused to spit them out. All of the animals went to ask the frog to relent and failed until the eel arrived. The eel was comical, tumbling and spinning around out of water, and the frog laughed and spewed forth the waters, causing the flood. If I remember correctly, the Aboriginals are also monotheistic.

Our culture has designed focus groups, multimedia presentations, tutors, standardized testing, no child left behind, and graduate studies departments bursting at the seams to devise new and better ways to teach children. The fact that the most proven and long lasting means of teaching can be observed as being........liturgy........should be a sobering thought.

A clerihew

crossed deserts and the sea, see,

to convert the sultan.

He failed, but did inspire Chesterton.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Scrutinous Round-up

Belle sings it: "Every day/Like the one before." The same thing can happen in a castle. Routine is a part of life. Family is a part of life. Someone like Chesterton would even argue that they are good parts of life, that ordinary life, even in the midst of its routine, is fraught with romance and drama, and not to be fled.

"You want to be rid of me?" asked Zuleika, when the girl was gone.What promise? Who is the gentleman who's speaking? All this and more if you simply read the book. Anyhow, that's all I have time for right now, for I am on vacation. Have a good weekend.

"I have no wish to be rude; but -- since you force me to say it -- yes."

"Then take me," she cried, throwing back her arms, "and throw me out of the window."

He smiled coldly.

"You think I don't mean it? You think I would struggle? Try me." She let herself droop side-ways, in an attitude limp and portable. "Try me," she repeated.

"All this is very well conceived, no doubt," said he, "and well executed. But it happens to be otiose."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean you may set your mind at rest. I am not going to back out of my promise."

Clerihew

Sir Humphrey Davy

Abominated gravy.

He lived in the odium

Of having discovered sodium.

This simple silly verse is commonly considered the first clerihew, a poetic form named for its creator, Edmund Clerihew Bentley. He was a school friend of GKC, who also wrote some clerihews, and provided illustrations for some of Bentley’s (like the one above.) Bentley allegedly came up with the idea for the biographical poems while bored at school. Whatever the case, he later published a book of them (Biography for Beginners) with illustrations by Chesterton.

The form of the poem is simple:

They are four lines long.

The first and second lines rhyme with each other, and the third and fourth lines rhyme with each other.

The first line names a person, and the second line ends with something that rhymes with the name of the person. (In some cases, the person’s name comes at the end of the second line, in which case the first line rhymes with the name.)

The lines can vary in length, they just have to rhyme.

A clerihew should be funny.

That’s about it.

Oh, and of course, even Bentley broke the person rule occasionally. Here’s an example (with another Chesterton illustration.)

The art of Biography

Is different from Geography.

Geography is about maps,

But Biography is about chaps.

The clerihew is beloved by Chestertonians. There is a regular column about them in Gilbert magazine, and the annual Chesterton Conference includes a clerihew contest.

As noted earlier, Chesterton’s connection with clerihew’s goes beyond simply illustrating them for Bentely: He wrote some himself.

Three that are attributed to GKC are:

The novels of Jane Austen

Are the ones to get lost in.

I wonder if Labby

Has read Northanger Abbey

(Labby was an English journalist.)

Whenever William Cobbett

Saw a hen-roost, he would rob it.

He posed as a British Farmer,

But knew nothing about Karma.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Is now a buried one.

He was not a Goth, much less a Vandal,

As he proved by writing The School for Scandal.

Bentley is the most famous of the clerihew writers. W.H Auden also published a book of them (Academic Graffiti).

Henry Adams

Was mortally afraid of Madams:

In a disorderly house

He sat quiet as a mouse.

Oscar Wilde

Was greatly beguiled,

When into the Café Royal walked Bosie

Wearing a tea-cosy.

More recently, Pulitzer Prize winning poet Henry Taylor published a collection of Clerihews called Brief Candles, 101 Clerihews. Here’s two of his:

Thomas Warton

never met Dolly Parton.

It made him quite surly

to have been born too early

Alexander Graham Bell

has shuffled off this mobile cell.

He’s not talking any more

But he has a lot to answer for.

But getting back to the Bentley, here’s a few more:

Sir Christopher Wren

Said, 'I am going to dine with some men.

