Wednesday, March 29, 2006

One Born Every Decade

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Apologies

Wal-Mart

I suspect most of GKC's distributist children enjoyed the story about the student who lived at Wal-Mart for three days. If you didn't see it, here's a link.

I wrote a short story for Gilbert Magazine a few years ago that kind of anticipated this kid's antics. I electronically published it here, if you want to see it.

Friday, March 24, 2006

A spooky silence

Also, if it is not too bold, I would like to ask for support and prayers for Abdul Rahman, the Afgahni Christian now under threat of death for his "apostasy." Information about his infamous plight can be found here.

Though it is hoped that some amicable conclusion can be reached, the situation does not look good. In light of this, then, I hope the following is not felt to be inappropriate...

The Last Hero

G.K. Chesterton (1901)

The wind blew out from Bergen from the dawning to the day,

There was a wreck of trees and fall of towers a score of miles away,

And drifted like a livid leaf I go before its tide,

Spewed out of house and stable, beggared of flag and bride.

The heavens are bowed about my head, shouting like seraph wars,

With rains that might put out the sun and clean the sky of stars,

Rains like the fall of ruined seas from secret worlds above,

The roaring of the rains of God none but the lonely love.

Feast in my hall, O foemen, and eat and drink and drain,

You never loved the sun in heaven as I have loved the rain.

The chance of battle changes -- so may all battle be;

I stole my lady bride from them, they stole her back from me.

I rent her from her red-roofed hall, I rode and saw arise,

More lovely than the living flowers the hatred in her eyes.

She never loved me, never bent, never was less divine;

The sunset never loved me, the wind was never mine.

Was it all nothing that she stood imperial in duresse?

Silence itself made softer with the sweeping of her dress.

O you who drain the cup of life, O you who wear the crown,

You never loved a woman's smile as I have loved her frown.

The wind blew out from Bergen to the dawning of the day,

They ride and run with fifty spears to break and bar my way,

I shall not die alone, alone, but kin to all the powers,

As merry as the ancient sun and fighting like the flowers.

How white their steel, how bright their eyes! I love each laughing knave,

Cry high and bid him welcome to the banquet of the brave.

Yea, I will bless them as they bend and love them where they lie,

When on their skulls the sword I swing falls shattering from the sky.

The hour when death is like a light and blood is like a rose, --

You never loved your friends, my friends, as I shall love my foes.

Know you what earth shall lose to-night, what rich uncounted loans,

What heavy gold of tales untold you bury with my bones?

My loves in deep dim meadows, my ships that rode at ease,

Ruffling the purple plumage of strange and secret seas.

To see this fair earth as it is to me alone was given,

The blow that breaks my brow to-night shall break the dome of heaven.

The skies I saw, the trees I saw after no eyes shall see,

To-night I die the death of God; the stars shall die with me;

One sound shall sunder all the spears and break the trumpet's breath:

You never laughed in all your life as I shall laugh in death.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Chesterton in the SEP

Monday, March 20, 2006

Hard Times

By way of consolation (though 'tis not much), I've decided to share with you my personal favourite piece of Chestertonia, a short and epic story that should be read by any man, woman or child with an interest in anything.

How I found the Superman

G.K. Chesterton (1909)

Readers of Mr. Bernard Shaw and other modern writers may be interested to know that the Superman has been found. I found him; he lives in South Croydon. My success will be a great blow to Mr. Shaw, who has been following quite a false scent, and is now looking for the creature in Blackpool; and as for Mr. Wells's notion of generating him out of gases in a private laboratory, I always thought it doomed to failure. I assure Mr. Wells that the Superman at Croydon was born in the ordinary way, though he himself, of course, is anything but ordinary.Nor are his parents unworthy of the wonderful being whom they have given to the world. The name of Lady Hypatia Smythe-Brown (now Lady Hypatia Hagg) will never be forgotten in the East End, where she did such splendid social work. Her constant cry of "Save the children!" referred to the cruel neglect of children's eyesight involved in allowing them to play with crudely painted toys. She quoted unanswerable statistics to prove that children allowed to look at violet and vermillion often suffered from failing eyesight in their extreme old age; and it was owing to her ceaseless crusade that the pestilence of the Monkey-on-the-Stick was almost swept from Hoxton.