If anyone calls

Say I am designing St. Paul's.'

John Stuart Mill,

By a mighty effort of will,

Overcame his natural bonhomie

And wrote 'Principles of Economy.'

Edward the Confessor

Slept under the dresser.

When that began to pall,

He slept in the hall.

Chapman & Hall

Swore not at all.

Mr Chapman's yea was yea,

And Mr Hall's nay was nay.

There’s even a Mystery Clerihew site - http://www.smart.net/~tak/clerihew.html - (appropriate, because Bentley’s greatest fame came from his mystery book, Trent’s Last Case) where I came across the following:

Father Brown

Gained wide renown.

Not for prayerbooks or hyminals,

But for collaring criminals.

And here’s a final Bentley, with a GKC illustration:

What I like about Clive

Is that he is no longer alive.

There is a great deal to be said

For being dead.

Succulent Round-up

In other Ignatius news, Insight Scoop is also reporting that Pope Benedict XVI is hard at work on a new book about the theology of the person of Christ - a book which he initially left off writing upon his elevation to the station of Pope - as well as a new encyclical. This latter work will be of great interest to fans of Chesterton and Belloc, for it is slated to be broadly concerned with human labour. Could we be seeing an encyclical to join the exalted ranks of the likes of Rerum Novarum and Laborem Exercens? If it's of similar quality to Deus Caritas Est, I think we'll all have reason to be glad.

Proving in a novel way that they are the pricks against which the devil must kick, the House voted 349-74 yesterday to preserve the Mt. Soledad war memorial by transferring the title deed thereto to the Federal Government, and thereafter having the site be administered by the Department of Defense. The enormous off-white cross has been the subject of almost twenty years of legal challenges on behalf of one little atheist and his frustrated cronies, who were last seen weeping like heartbroken schoolgirls over a meal of tapwater and Plain Leavened Wafers.

And finally we'll close with something that's a bit of a tradition for me, as far as space-fillers go: a Gustave Doré plate. Be sure to click on it for a version of the same image enlarged almost the point of vulgarity.

The image is a plate from Gustave Doré's illustrated edition of Ariosto's Orlando Furioso. Part of the appeal that Doré has always had for me is his ability to render things in a technically realistic manner, and yet still manage to create an air of almost mystical wonder to virtually anything he depicts. When I think to myself of the concept of a procession of the Knights of Europe passing some eastern potentate, the image above is almost exactly how I would imagine it, and almost exactly how I feel Chesterton, for example, might have described it. In any event, if you've never seen any Doré before, you have many happy hours ahead of you. If you have, however, then you are already blessed.

The image is a plate from Gustave Doré's illustrated edition of Ariosto's Orlando Furioso. Part of the appeal that Doré has always had for me is his ability to render things in a technically realistic manner, and yet still manage to create an air of almost mystical wonder to virtually anything he depicts. When I think to myself of the concept of a procession of the Knights of Europe passing some eastern potentate, the image above is almost exactly how I would imagine it, and almost exactly how I feel Chesterton, for example, might have described it. In any event, if you've never seen any Doré before, you have many happy hours ahead of you. If you have, however, then you are already blessed.Wednesday, July 19, 2006

GKC Pun

Probably the worst pun in the history of the English language was penned in July of 1944 by the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas when he wrote, "We were two months near

Infamous Round-up

And he says this, that when Christ went up into the heavens, God questioned him, saying, “O Jesus, did you say that ‘I am the Son of God and God’?” And Jesus, they say, answered, “Have mercy on me, O Lord; you know that I did not say (that), nor am I too proud to be your servant, but men who have turned aside wrote that I said this word and lied about me, and are wandering.” And God, they say, answered him, “I know that you did not say this word.”And many other astonishing sayings in this same writing, worthy of laughter, he boasts God sent down to him.There is no sugar-coating here, I say to you. This was an age before sugar. Many skeptics and anti-clericals look back at the Early Fathers as "jerks," I suppose we could say, for the heinous crime of daring to dismiss heresy as the foolishness that it is. Irenaeus is moved to open and mocking satire at one point in his dealings with the claims of the old heresiarchs; who could expect less from John of Damascus?