The devoted worker would tramp the streets untiringly, taking away the toys from all the poor children, who were often moved to tears by her kindness. Her good work was interrupted, partly by a new interest in the creed of Zoroaster, and partly by a savage blow from an umbrella. It was inflicted by a dissolute Irish apple-woman, who, on returning from some orgy to her ill-kept apartment, found Lady Hypatia in the bedroom taking down some oleograph, which, to say the least of it, could not really elevate the mind.

At this the ignorant and partly intoxicated Celt dealt the social reformer a severe blow, adding to it an absurd accusation of theft. The lady's exquisitely balanced mind received a shock; and it was during a short mental illness that she married Dr. Hagg.

The rest can be found here, courtesy of the excellent Martin Ward. And so, ye soft types, read on.

Friday, March 17, 2006

Chesterton on the Irish

THE average autochthonous Irishman is close to patriotism because he is close to the earth; he is close to domesticity because he is close to the earth; he is close to doctrinal theology and elaborate ritual because he is close to the earth. In short, he is close to the heavens because he is close to the earth.GKC in George Bernard Shaw

(as quoted in Chesterton Day by Day, 1912)

Belloc's Windlessmill

The largest and oldest working mill in Sussex is being prepared for a new season, and, later this year, it may not have to rely on the wind. Volunteers from the Friends of Shipley Mill are busy working to re-instate equipment in the engine shed so that they can demonstrate flour milling at every open day. "I am afraid we cannot always rely on the wind, and milling is always something that visitors like to see," explained David French, chairman of the Friends. Shipley Mill was built in 1879 and restored in 1990 as a memorial to the Sussex poet, historian and novelist Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953), who lived nearby and owned the mill for nearly 50 years.link to the article in the West Sussex County Times (Horsham)

Thursday, March 16, 2006

Those pictures, finally

Naughts & Crescents, by Martin Gardner

Like Gilbert Chesterton's The Ball and the Cross, The Flying Inn is a comic fantasy almost totally forgotten today, even by Chestertonians. In view of the current explosion of Islamic fundamentalism, and the rise of terrorism against infidel nations, The Flying Inn has an eerie relevance to the Iraq war that keeps the novel from flying into complete obscurity.You can read all of "Naughts & Crescents" by Martin Gardner at The New Criterion; but you will need to subscribe or purchase the individual article to do so. (More than I have excerpted above is freely available at their website. So click to whet your appetite.)

Lord Phillip Ivywood, the novel's main character, is England's handsome, golden-voiced Prime Minister. He has come under the influence of a Turkish fanatic, Misyara Ammon, a large-nosed, black-bearded Muslim popularly known as the Prophet of the Moon. He has convinced Lord Ivywood that the Muslim faith is superior to Christianity. It is a progressive force destined to dominate the world. Ivywood has decided that Christianity and Islam should merge, with the Muslim crescent placed alongside the cross on top of London's St. Paul's Cathedral. Better yet, the cross should be abandoned for a new symbol that combines cross and crescent, perhaps called the "crosslam."

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

GKC and the Sandman

G.K. Chesterton was a leading character, and a surprisingly true-to-life one, in DC's award-winning comic book, The Sandman, numbers 10 through 16 (November, 1989—June, 1990). The character returned to The Sandman in issue 39 (July, 1992); and showed again for brief third and a fourth turns in numbers 63 and 65 (September and December, 1994). The Gilbert character's later appearances were brief, unexciting, and devoid of apparent significance. The third ended with his violent, grisly, unfunny comic-book death. Gilbert's final appearance came in the August, 1995 issue, as he indignantly refused to permit Morpheus (the Sandman) to raise him from the dead! DC Comics ended publication of The Sandman with issue number 75.

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

New Gilbert

It's not too surprising, though. Technorati says half of all new blogs are defunct within three months after their inaugural post.

I hope to feature GKC blogs in a future column I'm working on. Let's hope they don't all die before I get a chance.

Two poems

Ballade of Kindness to Motorists

O Motorists, Motorists, run away and play,

I pardon you. Such exercise resigned,

When would a statesman see the woods in May?

How could a banker woo the western wind?

When you have knocked a dog down I have pined,

When you have kicked the dust up I have sneezed,

These things come from your absence - well, of Mind -

But when you get a puncture I am pleased.

I love to see you sweating there all day

About some beastly hole you cannot find;

While your poor tenants pass you in a dray,

Or your sad clerks bike by you at grind,

I am not really cruel or unkind;

I would not wish you mortally diseased,

Or deaf or dumb or dead or mad or blind,

But when you get a puncture I am pleased.

What slave that dare not smile when chairs give way?

When smart boots slip, having been lately shined?

When curates cannon with the coffee tray?

When trolleys take policemen from behind?

When kings come forth in public, having dined,

And palace steps are just a trifle greased? -

The joke may not be morbidly refined,

But when you get a puncture I am pleased.

Prince of the Car of Progress Undefined!

On to your far Perfections unappeased!

Leave your dead past with its dead children lined;

But when you get a puncture I am pleased.

The Jazz

A Study of Modern Dancing, in the manner of Modern Poetry

Tlanngershshsh!

Thrills of vibrant discord,

Like the shivering of glass;

Some people dislike it; but I do not dislike it.

I think it is fun,

Approximating to the fun

Of merely smashing a window;

But I am told that it proceeds

From a musical instrument,

Or at any rate

From an instrument.

Black flashes . . .

. . . Flashes of intermitten darkness;

Somebody seems to be playing with the electric light;

Some may possibly believe that modern dancing

Looks best in the dark.

I do not agree with them.

I have heard that modern dancing is barbaric,

Pagan, shameless, shocking, abominable.

No such luck - I mean no such thing.

The dancers are singularly respectable

To the point of rigidity,

With something of the rotatory perseverence

Of a monkey on a stick;

But there is more stick than monkey,

And not, as slanderers assert,

More monkey than stick.

Let us be moderate,

There are a lot of jolly people doing it,

(Whatever it is),

Patches of joyful colour shift sharply,

Like a kaleidoscope.

Green and gold and purple and splashes of splendid black,

Familiar faces and unfamiliar clothes;

I see a nice-looking girl, a neighbour of mine, dancing.

After all,

She is not very different;

She looks nearly as pretty as when she is not dancing . . .

. . . I see certain others, less known to me, also dancing.

They do not look very much uglier

Than when they are sitting still.

(Bound, O Terpsichore, upon the mountains,

With all your nymphs upon the mountains,

And Salome that held the heart of a king

And the head of a prophet;

For to the height of this tribute

Your Art has come.)

If I were writing an essay

- And you can put chunks of any number of essays

Into this sort of poem -

I should say that there was a slight disproportion

Between the music and the dancing;

For only the musician dances

With excitement,

While the dancers remain cold

And relatively motionless

(Orpheus of the Lyre of Life

Leading the forests in fantastic capers;

Here is your Art eclipsed and reversed,

For I see men as trees walking).

If Mr. King stood on his head,

Or Mr. Simon butted Mr. Gray

In the waistcoat,

Or the two Burnett-Browns

Strangled each other in their coat-tails,

There would then be a serene harmony,

A calm unity and oneness

In the two arts.

But Mr. King remains on his feet,

And the coat-tails of Mr. Burnett-Brown

Continue in their customary position.

And something else was running in my head -

- Songs I had heard eariler in the evening;

Songs of true lovers and tavern friends,

Decent drunkenness with a chorus,

And the laughter of men who could riot.

And something stirred in me;

A tradition

Strayed from an older time,

And from the freedom of my fathers:

That when there is banging, yelling and smashing to be done,

I like to do it myself,

And not delegate it to a slave,

However accomplished.

And that I should sympathise,

As with a revolt of human dignity,

If the musician had suddenly stopped playing,

And had merely quoted the last line

Of a song sung by Mrs. Harcourt Williams:

"If you want any more, you must sing it yourselves."