To follow up on Monday's link to the myth of religious tolerance we bring you the very last word in brazen, name-taking majesty, courtesy of the marvelous Dorothy Sayers:

To follow up on Monday's link to the myth of religious tolerance we bring you the very last word in brazen, name-taking majesty, courtesy of the marvelous Dorothy Sayers:"In the world it is called Tolerance, but in hell it is called Despair, the sin that believes in nothing, cares for nothing, seeks to know nothing, interferes with nothing, enjoys nothing, hates nothing, finds purpose in nothing, lives for nothing, and remains alive because there is nothing for which it will die."We offer a hat-tip to Kathy Shaidle for that one. What's more, if your tolerance for tolerance is still rather high, feast your eyes upon this monstrous dialogue in the old high style, in which Silvius goes to bat for the Big T, and is consequently eviscerated by the noble Memnon. As always, of course, it is heavily informed by Gilbert.

We must stop worrying about whether or not our actions hurt other people, and start worrying about whether or not those actions help other people. To predicate one's life on merely avoiding harm to others is not as selfish as one could be, but is selfish nonetheless. It is no longer sufficient for real men to concentrate on merely not taking; they must now turn to actually giving.And finally, we hope you will join Nancy Brown at the American Chesterton Society's Blog in offering prayers for young Lucy - the daughter of a member of the Gilbert staff - who has fallen seriously ill. Holy Innocents, pray for her.

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Notable Round-up

From the strivings of a traditional Catholic comes a breathtaking clearinghouse of prayers for you and your family, in both English and Latin, with indulgence-related notation and instructions for posture after the Dominican fashion. It's an inspiring sight/site for adults, and for younger folks like me it stands invitingly as the pleasant means to a most noble end. A man ain't a man unless he can bellow in Latin, and poorly-worded imprecations about underwear simply don't cut it anymore.

"St. George forever!" they cried as they marched off to their deaths. "Yeah, about that..." said certain Anglicans. Not to disrespect St. Alban, who was a righteous gentleman to be sure, but he didn't slay any dragons. I've heard it said by some that St. George should be made the honourary president of the St. Christopher Society for Fanciful Saints, but such complaints lack merit. What these fellows actually mean by that is that we should just ignore him as fiction. The idea that mankind is likely to ignore fiction, or even that it should, is far more fanciful and absurd than any number of extravagant, monster-slaying supermen, however, and should be dismissed as the foolishness that it is.

Whatever their mounting theological and moral problems, it's good to see that the Episcopalians can still maintain an impressive-looking Cathedral (sometimes), and even have a sense of fun about things. You're either going to love or hate this one, ladies and gentlemen; there is no middle ground. You've been warned. In any event, you can find more information about this astonishing feature here, and more about the Cathedral in general here.

Should we take it as a compliment that, as Bishop Fulton Sheen once remarked, more people attack of an elaborately-constructed caricature of the Church than actually dare to attack the Church Herself? If so, young Charlotte Church has paid our Mater Ecclesia the greatest compliment ever rendered by human effort. Huh... Church vs. Church. The secularists will be bemoaning this latest holy war, no doubt.

Monday, July 17, 2006

The Autistic GKC?

"For most people, religion is an emotional thing. For me, it is primarily intellectual, although there is emotion there as well. Life is a magical thing. The explanation of religion is crazy in a sense, but life is no less crazy. The mystery of it is just as weird and wonderful as religion's explanation of it. When scientists try to break everything down there's always a piece missing."(link to Jul 16 article by Catherine Deveny)

Esoteric Round-up

Flannery's favorite target tends to be nice, mild, middle class ladies, full of decent and righteous advice. Nice ladies. Elsie Dinsmore all grown up. Yet these women lie about grace all day long. They lie about Christ as they go about trying to make a utopia of niceness. Grace is much more surprising than their Victorian sensibilities could ever imagine.Some cringe at O'Connor's disposal of these ladies. Flannery famously gets a reader to side with a decent but perhaps slightly flawed lady, and then the story slowly turns grim. We see her smile is grounded in pettiness or deep bitterness. Finally, she has a severe encounter with dark grace. Nice readers close the story quickly and refuse to go on to another. It's as if the reader herself has been roughed up unjustly. But that's the point. Flannery just reflects Christ's priorities. He was much softer on thieves, prostitutes, and murderers than he was on polite, middle class Pharisees. Christ berates and belittles and promises death-from-heaven for the most decent citizens of Jerusalem. The good, law-abiding Rotarian sorts incense Christ's deepest anger. And, in Flannery's stories, grace hunts them down. All evil is not bad. Some evil comes to shake us out of our sin; some evil comes to liberate us. Some evil is a gift of grace. Grace gnashes.

The English translation of the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church is now online to be devoured with fervor. It is presented in a simple question-and-answer format, and is certainly profitable for all. Go check it out.

The mysteries of infamous sleuth Nancy Drew and authoress Agatha Christie distilled into computer programs. Now you can save the day, or at least the next few hours. Warning: link contains shameful revelations from a respected Gilbert columnist!

Pope Benedict XVI kicks back on his vacation and does something that somehow I never thought I'd see a Pope doing, delightful though it is.

The Rev. Thomas D. Williams, L.C., writes about the "myth of religious tolerance."

Religion is a good to be embraced and defended—not an evil to be put up with. No one speaks of tolerating chocolate pudding or a spring walk in the park. By speaking of religious “tolerance,” we make religion an unfortunate fact to be borne—like noisy neighbors and crowded buses—not a blessing to be celebrated.=

And finally, in tremendously sad news, noted Catholic authoress Regina Doman (The Shadow of the Bear) has suffered a terrible loss in the death of her young son, Joshua Michael. The eulogy for the young prince can be found here. Mother Mary, pray for them.

Friday, July 14, 2006

Barrett and Belloc

I know a little about Pink Floyd, and greatly enjoyed their music during the late 70s thru the 80s. Even in 1995 I had a relapse and went to see them perform at Texas Stadium; but that was long after Barrett was given the boot; it was even after Roger Waters ebbed into a solo career.

Syd Barrett loved Hilaire Belloc's Cautionary Tales. Yes, "Syd Who Founded Pink Floyd, Loved Barbiturates, Developed Schizophrenia, and Lived 30 Years as a Recluse."

"Matilda Mother," from The Pink Floyd's 1967 album Piper at the Gates of Dawn, was a reference to Hilaire Belloc's cautionary tale "Matilda Who told Lies and was Burned to Death." He originally wrote the song to include the story of "Jim Who Ran Away From His Nurse and was Eaten by a Lion," and during the early Floyd concerts it was sung that way:

There was a boy whose name was Jim.

His friends were very good to him.

They gave him tea, and cakes, and jam,

and slices of delicious ham.

Oh Mother, tell me more...

But the lyrics on the album are his own:

"Matilda Mother"

There was a king who ruled the land.

His majesty was in command.

With silver eyes, the scarlet eagle

showered silver on the people,

Oh Mother, tell me more...

Why'd you have to leave me there

hanging in my infant air, waiting?

You only have to read the lines of

scribbly black and everything shines.

Across the stream with wooden shoes,

bells to tell the King the news.

A thousand misty riders

climb up higher once upon a time.

Wondering and dreaming.

The words have different meanings...

Yes they did...

For all the time spent in that room,

the doll's house, darkness, old perfume,

and fairy stories held me high

on clouds of sunlight floating by.

Oh Mother, tell me more...

Thursday, July 13, 2006

Thomas Merton on Chesterton

He also wrote about Chesterton – but in a way Chestertonians might not like.

In a January 2, 1959, diary entry, he compares Chesterton with Swiss theologian, Msgr. Romano Guardini:

A very fine interview with Guardini was read in the refectory – a wonderful relief from the complacent windiness of Chesterton (St. Thomas Aquinas).

Ouch.

Guardini spoke of power poisoning man today. We have such fabulous techniques that their greatness have outstripped our ability to manage them. This is the great problem. “Difference between Guardini and Chesterton – Guardini sees an enormous, tragic crisis and offers no solution. Chesterton evokes problems that stand to become, for him, a matter of words. And he always has a glib solution. With Chesterton everything is “of course” “ quite obviously etc. etc. And everything turns out to be “just plain common sense after all.” And people have the stomach to listen and to like it! How can we be so mad? Of course, Chesterton is badly dated: his voice comes out of the fog between the last two wars. But to think there are still people – Catholics – who can talk like that and imagine they know the answers.