==

Such scathing rebukes! How did he do it! More, of course, as time goes by.

Monday, March 13, 2006

Alas

I will take this opportunity, anyhow, to wish C&F contributor Eric Scheske a happy birthday. Our illustrious patriarch turns forty today, and he feels every year of it. Here's to forty more, Eric, before you slow your pace!

Friday, March 10, 2006

A Very Condensed Narnia

Once there were four children, Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy, who were sent from London during the war to live in the country house of an old Professor and his housekeeper, Mrs. Macready. She was not fond of children, and he was a very old man with shaggy white hair, which grew over most of his face as well as on his head.continue reading...

“This house is so big that no one will mind what we do,” said Peter. “Let’s explore tomorrow.”

Everyone agreed to this, and that was how the adventure began. The first few doors the children tried led to spare bedrooms. Then came a long room full of pictures and a suit of armor; and after that, three steps down and five steps up, a whole series of rooms lined with books, some bigger than a Bible, and lastly, a room that was empty except for one big wardrobe with a mirror in the door.

“Nothing there!” said Peter, and they all trooped out again—except Lucy. She looked inside the wardrobe and saw several fur coats hanging up. She got in among them and kept her arms stretched out in front of her in order to not bump into the back of the wardrobe. This must be enormous! thought Lucy, stepping in further.

She felt something soft and powdery under her feet, and tree branches rubbed against her face. Then she saw a light. In a moment she was standing in the middle of a wood at night with snowflakes falling through the air.

And soon after that, a Faun stepped out from the trees. From the waist up he was like a man, but his legs were shaped like a goat’s, and he had a tail neatly caught up over one arm that also held an umbrella.

“Are you a Daughter of Eve—Human?” he asked.

Pakistanis for Chesterton

C.S. Lewis On Stage

A desk, a chair and a podium are all that [Tom] Key needed to put the audience of about 200 in the presence of Lewis, a prolific and wildly witty author who also penned his autobiography, "Surprised by Joy," published in 1955.link to entire article, "Actor re-creates C.S. Lewis in one-man show" in the South Bend Tribune

The show, with plenty of laughs, demonstrates Lewis' contention that longing is joy and happiness. Our constant search for God, even in everyday, humdrum life, is the ultimate joy.

During the show, "Surprised by Joy" serves as a tool for narration and advancement, while Key takes side trips into Lewis' other works including "The Great Divorce," "Mere Christianity," "The Problem of Pain" and "The Screwtape Letters" as well as his poetry.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

A Cautionary Tale ("Susan, Who Crossed the Tracks Without Watching, and Was Sucked Under a Train and Hurled Against a Lamp Post")

The children have had chickenpox this week - a ghastly sight (and sound), made worse by their constant demands to be entertained. There is one story in particular they never tire of hearing - about a handsome bull in a field, and how he gored one of their cousins.link to the full article, Day of the Dad: Gory Stories

I'd like to say that it was a case of the outer ugliness of their condition poisoning their inner purity, but their enthusiasm for the Hilaire Belloc-ish tale of Constantin, who climbed a farm gate with disastrous consequences, is nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, it's about time they dug up their other gruesome favourite - the cheery tale, related to us by a nice old man in a little town near New Orleans, of how a local strawberry seller got sucked under a goods train after crossing the tracks to her car at the wrong moment.

I can't remember all the details - I think the body ended up being hurled against a lamp post - but I guarantee that our son does, and encourages us to share them with almost everyone we meet.

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

Crunchy GKC

Link.

Link.

By the way, I applaud NR's embrace of Crunchy Cons. The name "Crunchy Con" grates (crunches) on me, but its principles and ideas are deeply Chestertonian. The blog is worth watching.

Rowling a Friend?

"She is a member of the Church of Scotland (the Scottish Anglican Church-- not the Presbyterian church). She refuses to reveal more of her Christian faith than that because, she says, it would give away too much of book 7 (to me that is very intriguing). Her favorite poem is "The Boy Who Ran Away From His Nurse and got Eaten by a Lion," by Hilaire Belloc. She also is a member of the English Chesterton Society. She is educated in both Latin and Greek and is well versed in the canon of classic Western literature. Besides Chesterton and Belloc, some of her favorite authors are Dickens and Jane Austen."

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

The Square Club

Monday, March 06, 2006

The Coloured Lands - Self Deprecation

Today, instead, we will observe six pieces of self-deprecating and witty cartoonery that can be found in The Coloured Lands. They are by no means the only examples of such that can be found in the book, of course. I have refrained from scanning the others for now, as the American Chesterton Society already has 'em. The first seven images there are from The Coloured Lands, and are quite delightful. My favourite of them is "Mrs. Chesterton's Donkeys in Waiting."

Some of these pictures have text, naturally, so will provide a brief transcript when necessary.

-Little Bo-Peep-

-Little Bo-Peep- -A True Victorian cuts a disreputable Author-

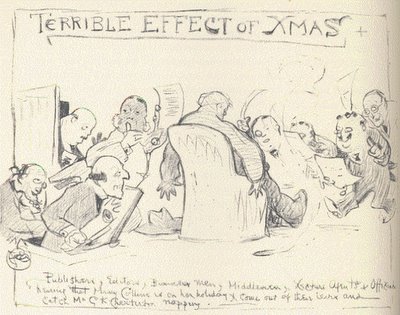

-A True Victorian cuts a disreputable Author- -Terrible Effect of XMas-

-Terrible Effect of XMas-Publishers, Editors, Business Men, Middlemen, Lecture Agents and Officials, hearing that Mary Collins is on her holiday, come out of their lairs and catch Mr. G.K. Chesterton napping.

Publishers, Creditors, Interviewers, Cranks, Etc. - fleeing before the Perfect Secretary.

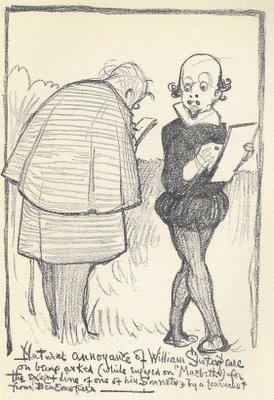

Publishers, Creditors, Interviewers, Cranks, Etc. - fleeing before the Perfect Secretary. Natural annoyance of William Shakespeare on being asked (while engaged on Macbeth) for the exact line of one of his Sonnets by a journalist from Beaconsfield.

Natural annoyance of William Shakespeare on being asked (while engaged on Macbeth) for the exact line of one of his Sonnets by a journalist from Beaconsfield. -Just Indignation of Queen Victoria-

-Just Indignation of Queen Victoria-That's all for this installment. Perhaps something more midweek, like last time, to lift our spirits. I'll have a bit of time to kill in the afternoon on Wednesday, as it happens.

Friday, March 03, 2006

Pimping TDVC With GKC

TDVC is neither "good bad" literature nor is it "bad good" literature -- it is "bad bad". It is the addict's heroin.

Stephen Bayley's worst sin was pimping TDVC by summoning Uncle Gilbert: "The good bad critical label can be traced to G.K. Chesterton, inspired by the extraordinary number of very bad books, ripe with imperial pomp, scintillating with sexually repressed jingoism, that were published in the Edwardian era. But boorish pulp can be enjoyable. Bad can be good."

But wrong can never be right.

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Schall on Belloc for Lent

For Lent, I will read Hilaire Belloc's Places. Belloc is the best essayist in our language. Here are essays on places from North to the South of Europe, to the Mideast, to North Africa. The memory of what we are, or perhaps of what we were and are now rejecting, is here found. The third essay is "On Wandering;" the final essay is "About Wine," neither to be missed. I heard of a new book that, like the European constitutionalists, wrote of Europe as if it had no Christian roots. But, "A (man) travels in order to visit cities and men, and to get a knowledge of the real places where things happened in the past, getting a knowledge also of how the mind of man worked in building and works now in daily life." Today we must also find these same places in books, lest we forget what we are.read all the responses at NRO's The Lenten Bookshelf

— Father James V. Schall, S. J., is a professor of government at Georgetown University. He is author of, among other books, Another Sort of Learning.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

The Coloured Lands - A Request

Homesick at Home

By G.K. Chesterton

One, seeming to be a traveller, came to me and said, "What is the shortest journey from one place to the same place?"