Yikes!

Of course, I disagree. I like Merton – I have even more of his books than I do of Chesterton – but I think he is unfair to Chesterton.

That view is echoed in Michael Higgens in his Heretic Blood: The Spiritual Geography of Thomas Merton.

Higgens speculates that Merton had fallen for the caricature of Chesterton that had been created by GKC's fans (and, to be honest, by Chesterton himself). What Merton was troubled by in 1959 was more the kind of "complacency represented by Chesterton and his kind." Chesterton had become for Merton a symbol of the old Catholicism.

Remember, this is while the winds of change were whirling just before Vatican II.

I wonder if Merton's view would have softened had he not died in 1968 at age 51. Would he have been more open to recognizing what Chesterton was about in the wake of Vatican II?

Chesterton certainly has come back into vogue, and in the cyclical way of the world, his words are relevant in a way that perhaps Merton could not appreciate in 1959 before Vatican II.

A bit of cheese

Of course, I believe he was writing with tongue in cheek (likely savoring a bit of cheddar).

A number of poets have written about cheese, including Chesterton himself ("Sonnet to a Stilton Cheese").

There’s even a Poet Laureate of Cheese: James McIntyre of Ingersoll, Ontario, Canada.

A Scotsman (hooray) who moved to Canada, McIntyre died in 1906 after composing a number of verses about his adopted home, including its cheese making.

Alas, as well as being referred to as "The Cheese Poet" and "The Chaucer of Cheese," he is also sometimes called "Canada’s Worst Poet." (No accounting for taste).

I recently stumbled across another bit of cheese poetics.

CHEE$E

By Joyce Killer-Diller

I think that we should never freeze

Such lively assets as our cheese:

The sucker’s hungry mouth is pressed

Against the cheese’s caraway breast

A cheese, whose scent like sweet perfume

Pervades the house through every room.

A cheese that may at Christmas wear

A suit of cellophane underwear,

Upon whose bosom is a label,

Whose habitat: - The Tower of Babel.

Poems are nought but warmed-up breeze,

Dollars are made by Trappist Cheese.

"Joyce" was actually Thomas Merton, commenting humorously on one of his monastery's major sources of income. (One suspects that Merton himself has posthumously helped the Abbey’s coffers!)

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Chesterteens

Still a Friend

Evelyn Waugh liked to send out satirical Christmas cards, and the apex (or nadir] of this practice was reached during the Christmas season of 1929. Waugh's card that year consisted of extracts reprinted from unfavorable reviews of his first novel, Decline and Fall. The harshest passage of all was taken from a review by Chesterton. [Christopher Sykes, Evelyn Waugh,

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

St. Benedict

We must remember that even to talk of the corruption of the monasteries is a compliment to the monasteries. For we do not talk of the corruptionof the corrupt. Nobody pretends that the mediaeval institutions began in mere greed and pride. But the modern institutions did.Nobody says that St. Benedict drew up his rule of labour in order to make his monks lazy; but only that they became lazy.Nobody says that the first Franciscans practised poverty to obtain wealth; but only that later fraternities did obtain wealth.

The Thing

[I]t is true to say that what St. Benedict had stored St. Francis scattered; but in the world of spiritual things what had been stored intothe barns like grain was scattered over the world as seed. The servants of God who had been a besieged garrison becamea marching army; the ways of the world were filled as with thunder with the trampling of their feet and far ahead of that ever swellinghost went a man singing; as simply he had sung that morning in the winter woods, where he walked alone.

St. Francis

Aside: I posted a fair amount about St. Benedict over at The Daily Eudemon.

Monday, July 10, 2006

Busy day

Mike Aquilina's The Way of the Fathers - A pleasant and wonderfully informative blog concerning the Early Church Fathers. This is one you should be reading if you aren't already.

Totus Pius - A fun and scandalous group blog, as conducted by a number of Popes (and one Antipope) named Pius.