The sun was behind his head, so that his face was illegible.

"Surely," I said, "to stand still."

"That is no journey at all," he replied. "The shortest journey from one place to the same place is round the world." And he was gone.

White Wynd had been born, brought up, married and made the father of a family in the White Farmhouse by the river. The river enclosed it on three sides like a castle: on the fourth side there were stables and beyond that a kitchen-garden and beyond that an orchard and beyond that a low wall and beyond that a road and beyond that a pinewood and beyond that a cornfield and beyond that slopes meeting the sky, and beyond that - but we must not catalogue the whole earth, though it is a great temptation. White Wynd had known no other home but this. Its walls were the world to him and its roof the sky.

This is what makes his action so strange.

In his later years he hardly ever went outside the door. And as he grew lazy he grew restless: angry with himself and everyone. He found himself in some strange way weary of every moment and hungry for the next.

His heart had grown stale and bitter towards the wife and children whom he saw every day, though they were five of the good faces of the earth. He remembered, in glimpses, the days of his toil and strife for bread, when, as he came home in the evening, the thatch of his home burned with gold as though angels were standing there. But he remembered it as one remembers a dream.

Now he seemed to be able to see other homes, but not his own. That was merely a house. Prose had got hold of him: the sealing of the eyes and the closing of the ears.

At last something occurred in his heart: a volcano; an earthquake; an eclipse; a daybreak; a deluge; an apocalypse. We might pile up colossal words, but we should never reach it. Eight hundred times the white daylight had broken across the bare kitchen as the little family sat at breakfast. And the eight hundred and first time the father paused with the cup he was passing in his hand.

"That green cornfield through the window," he said dreamily, "shining in the sun. Somehow, somehow it reminds me of a field outside my own home."

"Your own home?" cried his wife. "This is your home."

White Wynd rose to his feet, seeming to fill the room. He stretched forth his hand and took a staff. He stretched it forth again and took a hat. The dust came in clouds from both of them.

"Father," cried one child. "Where are you going?"

"Home," he replied.

"What can you mean? This is your home. What home are you going to?"

"To the White Farmhouse by the river."

"This is it."

He was looking at them very tranquilly when his eldest daughter caught sight of his face.

"Oh, he is mad!" she screamed, and buried her face in her hands.

He spoke calmly. "You are a little like my eldest daughter," he said. "But you haven't got the look, no, not the look which is a welcome after work."

"Madam," he said, turning to his thunderstruck wife with a stately courtesy. "I thank you for your hospitality, but indeed I fear I have trespassed on it too long. And my home--"

"Father, father, answer me! Is not this your home?"

The old man waved his stick.

"The rafters are cobwebbed, the walls are rain-stained. The doors bind me, the rafters crush me. There are littlenesses and bickerings and heartburnings here behind the dusty lattices where I have dozed too long. But the fire roars and the door stands open. There is bread and raiment, fire and water and all the crafts and mysteries of love. There is rest for heavy feet on the matted floor, and for starved heart in the pure faces, far away at the end of the world, in the house were I was born."

"Where, where?"

"In the White Farmhouse by the river."

And he passed out of the front door, the sun shining on his face.

And the other inhabitants of the White Farmhouse stood staring at each other.

White Wynd was standing on the timber bridge across the river, with the world at his feet. And a great wind came flying from the opposite edge of the sky (a land of marvellous pale golds) and met him. Some may know that that first wind outside the door is to a man. To this man it seemed that God had bent back his head by the hair and kissed him on the forehead.

He had been weary with resting, without knowing that the whole remedy lay in sun and wind and his own body. Now he half believed that he wore the seven-leagued boots.

He was going home. The White Farmhouse was behind every wood and beyond every mountain wall. He looked for it as we all look for fairyland, at every turn of the road. Only in one direction he never looked for it, and that was where, only a thousand yards behind him, the White Farmhouse stood up, gleaming with thatch and whitewash against the gusty blue of morning.

He looked at the dandelions and crickets and realised that he was gigantic. We are too fond of reckoning always by mountains. Every object is infinitely vast as well as infinitely small. He stretched himself like one crucified in an uncontainable greatness.

"Oh God, who has made me and all things, hear four songs of praise. One for my feet that Thou hast made strong and light upon Thy daisies. One for my head, which Thou hast lifted and crowned above the four corners of Thy heaven. One for my heart, which Thou hast made a heaven of angels singing Thy glory. And one for that pearl-tinted cloudlet far away above the stone pines on the hill."

He felt like Adam newly created. He had suddenly inherited all things, even this suns and stars.

Have you ever been out for a walk?

* * * * *

The story of the journey of White Wynd would be an epic. He was swallowed up in huge cities and forgotten: yet he came out on the other side. He worked in quarries, and in docks in country after country. Like a transmigrating soul, he lived a series of existences: a knot of vagabonds, a colony of workmen, a crew of sailors, a group of fishermen, each counted him a final fact in their lives, the great spare man with eyes like two stars, the stars of ancient purpose.

But he never diverged from the line that girdles the globe.

On a mellow summer evening, however, he came upon the strangest thing in all his travels. He was plodding up a great dim down, that hid everything, like the dome of the earth itself. Suddenly, a strange feeling came over him. He glanced back at the waste of turf to see if there was any trace or boundary, for he felt like one who has just crossed the border of elfland. With his head a belfry of new passions, assailed with confounding memories, he toiled on the brow of the slope.

The setting sun was raying out a universal glory. Between him and it, lying low on the fields, there was what seemed to his swimming eyes a white cloud. No, it was a marble palace. No, it was the White Farmhouse by the river.

He had come to the end of the world. Every spot on earth is either the beginning or the end, according to the heart of man. That is the advantage of living on an oblate spheroid.

It was evening. The whole swell of turf on which he stood was turned to gold. He seemed standing in fire instead of grass. He stood so still that the birds settled on his staff.

All the earth and the glory of it seemed to rejoice around the madman's homecoming. The birds on their way to their nests knew him, Nature herself was in his secret, the man who had gone from place to the same place.

But he leaned wearily on his staff. Then he raised his voice once more.

"O God, who hast made me and all things, hear four songs of praise. One for my feet, because they are sore and slow, now that they draw near the door. One for my head, because it is bowed and hoary, now that Thou crownest it with the sun. One for my heart, because Thou hast taught it in sorrow and hope deferred that it is the road that makes the home. And one for that daisy at my feet."

He came down over the hillside and into the pinewood. Through the trees he could see the red and gold sunset settling down among the white farm-buildings and the green apple-branches. It was his home now. But it could not be his home till he had gone out from it and returned to it. Now he was the Prodigal Son.

He came out of the pinewood and across the road. He surmounted the low wall and tramped through the orchard, through the kitchen garden, past the cattle-sheds. And in the stony courtyard he saw his wife drawing water.

==

That's it. Some of you may recall a piece of poetry of Chesterton's called "On the Disastrous Spread of Aestheticism in All Classes," a selection from which follows:

The babe upraised his wondering eyes,

And timidly he said,

"A trend towards experiment

In modern minds is bred.

"I feel the will to roam, to learn

By test, experience, nous,

That fire is hot and ocean deep,

And wolves carnivorous.

"My brain demands complexity,"

The lisping cherub cried.

I looked at him, and only said,

"Go on. The world is wide."

A tear rolled down his pinafore,

"Yet from my life must pass

The simple love of sun and moon,

The old games in the grass;

"Now that my back is to my home

Could these again be found?"

I looked on him and only said,

"Go on. The world is round."

GKC on Ash Wednesday

"G. K.Chesterton said, 'Let your religion be less a theory and more of a love affair.' Chesterton reminds us that true religion is a passion for God. At stake in this is the fact that the things we are called to do in Lent are not meant to change the world; they are first meant to change us."

Link.