The New Advent Blog - Finally back on track and being updated regularly, the blog of the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia is certainly worth your time, as is the Encyclopedia itself.

And of course, the almost-complete works of Chesterton online. There are still a few books and a few thousand essays to account for, but the rest of his body of work is, gratefully, available.

That should tide you over for a while, and again, apologies for the unattentiveness today.

Friday, July 07, 2006

Eugenics, among some other evils......

Bill Gates is stepping down from Microsoft to devote himself to his charitable foundation. Shortly after that, Warren Buffet, the second richest man in the world, put in motion an operation that will move appx. $37 billion to the already well established Gates Foundation.

In many ways, this could be seen as a good thing. Men of tremendous wealth, energy, and entrepreneurial insight have dedicated their resources to "make a difference" in the world. There is no precedent for this in the (notorious)history of finance, philanthropy, and business.

The Gates Foundation has done some good work in the areas of poverty and disaster relief. However, there is another aspect to this groups activities which we must object to. Population control, and abortion rights/access have also been recipients of the Gates' charity. Warren Buffet was also a key individual in funding the development of RU486.

To fully grasp the consequences of this action, let us put this in other terms. The two richest men in the world have pooled their resources, in good faith, to promote a plan of eugenics. Im certain that NGOs who work in population control efforts will be the recipients of most of these funds. I wonder what Chesterton would think of this conglomeration of big government and big business? Few seem to think much of it at all.

The end result is that no matter how eloquent the reasoning of the pro life position,(Why even call it a position?) irregardless of the legal gymnastics needed to keep the culture of death afloat, no matter how easily it can be shown how contraception and abortion destroy societies and individuals, the pro abort, culture of death side now has more funding and resources than could possibly be mustered against it.

I predict a couple things out of this. I think somehow the South Dakota abortion ban is going to be fought with funds ultimately traced back to this source. I also predict some very shallow, condescending reporting that is going to compare the good work of Bill Gates with that of Mother Teresa, and drawing a moral equivalency between them.

At least it is still free to think.

Thursday, July 06, 2006

More from Dawn Eden

Back in December 1995, as I was doing a phone interview with Ben Eshbach, leader of the rock band Sugarplastic. I asked him what he was reading those days. His answer was Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday.Be sure to read the whole thing, for it is surely worth it.

The name G.K. Chesterton meant nothing to me. I assumed he was an author of quaint comedic British novels, like P.G. Wodehouse.

I bought The Man Who Was Thursday out of curiosity and was fascinated. Being a fan of Lewis Carroll from childhood, I was instantly sucked in by Chesterton's surreal plot twists, especially with the playful ways he would switch around the heroes and villains.

[. . .]

Reading Chesterton, it struck me for the first time that there was something exciting about Christianity. Up until then, I had been politically liberal and thought that Christians apart from my mom were a faceless mass of white-bread Moral Majority types who controlled the world. I wanted to be a rebel, and part of defining myself that was was to not be a Christian. Chesterton suggested to me that it was the other way around; Christians were the true rebels.

G.K.C. and Fairy Tales

“My first and last philosophy, that which I believe in with unbroken certainty, I learnt in the nursery. I generally learnt it from a nurse; that is, from the solemn and star-appointed priestess at once of democracy and tradition. The things that I believed most then, the things that I believe most now, are the things called fairy tales.” – “The Logic of Elfland” from Orthodoxy.

Chesterton was a lover of fairy tales. He read them. He wrote them. He wrote about them. He defended them.

And the lessons he learned about life did indeed seem to arise from them. For to him, they were the truest way to judge life.

“They seem to me to be the entirely reasonable things. They are not fantasies: compared with them other things are fantastic. Compared with them religion and rationalism are both abnormal, though religion is abnormally right and rationalism abnormally wrong.” (“Elfland”)

And people who do not respect fairy tales are missing the point. As he notes in “Fairy Tales” (from All Things Considered):

“SOME solemn and superficial people (for nearly all very superficial people are solemn) have declared that the fairy-tales are immoral; … The objection, however, is not only false, but very much the reverse of the facts. The fairy-tales are at root not only moral in the sense of being innocent, but moral in the sense of being didactic, moral in the sense of being moralizing.”

He also argued against those who thought children should not hear fairy tales because they might be frightened. He countered that fairy tales provide children with a sense that they can overcome fear.

“Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.” ("The Red Angel" from Tremendous Trifles.)

Not only do fairy tales teach the child that his fears and enemies can be overcome, they also teach him that the world has limits.

“If you really read the fairy-tales, you will observe that one idea runs from one end of them to the other - the idea that peace and happiness can only exist on some condition. This idea, which is the core of ethics, is the core of the nursery-tales. The whole happiness of fairyland hangs upon a thread, upon one thread.” ("Fairy Tales")

He makes a similar point in Orthodoxy.

“For the pleasure of pedantry I will call it the Doctrine of Conditional Joy. Touchstone talked of much virtue in an "if"; according to elfin ethics all virtue is in an "if." The note of the fairy utterance always is, "You may live in a palace of gold and sapphire, if you do not say the word `cow'"; or "You may live happily with the King's daughter, if you do not show her an onion." The vision always hangs upon a veto. All the dizzy and colossal things conceded depend upon one small thing withheld. All the wild and whirling things that are let loose depend upon one thing that is forbidden.”

He goes on to note: “Strike a glass, and it will not endure an instant; simply do not strike it, and it will endure a thousand years. Such, it seemed, was the joy of man, either in elfland or on earth; the happiness depended on NOT DOING SOMETHING which you could at any moment do and which, very often, it was not obvious why you

should not do.” (Orthodoxy).

Thus fairy tales, rather than being something to avoid or something trivial, teach children lessons – and can teach us all lessons.

“This is the profound morality of fairy-tales; which, so far from being lawless, go to the root of all law. Instead of finding (like common books of ethics) a rationalistic basis for each Commandment, they find the great mystical basis for all Commandments.” (“Fairy Tales”)

Indeed, they can help one’s faith to grow.

“Exactly what the fairy tale does is this: it accustoms him for a series of clear pictures to the idea that these limitless terrors had a limit, that these shapeless enemies have enemies in the knights of God, that there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear.” (“The Red Angel”).

So read fairy tales to your children. They may help them to sleep, to deal with life’s problems, and to get to heaven!

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

A Relatively Unknown Friend

Anyway, I ran across the following passage in one of Joseph Epstein's fabulous essays and thought it a good opportunity to give Baring a mention: "In one of the world's good books, Maurice Baring's The Puppet Show of Memory, Baring writes about the many good book in the pre-revolutionary summer home of his friend Count Benckendorff, and of a particular cupboard full of fine novels. 'Before going to bed, we would dive into that cupboard, and one was always sure, even in the dark, of finding something one could read.' This reminds me of friends who always put good books, both new and old, in their guest room, usually books suited to the guest's tastes. It is a lovely gesture of consideration, except that, when I have stayed with these friends, I am usually up half the night reading."

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

Orestes

Upon my return, I had a few leisure hours on Sunday to catch up on things cyber. During my surfing, I found a few interesting websites, like this one: The Orestes Brownson Council. It's a group at Notre Dame that is dedicated to discussing the classics of Catholic thought. Among the writers they study: "Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Orestes Brownson, John Henry Newman, Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, John Senior, G.K. Chesterton, St. Benedict, Evelyn Waugh, Hillaire [sic] Belloc and Christopher Dawson."

There are quite a few GKC friends in that assortment, plus a few that GKC would have befriended. I wish such an organization existed while I was at ND.

Bonus coverage: A book review I wrote for Gilbert Magazine about five years ago:

Orestes Brownson: Sign of Contradiction

Wilmington

(Hardcover, ISBN: 1 882926 33 1)

By R. A. Herrera

Chesterton, right?

This same man once walked into a room and heard a guy vilifying him for becoming a Catholic. After unsuccessfully warning him to curb his tongue, he grabbed the guy by the coat-collar and seat of his pants and threw him over a stovepipe.

Okay, it’s not Chesterton.

It’s Orestes Brownson, a man every bit as colorful as Chesterton but for different reasons.

In Orestes Brownson: Sign of Contradiction, R. A. Herrera provides a compact biography of Brownson’s life, his era, and his philosophical bent. In less than 140 pages, Herrera covers Brownson’s 1803 birth in

Perhaps most importantly, Herrera provides a broad overview of Brownson’s writings and a detailed assessment of them. This is no small task (indeed, after the initial 140 pages of text, Herrera adds forty more, largely devoted to a scholarly review of his writings). Brownson’s collected writings fill twenty thick volumes, and the writings don’t come in neatly-arranged books (of which Brownson wrote few). Brownson primarily wrote for Brownson’s Quarterly Review, a journal he published for over twenty years and for which he provided most of the script for each 20,000-plus word issue.

The surface similarities between Brownson and Chesterton, as already noted, are remarkable, but it’s difficult to imagine two men more different in their literary approach. In his writings, Brownson was always uncompromising, frequently slashing, and sometimes downright mean when dealing with his opponents. According to Herrera, Brownson had an “inclination to use a battle ax to crush a butterfly.” Another recent biographer wrote: “There is in Brownson’s style a rhetorical habit of using the harsh blow of a miner’s sledge when the tap of a carpenter’s hammer would be more effective.” Brownson made many enemies in his career as a writer and, though he was the intellectual gemstone of Catholic America, he was repeatedly a source of embarrassment as well. A man more distant than Chesterton can’t be imagined.

But if you dig yet deeper and get past the writings, similarities between the men crop up again. Brownson was a kind man, his made-for-public-consumption polemics notwithstanding. He was tenderly affectionate toward his wife and children and had many friends. He was deeply devoted to God; after his conversion, always writing with a crucifix in front of him and a statue of the Virgin Mary at his side.

He was also an untiring philosopher. All biographers have agreed that Brownson was an unflagging pursuer of truth. In his efforts, he mastered foreign languages and read volumes of the best thinkers in Western Civilization, from Plato to Kant, in their native tongues. Wherever the truth took him, he went.

His pursuit eventually took him into the Catholic Church, an extremely odd journey for an intellectual in nineteenth-century Protestant America. Catholicism was exotic. Brownson had never even seen a Catholic church until his early twenties and, true to the temperament of the age, gave Catholicism little thought. He was probably a little taken back when his friend, Daniel Webster, saw him idly glancing at some Catholic works in a used bookstore and warned him, “Take care how you examine the Catholic Church, unless you are willing to become a Catholic, for Catholic doctrines are logical.”

It is telling that, when he was already highly-Catholic in his ideas and writings, Brownson was totally unaware of it until a Catholic journal re-produced one of his articles. He was somewhat stunned as he suddenly realized that his studies and ideas had unwittingly brought him to the threshold of “Catholicity” (his word). After he realized this, he investigated the possibility of conversion, but got cold feet and delayed his entry for a year.

The reason for the delay? A very Chestertonian one and a reason that contributed to Chesterton’s prolonged delay: he didn’t want to ostracize or hurt his non-Catholic friends.

It’s not surprising and it illustrates the deepest layer of Brownson. Underneath Brownson’s intellectual pursuits, underlying the argumentative writings, stronger than his occasional flares of temper, ran a consistent theme: Love for his fellow men and a desire to see them happy and saved. And in this most important though often hidden trait, this large man was most like Chesterton.

Monday, July 03, 2006

Still more on the young Chestertonian front

This largely poetic blog is the province of a young woman named Sheila, a medievalist, iconoclast and devotee of Gilbert. The name of the blog is taken from a Greek term, most memorably used by our friend King Alfred, for a large tome he kept in which he kept note of sayings and citations that he found interesting or worthwhile.

The most notable recent content at Enchiridion is an open call for triolets, a wee form of poetry in the tradition of the Clerihew or the Haiku, as far as expansiveness goes. An example from Gilbert (from "Sociological Triolets") follows:

The Collectivist State

Is a prig and a bandit.

I despise and I hate

The Collectivist State;

It may be My Fate,

But I'm damned if I'll stand it!

The Collectivist State

Is a prig and a bandit.

So, in Sheila we have found a conglomeration of attributes that are all too rare in the blogosphere: Chesterton, medievalism, classical poetry, and femininity. Be sure to check her out.